Irecently looked up the final of the Barcelona Open, and I loved it considerably more than the previous match between Nadal and Djokovic in Montecarlo, which seemed a bitter blast through the cheeks, a fictitious way of kissing Au revoir à Paris on a cupid’s buttocks, having established that the big Serbian would not be loosing control of his mental edge so quickly there. (I am not overfond of this sort of sport romances—but let me continue sweetly.) Even though I did not foresee this work of inquiry and comment, I found myself in a flora of metaphors; I felt the urge to talk on the subject and unburden my thoughts to my readers. True, in this tennis match Rafael Nadal has unburdened himself pretty thoroughly, and the picture of his renewed health on clay is quite clear and complete—maybe a little too complete, architectonically, since the spectator cannot help feeling that is has expanded and elaborated to the detriment of certain other ghosts and darker psychological pages ousted by it. But a commentator’s obligations cannot be avoided, however dull the information he must collect and convey. Hence this sketch.

It appears that since the early beginnings in the 1920s, long before the dominance of Guillermo Vilas [1], clay-court tennis was involved in some appalling psychokinetic manifestations that lasted for nearly a century. Initially, one gathers, the poltergeist meant to impregnate the disturbance with the identity of heroic players, past and present, who had either retired or failed to qualify; the first task to perform for Nadal here was to spin his way out of the present trouble and beyond the familiar ghost of Djokovic that had kept his inside-out forehead half-paralyzed (it took him all the first set to turn those burn-out scars and move into the tie-break). Rafa had the fetish destroyed soon after he rectified the aim of his shots of a few inches inside the court, traveling along the corridor past the open door of his intact “inner” sanctuary and incurring the wrath of David Ferrer who was besides himself with fear and distress (he utterly sank into dark, disturbing thoughts at the crumbling edge of each set, after an organic performance of amazing confidence and variety).

Next, the scene of action switched to the left side, where Ferrer was found scoring point after point on every short rebound of his rival, anticipating with quick footwork the point of impact and trying to take advantage of all the richer and rarer matters of Nadal’s touch, the way a snowball prematurely rolls in the icebox; and all the knockings, of course, especially when compared to Rafa’s quixotic ans powerful twisting, landed flatly and safely, with the radiant clarity that shines through a raspberry-colored silk shade.

Other incidents followed, such as short engagements of serve-and-volley, Ferrer finding a few exquisite drop-shots by tapping the ball when it was still ascending, or Nadal pushing the ambitions of his geometry flung wide as if by the blast of an explosion (two beautiful variants of this branched off when the initial score was locked at 2-2). But soon the poltergeist ran out of ideas in connection with Djokovic and became, as it were, more eclectic. All the banal motions of objects such as saucepans crashing in the kitchen or chairs waddled away to reassemble the pantry slowly settled into a muted echo-chamber. Tennis hieroglyphic gradually formed into the imposing if still vague contours of a mighty plan; subliminally—an unconscious realization bathed in the mild moonlight of respect and friendship—the work of these two clay-masters became forcibly subdued and almost suppressed by the calm presence of the greatest surface specialist.

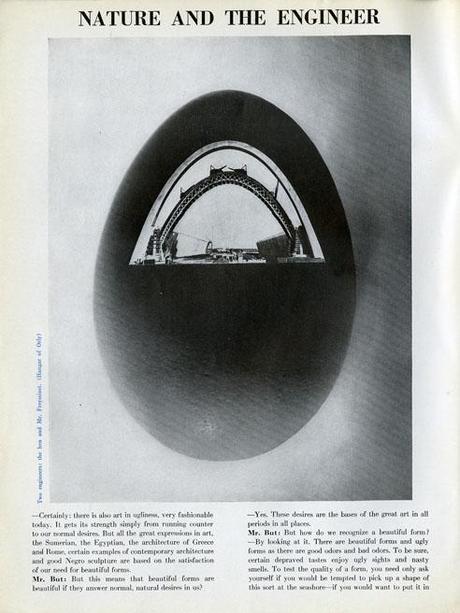

This is, perhaps, what I most like about Rafa Nadal—and I proceed to say, this mature Nadal. The heavy, ponderous sounds of his shots still hit us like strained nerves, but in the serious tenacity of the young man we feel a first silent intimacy with redoubled force. The movements of his serving technique are still a framework of calculations, spreading out like mechanical diggers put to work; yet the cranes circling in the air began to slumber a bit, as if by intoxication of sea air. The fantastic sum of figures stacked up into each ball [2] are no longer the fruit of heated frenzy, with occasional flashes of disgust, but the capable scaffold of a small, upholstered study. Hearing the remoteness of this learned bird (which, by a single stroke of fancy, I might identify as a waxwing), Ferrer might have thought a feeble steering of a musical theme, a new genetic variant of the same clay-tune, preserved in Catalunya and Majorca through political pollination. And how curious it is that we do not perceive a mysterious sign of equation between the Spanish Hercules springing forth from a neurotic child and the boisterous ghost of Vilas, his martial curls bristling with obsolete passion.

This, I understand, is also the semitransparent envelope left on a tree trunk by an adult cicada that has crawled up dark times to emerge. Nadal moves with majestic generosity, an elegant shyness and a rather coquettish way of nibbling the tip of his trophies. Unlike some of his fellow celebrities (let me speak with a rude tongue), in him one finds no Dostoevskian rows, and no Tolstoian nuances of snobbishness expanded to an insufferable length. In his emerald empty case he left behind by now, Nadal would be roughly comfortable in the green grass of England—that royal game of British poets—as well in a ghoulish French dance, and even in the springtime of gray-blue Copenhagen. Maybe there is something rather eighteenth-century in him, or even a seventeenth-century mirage. But I must go now. I think my telephone is ringing.

So much for Rafa Nadal’s last triumphant song. ♦

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Notes.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Guillermo Vilas is a left-handed baseliner, born in the seaside resort of Mar del Plata in Argentina, whose best year was 1977 and whose records on clay have either been beaten or matched recently by Rafael Nadal.

[2] I illustrate my point with a plate taken from Plus 1, a 1938 architectural magazine designed by Herbert Matter.