A WWII Romance: Horace Greasly

By Bianca Ozeri

Horace Greasly was born on Christmas. Into a world plastered still by snow, that kept families indoors, huddled over fires. The year was 1918, and the place was Ibstock, Leicestershire, a farming village in the English Midlands where the Belvoir Castle stood on the distant crest of a rolling hill. Born into the arms of a mother called Mabel. Born into romance.

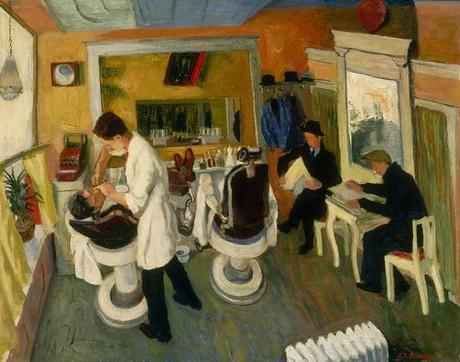

Nicknamed Jim, Horace was the town barber. He kept hair out of the faces of locals and a few days before he left, at the behest of the draft, Jim was cutting the right hair. That of a man responsible for the next intake of firemen in Ibstock. Firefighting was a reserved profession during the war and meant exception from the draft. The client, a rotund man, offered Jim the job with a wink and a nod.

And Jim went to war instead. After just seven weeks of training with the 2nd/5th Battalion Leicesters, he went to battle against the might of an ethnocentric nation. With just thirty rounds of ammunition strapped across a boy’s heart.

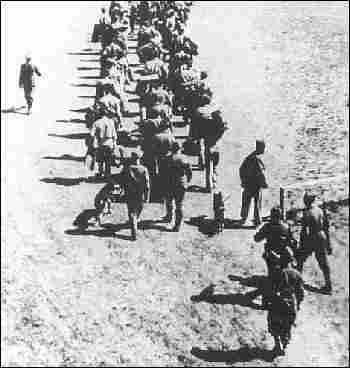

Jim’s soldiership fell prey to captivity however, when on May 25th, 1940, the twenty-year old was taken Prisoner of War. En route to Holland, comrades beside him and enemies before him, Jim endured a ten week march. Food was scarce, and many men, fallen to exhaustion on the side of the road, received a bullet in the back of the head — a savior for some, I imagine. Jim survived on dandelion leaves, small insects, and parcels of food offered by sympathetic villagers. Rain water was drank out of ditches in the road, and Jim just barely made it.

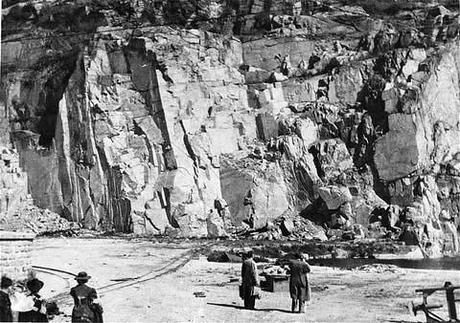

A three day journey from Holland to Polish Silesia, then annexed as part of Germany, landed Jim in the country’s second PoW camp, attached, at the south end, to a granite quarry. I imagine the vast ravine of stone in grays was one of two things to prisoners: a daily reminder of German potential, or the last vestiges of any visible beauty. For Jim, it must have been the latter, for he fell in love with the director’s daughter.

Rosa was seventeen, living outside the camp and working as an interpreter for the Germans. The two, with the emaciated bodies and marred spirits of war, were drawn to one another instantly.

A clandestine romance, theirs was one lived on secret trysts and handwritten notes. Lovemaking in muddy corners of a barbed wire fence beneath an unpolluted sky. One that, somehow, survived the light of day, when the watchful German eye felt omniscient.

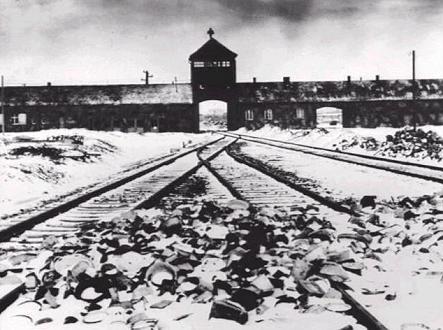

At the end of 1940 though, Jim was transferred to Freiwaldau, an annex of Auschwitz, some forty miles from Rosa. The lovers’ separation lacked a farewell, and continuing the affair seemed possible only in the dream of a very good sleep.

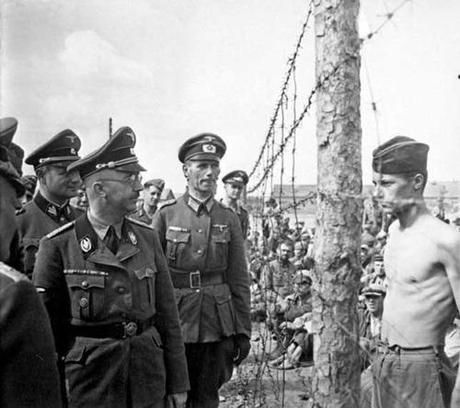

(A gaunt Greasley demands more rations for prisoners, unaware he was demanding them from Heinrich Himmler.)

Letters were exchanged via members of outside work parties, who would often come to Jim for a haircut. They wouldn’t suffice though — letters and dreams. Rosa, it seems, would be the only thing…

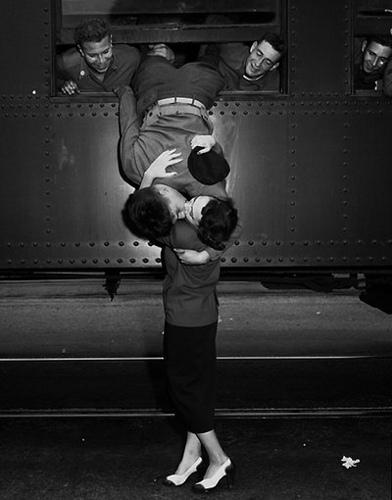

(I regret to inform that this lovely lady is not Rosa. It seems there are no accessible photos of Horace’s beloved. A detail, I think, makes the story even more ethereal.)

And so, in an otherworldly devotion to love, the barber escaped from his camp almost four nights a week to meet his lady, who, often assigned to interpretation around Auschwitz, lingered on the outskirts of the dastardly camp, waiting for the consolation of love. The arrival of whom could never be certain.

But certain it ended up being, for the over two hundred times that Horace leaked out of that fence, only to return to captivity, every night, under the cover of a darkness, which seemed to postpone twilight just for him.

It’s no radical idea that hardship has a way of splintering one’s shield. It is in fact, probably, the oldest, the most clichéd. In the black abyss of cruelty, love shows itself in its purest form, in the same way shapes become illuminated when you shut your eyes tight, for very long.

I often find myself in the throes of a cruel, apocalyptic daydream — an interwoven thread of romance my most visited plot line. And I emerge from them, only to remember, that this race is not innocent of monstrous savagery, but nor, in those times, bereft of our addiction to love.