Chicken eggs are one of the world's most popular foods, and have a significant presence in the diet of both Italians and North Americans. The eggs themselves and the way they are consumed, however, are substantially different between Italy and North America. In this article, I will list 5 fundamental differences. I will also describe why eggs are an essential ingredient in cooking, and a marvel of nutrition.

Color and nutritional/culinary properties

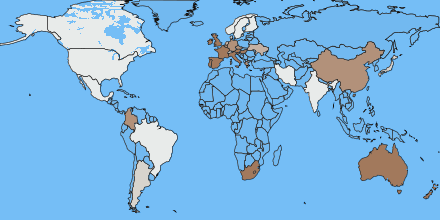

The first most obvious difference is in the color of the shell. In Italy eggs are prevalently brown; in North America, prevalently white (difference #1). The shell color comes from the breed of the chicken: white hens make white eggs, red and brown hens make brown eggs. Italian chickens, however, are not indigenously brown – their breed is chosen by the breeders according to the preference of the market. It's interesting to see it how such preference varies around the world. As illustrated in the map below, the shell color doesn't have any obvious correlation to the geographical location - it varies more based on culture.

Distribution of white eggs versus brown eggs

as reported by the International Egg Commission in 2008.

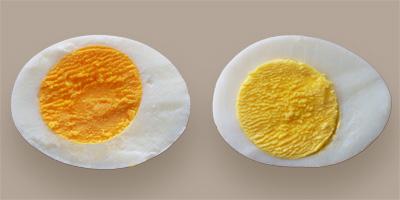

The color of the yolk depends instead on the hen's diet. If the hen is fed plants rich in xanthophylls (such as alfalfa or yellow corn), the yolk acquires a darker color. As with the shell, though, the choice of the feed is driven by the customers: North America prefers lemony-gold yolks, whereas Italy and most of Europe prefer dark yellow and deep orange yolks.

A dark yellow yolk found in a brown egg,

and a lemony yellow yolk found in a white egg.

Nutritionally speaking, brown eggs are identical to white eggs. Both are designed to nourish the embryo until the chick hatches after 21 days of incubation.

Within the egg, the yolk and the white have substantially different properties. The yolk weights about 1/3rd of the whole egg, and contains ¾ of its calories in the form of proteins and aggregates of proteins-fat-lechitin. These aggregates are what give eggs their emulsifying properties: the amazing capacity to bind with both fat and water to create wonders like mayonnaise and Hollandaise sauce.

The egg's white (or albumen) contains a similar amount of protein as the yolk, but the majority of those proteins actually have anti-nutritional value. While they are nourishing for the embryo, they inhibit digestive enzymes and prevent the absorption of vitamins and iron (note: these effects are neutralized when the albumen is cooked). The egg white also contains ovomucin, a protein with thickening and binding properties meant to protect the developing bird. Ovomucin is also very valuable in cooking: it helps keep together cakes and certain kinds of pasta (e.g. tagliatelle and lasagna), stabilize egg foam, and give a shiny finish to pastries.

Salmonella

Eating raw eggs is discouraged in North America. This isn't because of the anti-nutritional properties of egg white, but because of the fear of Salmonella, a bacterial infection that can have serious health consequences.

An egg in the UK, with its British Lion mark.

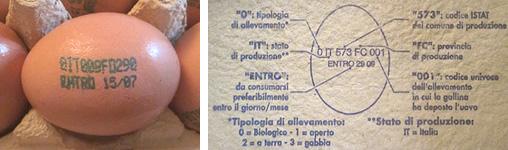

Both Europe and North America have been exposed to Salmonella outbreaks, but they have adopted different strategies to counteract them. In 1998, the UK introduced a program called the "British Lion Code of Practice". The program certifies egg farms that adhere to a stringent code of practice, which includes: vaccination for the hens, complete traceability of the hens' origins, and complete traceability of their feed. It also mandates that each egg be individually marked with a code identifying the expiry date, the farm of origin, and the keeping of the hens (free range, barn, or cage).

Since 2004, egg marking has been extended to the entire European Union.

An egg in Italy. On the eggs' carton, a legend explains on how to read the mark.

Despite overall improvements in the conditions in which hens are kept, North America still hasn't adopted the same stringent regulations. Salmonella infections are still quite common – in 2010 a major outbreak caused half a billion eggs to be recalled. As a result, North Americans are wary of raw eggs and the US FDA strongly recommends cooking eggs through, or using pasteurized eggs. In Italy and in the rest of Europe such fear is much less prevalent (difference #2). Raw eggs are also traditionally part of popular preparations, such as homemade mayonnaise and Tiramisu, so they are much less demonized.

Refrigeration

The fear of Salmonella is what also causes the next difference (difference #3). By law, in the USA and Canada eggs must be refrigerated in supermarkets and grocery stores. This policy is motivated by the fact that a contaminated egg can pose a threat only if the bacteria have a chance to multiply and completely colonize the egg, a process that is much slower at low temperatures.

Italy, the UK, and other parts of Europe don't have mandatory refrigeration. As a matter of fact they have the opposite policy: refrigeration is forbidden until the eggs reach their final storage destination (e.g. the home fridge). The reason for the different policy lies in another important difference: in Italy eggs are unwashed! (difference #4) When eggs are laid, they are covered with a thin natural film that makes the shell less porous and isolates it from bacteria that are present in the hen's intestinal tract. This film helps preserve the egg by maintaining more of its water content, by avoiding CO2 perspiration (a byproduct of the loss of acidity that occurs when the egg ages), and by isolating the egg from off-flavors that it could absorb from the environment (e.g. the smell of other foods in the fridge). This protective film can easily be washed away by the natural condensation of the moisture in the air as it comes into contact with the cold surface of a refrigerated egg. Condensation is particularly bad because it won't just wash off the protective film, it will actually melt it in place and allow any bacteria that is present on the surface of the egg to get inside. It's customary for Italians to wash eggs before using them, in case the shell comes in touch with the egg during cracking.

Uses

Despite the differences in the hens' breed and feed, eggs taste the same in Italy as they do in North America. However, traditionally, their role in the diet differs substantially. In Italy, eggs can be found, in various preparations, as lunch or dinner options; in North America they are mostly associated with breakfast (difference #5).

The names of the different cooking styles have creative translations in Italian:

- Sunny-side up → 'occhio di bue' (literally "bull's eye").

- Scrambled eggs → 'uova strapazzate' (literally "overworked" eggs).

- Hardboiled egg → 'uovo sodo' (literally "firm" egg).

- Soft boiled → 'alla coque' (from the French word for "shell").

- Poached → 'in camicia' (literally "in a shirt").

As described in the article "Breakfast or Colazione?", Italians prefer to start their day with something baked, along with coffee or cappuccino. Fried eggs are seen as an informal meal, often prepared in a frittata. In Italy, the word "frittata" (from 'fritto', fried) generically indicates a dish in which eggs are cooked in a pan on a layer of fat (butter, oil, or a mix of the two). To prepare a frittata, the eggs are beaten with salt and pepper, and sometimes a small amount of milk or water. Often, additional ingredients are mixed in, either individually or in combination. Common add-ons include vegetables (e.g. onions, mushrooms, zucchini, asparagus – all sautéed in advance), cheese (e.g. Provolone, Taleggio, swiss, Brie, grated Parmesan), and meat (prosciutto cotto – the Italian ham -, salame, sausage). In a frittata the eggs can either be scrambled or set. When set, the thickness can vary between a few millimeters (like in a French omelet), and a few centimeters (like in a Spanish omelet).

Other than in frittata, eggs are the main component of a number of other Italian dishes:

- Spaghetti alla Carbonara, a dish from the Rome region, as the main component of the sauce.

- Asparagi alla Milanese, sunny-side up, fried in butter.

- Sandwiches (e.g. as a zucchini Frittata).

- Stracciatella soup (also a dish from central Italy, known as "egg drop soup" in North America).

- The Tiramisu dessert (where raw eggs are part of the mascarpone cream).

- Pastry cream ('crema pasticcera') a custard used also to fill some kind of pasticcini.

- Zabaione, a dessert consisting in a light custard, flavored with Marsala wine.

- Gelato (as a natural emulsifier).

- 'Uovo sbattuto' an old-fashion afternoon snack (raw yolks beaten with sugar, with optional cocoa or even with a shot of espresso!)

The following instead are uses that are almost exclusively North American:

- As breakfast (any style with bacon or sausage, in breakfast bagels, breakfast burritos, Eggs Benedict).

- In the Egg Salad sandwich.

Finally, these are uses that are common between North America and Italy:

- To make 'Cotoletta alla Milanese', breaded veal, beef or pork steak – the Italian Schnitzel.

- In salads (hardboiled).

- In Deviled Eggs, or in its Italian equivalent (usually stuffed with tuna).

- In meringues (although Italian meringues are dry, light and crunchy, as opposed to soft and gooey).

- In preparations like cakes, egg pasta, and as an emulsifying and binding element in countless other recipes.