So Monica was like, “What are you doing here, Chandler?” and Chandler was like, “Uhh nothing” and then Monica was like, “Why are you here with Phoebe?” and Chandler was like, “I don’t know,” and Monica was like, “Whatever!”

Quotative “be like” probably gets on your nerves. Unfortunately for you, it spread like wildfire in the latter half of the 20th century and today is used by native and non-native speakers alike as often as they use traditional say-type quotatives. What is its structure, when did it arise, and why did it spread so quickly? This post offers a possible explanation, based on evidence dragged up from the depths of the Google Books Corpus. To appreciate that evidence, however, we need to start with some discussion of this quotative’s formal properties.

1

One interesting property of quotative “be like” is its ambiguous semantics. In some contexts, it is a stative predicate that denotes internal speech, i.e., thoughts reflexive of an attitude. In other contexts, it is an eventive predicate denoting an actual speech act. Sometimes, the denotation is ambiguous, as in (1):

(1) Monica was like, “Oh my God!”

. . . Did Monica literally say “Oh my God!” or did she just think or feel it?

Another interesting property of quotative “be like” is that it disallows indirect speech.

(2a) Monica was like, “I should go to the mall.”

(2b) *Monica was like that she should go to the mall.

(2c) *Monica was like she should go to the mall

Quotative say of course allows indirect speech:

(3a) Monica said, “I should go to the mall.”

(3b) Monica said that she should go to the mall.

(3c) Monica said she should go to the mall.

Haddican et al. (2012) recognize that quotative “be like” is immune to indirect speech due to its mimetic implicature. (2b) cannot be allowed because quotative “be like” always means something more along these lines:

(4) Monica was like: QUOTE

Given the implied mimesis of this construction, it makes no sense, as in (2b) and (2c), to add an overt complementizer and to change person/tense to produce an indirect, third person report. This property is shared by all uses of quotative “be like,” whether in their stative or eventive readings.

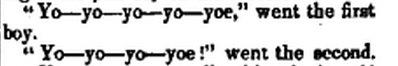

But there’s more to it than a mimetic implicature. Schourup (1982) points out that quotative “go” also shares this mimetic property (although he does not frame it as such). As expected of a quotative with a mimetic implicature, quotative “go” likewise does not allow an indirect speech interpretation via addition of an overt complementizer and shifts in person/tense:

(5a) Monica goes, “I should go to the mall.”

(5b) *Monica goes that she should go to the mall.

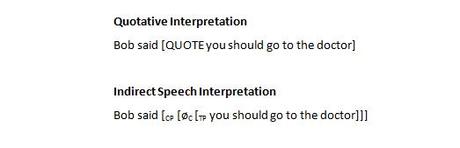

Why should these innovative quotatives be so immune to indirect speech and so committed to direct quote marking? Schourup suggests that quotative “go” (and, by extension, quotative “be like”) arose precisely to meet English’s need for a mimetic, unambiguous direct quotation marker. Prior to the occurrence of these new quotatives, English lacked such a marker. Consider (6a) and (6b) below:

(6a) When I talked to him yesterday, Chandler said that you should go to the doctor.

(6b) When I talked to him yesterday, Chandler said you should go to the doctor.

There is no ambiguity in (6a). The speaker of this utterance clearly intends to convey to his interlocutor that Chandler said the interlocutor should go to the doctor. (6b), however, introduces ambiguity. The utterance in (6b) can be interpreted in two ways: a) Chandler said the speaker of the utterance (i.e., I) should go to the doctor; b) Chandler said the speaker’s interlocutor (i.e., you) should go to the doctor. With orthographic conventions, of course, this ambiguity disappears:

(6c) When I talked to him yesterday, Chandler said, “You should go to the doctor.” (So I went.)

However, unlike other languages, spoken English has no “quoting” conventions—it has no direct quote markers for unmarked speech. It is unclear if (6b) is a true quotative or merely an indirect report on speech with a null complementizer.

We can imagine speakers needing to clarify this ambiguity:

JOEY: When I talked to him yesterday, Chandler said you should go to the doctor.

ROSS: Wait, he said I should go or you should go?

This ambiguity arises with say-type verbs whenever the complementizer that is omitted. It is traditionally understood that English differentiates between direct quotatives and indirectly reported speech via shifts in person and/or tense. However, the overt complemetizer is really the central feature of this differentiation. Without an overt complementizer, it is never entirely clear if the embedded clause is a direct quote or an indirect report of speech. Here’s another example:

(7) JOEY: Chandler said I will be responsible for the cat’s funeral.

Without the aid of quote marks, we cannot know whether Chandler or Joey is responsible for the cat’s funeral, even though the embedded clause contains a shift in both person and tense. Of course, if Joey wants to convey that Joey himself will be responsible for the cat’s funeral, he can simply add the overt complementizer: “Chandler said that I will be responsible . . .” However, if Joey wants to convey that Chandler has decided to be responsible, Joey has no way to convey it unambiguously with say-type verbs. He must resort to an indirect speech construction with an overt complementizer. Alternatively, he can resort to non-structural signals: a short pause, a change in intonation, or a mimicry of Chandler’s voice. Or he must abandon say-type constructions altogether and convey his meaning some other way.

Quotative “go” and quotative “be like” solve this ambiguity. These innovative quotatives always signal that the following clause is mimetic, a direct quote of speech or thought. Many languages—Russian, Japanese, Georgian, Ancient Greek, to name just a few— have overt markers to ensure that interior clauses are understood as being directly quoted material, whether or not those quoted clauses contain grammatical shifts (though of course they often do). The quotatives “go” and “be like” serve this same purpose. They are structural, unambiguous markers for direct speech, which is why one cannot use them for indirect speech, and which is also why they have spread so widely and quickly: they have met a real need in the language.

Quotative “go,” however, is attested long before quotative “be like.” The Oxford English Dictionary puts the earliest usage in the early 19th century, initially as a way to mime sounds people made, then later as a way to report on actual speech. Here’s an example from Dickens’ Pickwick Papers:

So, although I have said that both quotative “be like” and quotative “go” met a need in English for an unambiguous direct quotation marker, it was “go” that in fact met the need first, by at least a century. This historical fact leads me to suspect that quotative “be like” met a slightly different need: while quotative “go” became a direct quotation marker for speech acts, quotative “be like” became a direct quotation marker for thoughts. As Haddican et al. rightly note, an innovative feature of these quotatives is that they allow direct quotes to be descriptors of states. In other words, the directly marked quotes of “go” denote external speech; the directly marked quotes of “be like” primarily denote internal speech, i.e., thoughts or attitudes. I believe this hypothesis is supported by the earliest uses of quotative “be like,” to which we now turn:

2

Today, young native and non-native speakers of English frequently use “like” as a versatile discourse marker or interjection in addition to its use as a quotative (D’Arcy 2005). D’Arcy provides two extreme examples of discourse marker “like.” Both are taken from a large corpus of spoken English:

(8) I love Carrie. LIKE, Carrie’s LIKE a little LIKE out-of-it but LIKE she’s the funniest, LIKE she’s a space-cadet. Anyways, so she’s LIKE taking shots, she’s LIKE talking away to me, and she’s LIKE, “What’s wrong with you?”

(9) Well you just cut out LIKE a girl figure and a boy figure and then you’d cut out LIKE a dress or a skirt or a coat, and LIKE you’d color it.

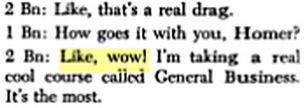

This usage does not become noticeable in available corpora until the 1980s, so nearly all papers that I have read assume that discourse marker “like” and qutoative “be like” arose more or less in tandem during the 1970s, becoming common by the 1980s. However, using the Google Books Corpus, I was able to find an early use of “like” that presages quotative “be like.” This early use also seems to set the stage for the versatile discursive uses of “like” seen in (8) and (9). This early use is the expression, “like wow.” It seems to have arisen during the 1950s (though perhaps earlier) in the early rock n’roll scenes in the Southern United States. Here are some examples.

The first is from 1957: a line from a rock n roll song by Tommy Sands:

(10) When you walk down the street, my heart skips a beat—man, like wow!

The second is from a 1960 issue of Business Education World:

(11) Like, wow! I’m taking a real cool course called general business. It’s the most.

The third is from a novel called The Fugitive Pigeon, published in 1965:

(12) But all of a sudden you’re like wow, you know what I mean?

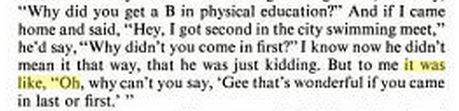

And by 1971, we have a full example of quotative “be like,”— note that this early occurrence uses an expletive as the subject:

(13) But to me it was like, “Oh, why can’t you say, ‘Gee that’s wonderful . . .’”

These early uses of “like wow” in (10) and (11) denote a stative feeling or attitude rather than any kind of eventive speech act. This is especially clear in (11), where the expression is a direct response to a question about how the speaker is feeling. The quotative in (13) likewise seems to be a stative predicate rather than an eventive one. In fact, in nearly all of the earliest 1uses of quotative “be like”—from the 1970s and early 1980s, as reported in the Google Books Corpus—the intention is to denote a feeling or attitude, not a direct quote of a speech act. Such eventive predications don’t become common until the 1990s and 2000s.

“Like wow,” then, arose in 1950s slang as a stative description. However, the sentence in (14) below suggests that wow was not interpreted as a structurally independent interjection but as an adjective. This is from a 1960 edition of Road and Track magazine:

(14) Man, that crate would look like wow with a Merc grille.

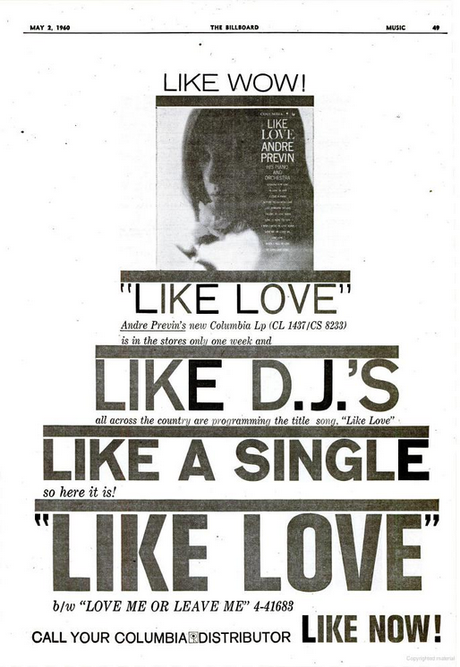

It is possible that like is an adverb here, but in my estimation it is most likely still a garden variety manner preposition that has innovatively selected for a bare adjective. Typically, like as a preposition only selects NPs as its complement. However, with the advent of “like wow,” it loosened its selection requirements and began to select for adjectives as well. And not just adjectives. The bottom line in this advertisement from Billboard magazine in May 1960 demonstrates that it also began to select for adverbs:

Apparently, in the 1950s and early 1960s, like became a popular and versatile manner preposition. Once like loosened its requirements to select AP complements, it’s easy to see how it could start selecting quotes, thus becoming a new direct quote marker (like narrative “go”); and given the stative denotation of the original phrase “like wow,” it’s also easy to see why stative to be would become the verbal element in this quotative rather than a lexical verb like act or go. Indeed, it appears that the first uses of quotative “be like” were entirely restricted to the phrase “like wow,” ensuring that subsequent uses would likewise have stative readings. (The ad above also shows how easy it would be for like to become an all-around discourse marker once it began to select for a wider range of phrases.)

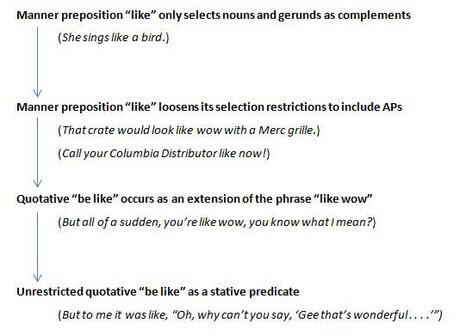

So, based on the timeline of evidence in the corpus, I posit the following evolution:

The emergence of quotative “like”

I follow Haddican et al. in assuming that like in quotative “be like” is still a manner preposition. However, while they assume the preposition did not undergo any change, I argue that like became more versatile in its selection restrictions. This versatility allowed it first to select APs, then to select quotes. Initially, this quotative construction was just an extension of the phrase “like wow,” but it soon began to select any quoted material. And from the beginning, this quotative possessed two features: a) it had an obvious mimetic implicature, ensuring that it would be a direct quote marker, similar to narrative “go”; and b) it had a stative denotation, due to the stative dentation of the original phrase “like wow,” ensuring that the directly marked quotes were reflective of internal speech, i.e., thoughts or attitudes.

A corpus analysis by Buchstaller (2001) has shown that, even today, quotative “go” is much more likely than quotative “be like” to frame “real, occurring speech” (pp. 10); in other words, “be like” continues to be used more often as a stative rather than eventive predicate. As I mentioned earlier, Haddican et al. are correct that one innovative aspect of quotative “be like” is that quotes are now able to be descriptors of states; however, I believe they overstate the eventive vs. stative ambiguity that arises in these quotatives. Most of the time, in real contexts, they are as unambiguously stative as they are unambiguously mimetic of the state. Haddican et al. themselves note that even these eventive readings are open to clarification. Asking whether or not someone “literally” said something sounds much odder following a say-type quotative than a “be like” quotative with a putatively eventive reading.

3

Nevertheless, as I showed at the very beginning of this post, there are instances where quotative “be like” seems to denote an eventive speech act. Linguistically, this is odder than it sounds at first. A single verbal construction—like quotative “be like”—should not have a stative and eventive reading. This ambiguity can only happen for two reasons: either there is some special semantic function at work in this construction, or there are in fact two separate quotative constructions, each with its own syntactic structures.

It is tempting to see a correlation between this ambiguity and the putative ambiguity between stative be and eventive be, also known as the be of activity. Consider the following sentences:

(15) Joey was silly.

(16) Rachel asked Joey to be silly.

Both forms of be select an adjective; however, (16), unlike (15), can be taken to mean that Joey performed some silly action. In other words, the small clause in (16) seems to be an eventive predication, not a stative one. It has been argued (Parsons 1990) that this eventive be is not the usual copular form but a completely different verb that means something like “to act”—in other words, English to be is actually a homophonous pair of verbs, similar to auxiliary have and possessive have. Perhaps this lexical ambiguity in be is related to the eventive vs. stative ambiguity in quotative “be like.” The stative reading arises when stative be is involved; the eventive reading arises when the eventive, lexical be is involved.

Haddican et al. argue against this line of thought. Diachronically, we know that quotative “be like” has arisen rapidly in many varieties of English, and that in all of these varieties, the semantics are ambiguous. But if there are in fact two be verbs that underwent this quotative innovation, then we would need to posit two unrelated channels of change: one in which like+QUOTE became a possible complement of stative be and one in which like+QUOTE became a possible complement of eventive be.

This is actually a problematic claim, given that, presumably, stative and eventive be have different structures. The former undergoes its typical V to T movement in English; the latter, given its eventive semantics, would be expected to remain in the VP like any other lexical verb. These underlying structures would demand that we devise different processes by which qutoative “be like” arose. However, given the rapidity with which it did in fact arise, it is more probable that it arose via a single process—and the inevitable conclusion is that there is a single, stative verb to be that underwent the process. This conclusion is also verified by the auxiliary-like behavior of be in quotatives involving adverbs and questions:

(17) Ross was totally like, “I don’t care!”

(18) Was Ross like, “I don’t care”?

Although the ambiguous stative vs. eventive reading still occurs here, (17) exhibits raising above AdvP, and (18) exhibits subject-aux inversion. In other words, be in these quotatives behaves like an ordinary copular auxiliary, not a lexical verb. We therefore should not posit a separate, eventive be verb. We need another way to explain the semantic ambiguity of these quotatives.

Haddican et al. explain this ambiguity with Davidsonian semantics. Briefly stated, they argue that there is a single stative be verb—both in these qutoative constructions and in English more generally. However, be has a semantic LOCALE function that, in certain contexts, can localize the state in a short-term event, and this localization of an event can force an agentive role onto the subject, even when an adjective has been selected by be. So, in a sentence such as (19), be will have a denotation as in (20):

(19) Joey is being silly.

(20) [[be]] = λSλeλx. ∃s ϵS [e = LOCALE(s) & ARGUMENT(x,e)]

(20) takes a property of state S and localizes it into an event (a moment in which Joey was silly); in the right context, it is not a great leap to coerce this experiencer event into an agentive one. The application of these semantics to “(be) like” quotatives is straightforward:

In the state reading, be like is simply a stage level use of the copula, localised to the event in which the subject of be exhibited the relevant behavior. The eventive reading arises when the event mapped to is an agentive one, where the most plausible event of an agent behaving in a quotative manner is the relevant speech act. (Haddical et al. 2012 pp. 85)

In short, the ambiguity between stative and eventive “be like” arises from a semantic property that forces certain “states of being” to be processed as localized events whereby the experiencer of the event takes on an agentive role. In certain quotative contexts, the embedded quote is processed as an event, and the subject is understood as having caused that event, i.e, as actually saying something rather than just experiencing an attitude.

I agree that it would be better not to posit two homophonous verbs (stative be vs. be of activity) to account for the ambiguous stative vs. eventive denotations of quotative “be like.” Doing so requires two separate analyses and two separate channels of diffusion, which seems unlikely given the rapidity with which this quotative did in fact spread across many varieties of English. However, Haddican et. al’s application of Davidsonian semantics to explain the ambiguous readings runs into a problem in sentences like (21) below, as well as in the earlier example in (13):

(21) It was like, “Oh Mom, Can I film a movie in the house, it won’t be any problem at all.”

This is clearly an eventive predication of quotative “be like.” But instead of an agentive subject we have expletive it. Recall that Haddican et. al’s analysis relies on the notion that stative be has a LOCALE function that locates the state into a temporary moment or event. This localization can coerce an experiencer subject into the role of an agentive subject when the most likely reading (as above) suggests that the temporary event was an actual speech act. As Haddican et al. say themselves, “this event assigns an agentive role to the subject” (pp. 85). However, by definition, the expletive in (21) receives no theta role and can therefore be neither the experiencer of a state nor the agent of an event. And yet (21) clearly denotes an eventive reading: the speaker actually spoke the words, or something like them.

The fact that “be like” quotatives can take an eventive (or even a stative) reading when an expletive surfaces in spec-TP suggests that Davidsonian semantics do not explain the ambiguous eventive vs. stative readings associated with these quotatives. (The fact that “be like” quotatives exhibit both experiencer subjects and expletive subjects also suggests that the quote CP is the only obligatory argument assigned by “be like.”)

The only alternative seems to be that there are in fact two homophonous be verbs, and quotative “be like” makes use of both. Maybe this isn’t such a big deal. If I’m right about the diachronic process by which quotative “be like” arose, then we can at least see a two-step process: quotative “be like” was solely a stative predicate in its early use and for most of its early history; only later did it begin to be used as an eventive predicate. And if there are in fact two be verbs, the eventive sounds exactly like the stative and is in fact much rarer than the stative, so I suppose one can see how these facts laid the groundwork for the eventual use of stative “be like” as an eventive predicate.