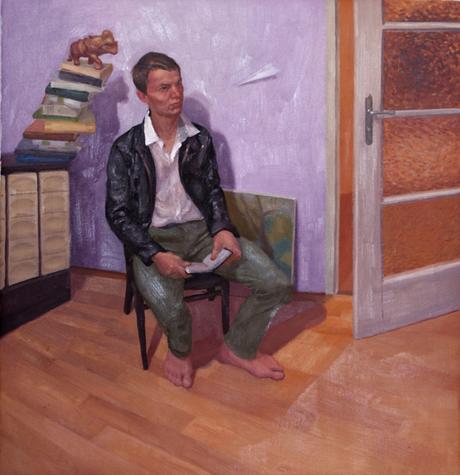

The enabler (Dr Jacques Pienaar) © Samantha Groenestyn (oil on linen)

It is, of course, extremely unpopular to paint the way that I do—representational pictures, ‘stuff that looks like stuff,’ images thoroughly stripped of their purpose by the speed and apparent accuracy of photography. Though I’m finding pockets of representational painters around the world, we are undeniably on the periphery, and perhaps rightfully so. Different demands are made of art now, and art must adapt accordingly. I cling to what I do because it is the most satisfying thing I know to do, and because the roots of it run deep and strong all the way back through our Greek heritage, a heritage of which I’m proud and a willing inheritor. I see this akin to a respect for our philosophical tradition and its Platonic genesis. This is where we have come from; this Greek impulse is part of our cultural and intellectual makeup.

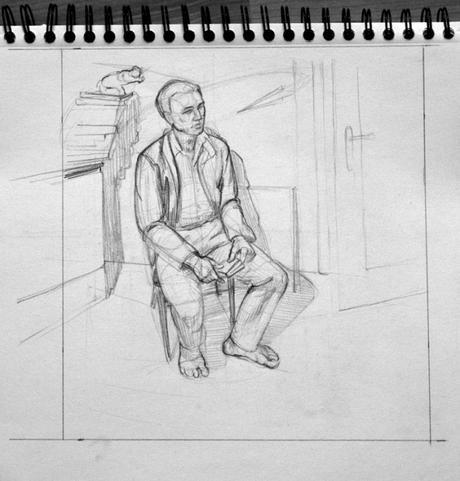

Enabler (composition study)

And the Greeks, as Gombrich points out in a chapter on ‘Reflections on the Greek revolution,’ may be credited with a truly remarkable deviation. ‘There are few more exciting spectacles in the whole history of art than the great awakening of Greek sculpture and painting between the sixth century and the time of Plato’s youth toward the end of the fifth century B.C,’ he (1959: 99) writes with palpable enthusiasm. It is no coincidence that at the very time Plato was penning his timeless philosophical observations, Greek artists were asking new questions of the physical world and expressing wholly new observations of it in their work. Plato himself challenged this frighteningly unbridled power art was summoning, famously equating illusion with delusion, for this revolution unfolded during his own lifetime.

For until the Greeks invented mimesis—the attempt to ‘match’ the visible world, which Gombrich (1959: 99) contrasts with the more widespread and primitive impulse simply to ‘make’—equally impressive civilisations were demanding something wholly different from art. The Egyptians, the Mesopotamians and the Minoans were concerned with a fixed, eternal art. Uninterested in particulars, their art rather ‘held out a promise that its power to arrest and to preserve in lucid images might be used to conquer’ the ‘irretrievable evanescence of human life’ (Gombrich 1959: 107-8). Keats expresses the deliciousness of such a timeless power in his ‘Ode on a Grecian urn’:

‘Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave

Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare;

Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though winning near the goal—yet, do not grieve;

She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss,

For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair!Ah, happy, happy boughs! That cannot shed

Your leaves, nor ever bid the Spring adieu.’

And, indeed, such ritualistic art never lost its attraction. ‘In the time of Augustus,’ Gombrich (1959: 124) notes, ‘there are already signs of a reversal of taste toward earlier modes of art and an admiration of the mysterious shapes of the Egyptian tradition.’ The middle ages, rather than a period of decadence and darkness, might be seen as a time of reaffirmation of this powerful mode of art. Clear, schematised, generalised, symbolic motifs executed with primitive clarity work a sort of magic that is difficult to resist. Gombrich (1959: 124) argues that it is misleading to describe art’s history in terms of progress or decline, and considers the Greek ‘revolution’ a true innovation, a notable break in the story, but he argues that the reclamation of schematic art ought not ‘be interpreted as a fresh revolution in favour of new ideals. What happened here looks much more like another process of natural selection, not a directed effort by a band of pioneers, but the survival of the fittest; in other words, the adaptation of the formulas to the new demands of imperial ceremony and divine revelation. In the course of this adaptation, the achievements of Greek illusionism were gradually discarded.’ Artists overwhelmingly produced what they were required to.

The appeal of such ‘conceptual art,’ as Gombrich classifies it—and this arguably applies equally to the reductive abstract art of our own time and more recent history—is not difficult to account for. ‘What is normal to man and child all over the globe is the reliance on schemata, on what is called ‘conceptual art’ (1959: 101). The art which today holds sway appeals to universals, to the general, to broad human experiences in an amusingly primitive way. ‘With the beholder’s questioning of the image, the artist’s questioning of nature stopped’ (1959: 124). It is the Greeks alone who have demanded something altogether different of the image: ‘[Egyptologist Heinrich] Schäfer stressed that the ‘corrections’ introduced by the Greek artist in order to ‘match’ appearances are quite unique in the history of art. Far from being a natural procedure, they are the great exception’ (Gombrich 1959: 101).

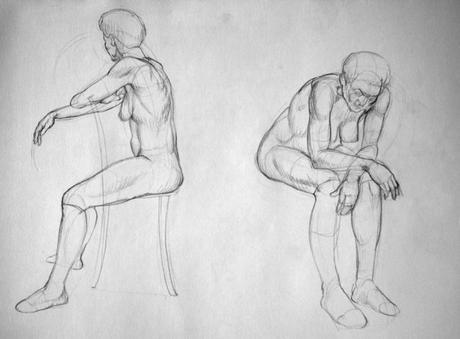

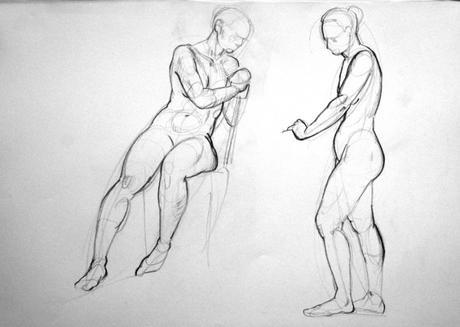

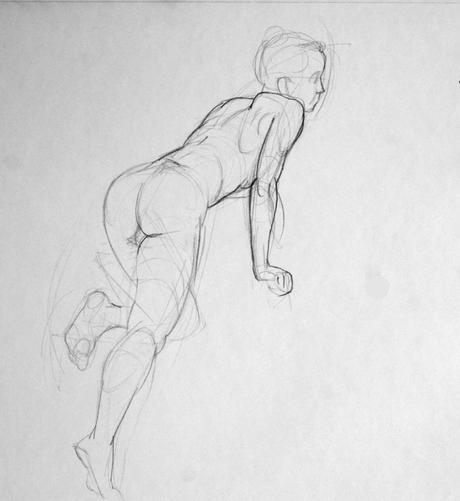

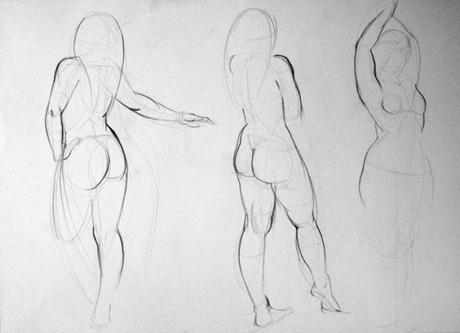

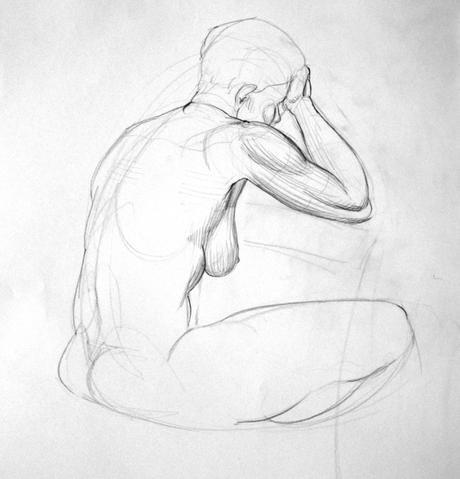

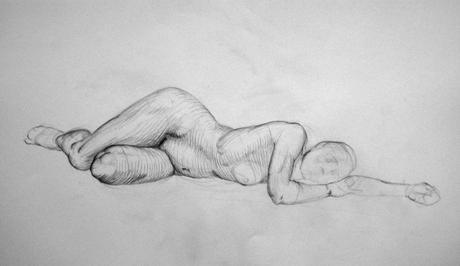

The nude is central to the Greek tradition, and has survived in western art even until our own time. Yet I am not clear on what its role should now be, stripped of its Greek philosophies of embodied ideas, of godlike perfection in supple human form. The role of the nude has changed dramatically since its invention by the Greeks. As Clark (1985: 337) writes, the workshops of the middle ages which trained artisans—manual workers—gradually gave way to academies which urged more intellectual pursuits. ‘When this old discipline of grinding colours, sizing panels and copying approved models was removed … what new discipline took its place? Drawing from the nude, drawing from the Antique and perspective.’ The nude became inextricably linked with cleverness in art, with intellectual abstractions (Clark 1985: 337-8):

‘Instead of the late Gothic naturalism based on experience, [drawing from the nude] offers ideal form and ideal space, two intellectual abstractions. Art is justified, as man is justified, by the faculty of forming ideas; and the nude makes its first appearance in art theory at the very moment when painters begin to claim that their art is an intellectual, not a mechanical activity.’

The Greeks made an unprecedented leap in grasping after mimesis, in matching their observations. But as Gombrich (1959: 121) argues, ‘we mistake the character of this skill if we speak of the imitation of nature. Nature cannot be imitated or ‘transcribed’ without first being taken apart and put together again. This is not the work of observation alone but rather of ceaseless experimentation.’ Here the Italians emerge, smug in their mastery over nature, with their newly intellectualised painting, built around the worship of the nude: ‘there is no doubt that the Florentines valued a demonstration of anatomical knowledge simply because it was knowledge and as such of a higher order than ordinary perception’ (Clark 1985: 340).

The nude persisted throughout the twentieth century, but she was shamefully ravaged. The fact that the nude became almost exclusively female is significant, and Clark (1985: 343) links this change to the Florentine pride in knowledge. ‘No doubt this is connected with a declining interest in anatomy (for the écorché figure is always male) and so is part of that prolonged episode in the history of art in which the intellectual analysis of parts dissolves before a sensuous perception of totalities.’ Art, of course, grew in its intellectual aspirations, forced its way (perhaps unjustifiably) into the universities, and discarded anything tainted by technique, scrambling instead after a pitiable faux-philosophy, loosely held together by sensual feminine curves.

What are we to make of the nude and of mimesis in our own time? Can we turn back to our cultural origins and embrace the Greek intent? This feels false in the wake of Christianity and its accompanying shame for our bodies, our gothic repulsion to the human form, our appetite for punishment and decay. And there is something surprisingly appealing in the ruthlessly grotesque German representations that Greek perfection never touches. The Judeo-Christian tradition is equally a part of our cultural fabric and our western attitudes. Perhaps, then, the nude is a private and academic exercise, and once mastered it serves only as a support to our other representational endeavours. Perhaps the interest in the nude that has resurfaced in the modern ateliers is a propitious start, but is not justified in being considered art. Ryan has spoken warily of the present-day ‘cult of the student:’ the misdirected celebration of studio nudes as ends in themselves. I’m inclined to agree.

Certainly, the Greeks began something wholly European, a complete anomaly in the story of art. Our thoughts, our perception are unavoidably influenced by their invention. I will be so bold as to say there is something worthwhile in this, something worth preserving and carrying forward. Something beyond the schematic, conceptual art that even children are capable of, that every other culture has independently produced. ‘What most of us lack in order to be artists,’ argues Dewey (1934: 75), ‘is not the inceptive emotion, nor yet merely technical skill in execution. It is capacity to work a vague idea and emotion over into terms of some definite medium.’ Far from teaching us how to be human cameras, the Greeks taught us how to override the schematisation and simplification our brains naturally strive for and gave us an intelligent way to think with our hands. And I have no desire to abandon such a rich inheritance.

Clark, Kenneth. 1985 [1956]. The nude: A study of ideal art. Penguin: London.

Dewey, John. 1934. Art as experience. Minton, Malch & Company: New York.

Gombrich, E. H. 1959. Art and Illusion: A study in the psychology of pictorial representation. Phaidon: London.

Keats, John. 2006. Selected poems. Ed. Deborah West. Oxford University: Oxford.