I spent most of my childhood and youth in Genoa, the capital of Liguria.

Unlike other Latin American immigrants of European descent, my parents settled on the Ligurian coast and stayed there for more than two decades.

That is why this land of historic sailors, of unparalleled natural beauty, has remained so imprinted in my memory.

Said the great author Alexandre Dumas:

‘Lying at the bottom of its gulf with the careless majesty of a queen ... Genoa comes, as it were, to meet the traveller’ (A. Dumas, 1841).

It is a pity that travellers pass through it most of the time in haste, preferring other places in Liguria, such as Cinque Terre or Portofino, thus missing the opportunity to discover a city rich in history, hidden treasures and suggestive corners.

The history of Genoa is told above all along Via Garibaldi ei Rolli, home to marvelous residences little known to Italians but rich in extraordinary works of art.

The charm of this city wedged between the mountains and the sea, fragmented between past and present, crossroads of different peoples and cultures (it is not by chance that the medieval name of Genoa is Janua, or ‘gate’ in Latin), has attracted the attention of writers, poets and songwriters, who in their verses have spoken of its beauty, its contrasts, its hidden soul.

First of all Fabrizio de André, who is celebrated today with a small but wonderful museum in Via del Campo 29. Although Genoa is known above all for its Aquarium, the ancient maritime republic encloses within its walls wonderful testimonies of its glorious past, but also bold and modern works that have made it a sort of capital of modern Italian architecture.

Strolling through the city, you can admire noble palaces and ancient churches, lose yourself in the labyrinth of characteristic alleys (carroggi) in which the old city center is organised, visit interesting museums, let yourself be surprised by the symbols of the city, the new Genoa, which looks to the future but is a magnificent guardian of an ever-present past.

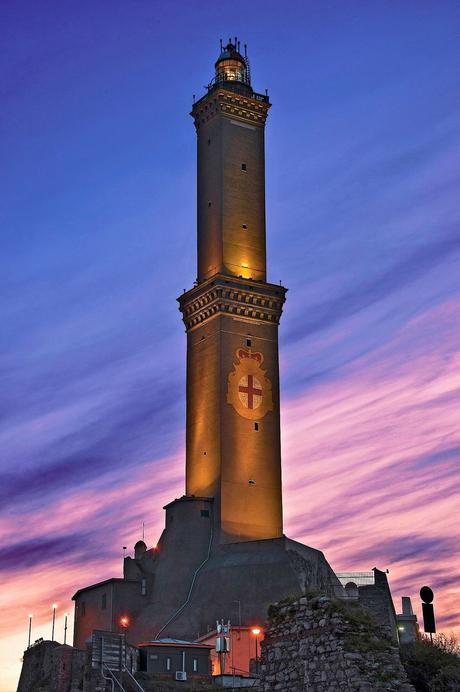

We begin this virtual tour by the symbol of Genoa, La Lanterna (the lighthouse), emblem of a city that developed on the basis of its port (and still continues to do so today, adding to the cargo port a tourist port where cruise ships from all over the world arrive, right in the center of the city).

The Lighthouse of Genoa.

Proof of the maritime vocation of this city is its lighthouse, commonly called ‘the Lantern’, which has always been the symbol of Genoa. Standing 77 metres high, the historic tower rises on the remains of a 40-metre hill, making it approximately 177 metres above sea level.

Created to signal ships entering the port but also to control their movement within the port, the tower was built in the 14th century on the site of a lighthouse that had existed since 1128 and operated with a wood-burning system (bonfires).

In 1326 the first olive oil lantern was installed and in 1340 the municipal coat of arms was painted on the lower part of the tower.

Its current appearance is the result of the reconstruction carried out in the 16th century and despite the interventions following the events of the war and the lightning strikes, the lantern appears as it did then: a tower with two slender superimposed volumes with a gallery at the top of each of them (you can reach the first terrace), an interior staircase with 172 steps, a lantern inside which the lighting elements are located.

Attached to the tower is the Lantern Museum, a multimedia museum dedicated to the city and the provincial territory, which can be reached by an 800-metre walk from the Ferry Terminal along the old city walls to the lighthouse.

The Lanterna is located at the eastern end of the district of Sampierdarena, on an isolated rock that is today entirely inserted in the port context, the extreme tip of what was once the promontory of San Benigno that divided the ancient municipality of Sampierdarena from that of Genoa.

The site where it was built was called a promontory because, before the hand of man redesigned the contours of the Genoese bay, it was surrounded on three sides by the sea. To the west, the hill bordered the ancient port of Genoa, what is now the old harbor. Over time the hill took the name Capo di Faro or San Benigno, after the name of the convent of the same name that stood on it. Today, in fact, the hill no longer exists, having been razed in the second half of the 1920s to create new spaces for the town, the port itself and its production facilities, and the only thing that remains is precisely the small rocky branch from where the lighthouse stands.

At the same time, between 1920 and 1930, work was carried out to enlarge the port of Genoa, with the creation of the new Sampierdarena quays, obtained by means of a major filling in of the sea. After the operation, the Lanterna rock no longer lies directly on the sea, but a short distance from it, near the quay of Ponte San Giorgio.

The Lantern Gate

Since the Lanterna stood on the main communication route between Genoa and the west, until the San Benigno hill was excavated in the early 20th century, when the so-called seventeenth-century Mura Nuove (New Walls) were built, a gate was built inside them exactly at the foot of the Lanterna.

Thus, as historian Federico Donaver recalls, the old gate, kept in place until its demolition in 1877, was flanked by a new one built between 1828 and 1831, called Porta Nuova, Porta della Lanterna or Porta del Chiodo after its designer, General Agostino Chiodo. In fact, as Donaver himself wrote, the same gate and the adjacent streets took ‘the name of the Lanterna or Lighthouse for sailors that rises 127 m above sea level, whose construction dates back to 1549’. The double-arched gate was carved into the rock face and originally had two drawbridges supported by chains running on bronze wheels, soon replaced, due to changing practical needs, by a fixed gangway. The neoclassical façade is built of promontory stone (taken from the same hill behind the Lanterna) and white Carrara marble, a combination that counts illustrious precedents in the city's architecture. Remarkable is the sculptural detailing, consisting of metopes, jellyfish heads placed in the keystone and the coat of arms group.

The gate building was demolished in 1935. As a result of controversy, in order to preserve the memory of the gate, the façade alone was dismantled and rebuilt in its current position, leaning against the Lanterna wall, about fifty metres to the south and rotated 90° from its original position, losing its original function as a gate.