"What makes a city?" That is a question asked on IBM's Smarter City website. The company believes that a city is "an interconnected system of systems" that rests on three pillars: infrastructure, operations, and people. The site goes on to state that a city is "a dynamic work in progress, with progress as its watchword. A tripod that relies on strong support for and among each of its pillars, to become a smarter city for all." That definition may be a bit too cheery for some because they know that for years many inner cities have not progressed but languished or deteriorated. That entropic trend must change, because the world is becoming more urbanized every day. If tomorrow's cities are not going to become vast areas of poverty and decay, we have to be smarter about how they are planned, managed, and maintained. In a special issue about smart cities, the editors of Scientific American wrote:

"Many otherwise lucid thinkers, from Thomas Jefferson to Frank Lloyd Wright to President Gerald Ford, tended to think of cities as centers of poverty, crime, pollution, congestion and poor health. In recent years, though, the thinking has shifted along with the demographics. Many experts have come to realize that people are better off when they live in a city. This is not to dismiss the problems of urban life; cities, particularly fast-growing ones in the poorer parts of Asia and Africa, can be places of great human suffering. But even a city slum has benefits that you won't find on the farm or in the village. The move from the country leads, for instance, to dramatic changes for many women. As Kavita N. Ramdas of the Global Fund for Women notes in Stewart Brand's Whole Earth Discipline (Penguin, 2010), 'In the village, all there is for a woman is to obey her husband and relatives, pound millet, and sing. If she moves to town, she can get a job, start a business, and get education for her children.' Indeed, the city has come to look less like a source of problems than as an opportunity to fix them. Investments in sanitation and water have turned many cities in the developed world from places of disease and pestilence into bastions of health. City folk are at lower risk of death from motor vehicle accidents and suicide by firearms (although they are overstressed). From the standpoint of the metropolis, climate change also seems less intractable. Because city residents rely less on cars and live in more compact dwellings than suburbanites, they tend to leave smaller carbon footprints. The challenge is to extend the efficiency of the urban center to the wider conurbation, embracing the city center, suburbs and satellite towns. Although climate is bigger than any one fix, how we build our cities, and how efficiently we live in them, is going to factor large in our response." ["Street-Savvy," 17 April 2011]

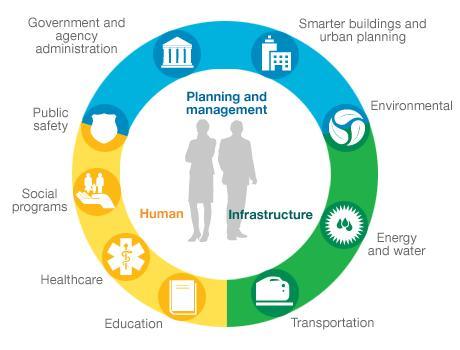

In Part 1 of this series, I discussed suggestions from experts on how to begin smart city initiatives. One of those experts, Dr. Boyd Cohen, created a model he calls the Smarter Cities Wheel. IBM has also developed a model that is reminiscent of Dr. Cohen's Wheel. The IBM model shows how it believes the three pillars of a city discussed above are interconnected.

Like most organizations involved in smart city initiatives, IBM believes that data collection and analysis is the undergirding that makes such initiatives useful. IBM's site states:

"As demands grow and budgets tighten, solutions also have to be smarter, and address the city as a whole. By collecting and analyzing the extensive data generated every second of every day, tools such as the IBM Intelligent Operations Center coordinate and share data in a single view creating the big picture for the decision makers and responders who support the smarter city."

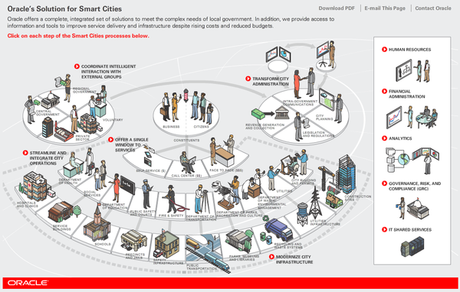

In Part 2 of this series, I noted that participants in a study published by the Institute for the Future expressed some concern that companies like IBM are trying to establish data monopolies that could be used to hold cities hostage in the decades ahead. IBM obviously sees itself as providing a much-needed service that cities can't provide for themselves. The company offers a nifty interactive Smarter Cities experience that can be explored at your leisure. Of course, IBM isn't the only global company that sees business opportunities in helping cities operate more efficiently. Oracle has its own interactive website that highlights its solutions for smart cities. The launch page for that interactive site also shows how Oracle sees connectivity within an urban setting (with business and citizens being the focal point).

Although the site explains that "Oracle offers a complete, integrated set of solutions to meet the complex needs of local government," some people, like Greg Lindsay, believe that companies like Oracle, IBM, and Cisco are "offering 'smart city in a box' solutions" that don't take into account the nuanced complexities that make each city unique. ["The Battle for Control of Smart Cities," Fast Company, 16 December 2012] See Part 2 of this series to learn more about Lindsay's concerns. Cisco's offering is called Smart+Connected Communities. Cisco's Shane Mitchell explains, that "the main barrier to adopting [smart city] solutions is the complexity of how cities are operated, financed, regulated, and planned." ["Smart City Frameworks: A Systematic Process for Enabling Smart+Connected Communities," Cisco Blog, 10 October 2012] Rather than offering a set of solutions, Cisco begins with "a 'Smart City Framework' designed to move the Smart City debate from merely an academic or esoteric discussion to a call for action." The framework is shown below.

Mitchell explains, "The Smart City Framework ... describes a potential process that will help key stakeholders and city/community participants 1) understand how cities operate, 2) define city objectives and stakeholder roles, and 3) understand the role of ICT within physical city assets." I agree with Mitchell that all stakeholders must be involved in smart city initiatives. As I wrote in Part 2 of this series, the only way to move forward is to embrace public/private partnerships that benefit both sectors." Terry Kirby agrees with that position. He writes, "When it comes to achieving the high-tech, sustainable, and smart cities of the future, there is one word that sums up the pathway to success: partnership." ["Getting smart cities connected," The Guardian, 2012] He continues:

"Imaginative and collaborative partnerships between local authorities, utilities, universities and the private sector – whether it is bus companies or software providers – are the defining characteristics of 'smart thinking', according to leading figures in cities around UK and Europe. All agree that so-called 'smartness' – which at its most basic level is about using new technology to improve lives – is necessary to adapt to the demands of urban growth. ... These kind of partnerships can range from multi-agency infrastructure ventures aimed at transforming the lives of millions, to simple projects improving digital access for everyday users of public services. They include new ways of using mobile phones and smartcards to pay for a wide range of goods and services, to schemes designed to recycle waste water for heating."

The editors at Scientific American conclude:

"The most hopeful impact of city life may be its effect on the mind. Humans are social animals; we draw stimulation from other minds close at hand. Plato and Socrates both lived in fifth-century b.c. Athens, a city-state. Galileo and Michelangelo lived in Renaissance Florence. Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak grew up in a western U.S. conurbation that includes Silicon Valley. The young, agile minds at work on the next Big Thing are probably tweeting—they live, as author William Gibson points out, ... in a kind of digital meta city. Chances are, they are living in a physical city, too. Technology is reshaping city life and making it more intellectually productive, but it will not soon replace the easy interchange of ideas that comes from casual proximity, the cornerstone of city life."

While some pundits believe that smart city initiatives may drain city centers of their vitality, I agree with the editors at Scientific American that making cities more livable will actually increase the vitality of cities and make urbanization a boon rather than a bane to mankind. Gerd Leonhard, chief executive of the business thinktank The Futures Agency, agrees. He told Jemima Kiss, that "the more digitised our lives become, the more we will value real experiences. 'The landscape of the cities of the future will be a huge place to do the things that don't work in digital form – food, culture, contemplation. Digital tools drive us to want to have the actual experience much more than before.'" ["City design: A digital revolution," The Guardian, 2012] The thing I appreciate most about the smart cities movement is its optimism. There are enough Cassandras in the world warning us of impending doom. Optimists bring about progress and, as the IBM website states, progress is the watchword.