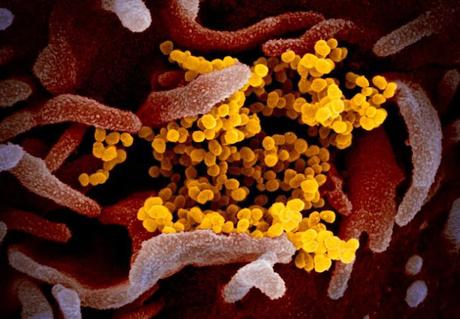

This scanning electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2 (yellow) among human cells (pink). This virus was isolated from a patient in the U.S. (Color has been added to the image to better show the virus and its environment.)

(Image: © NIAID-RML)

The image above of the Coronavirus is from livescience.com

A worldwide pandemic is going to happen again. Scientists and medical professionals have been warning us about that for decades now. It will happen because most nations have not adequately prepared to deal with such and occurrence -- and that includes the United States.

The question we currently face is whether the Coronavirus is that pandemic. It might be.

Here is just a part of what the editorial board of The New York Times has to say:

In December, another new virus — SARS-CoV-2 — made the leap from animals to humans. It has now infected more than 83,000 people across more than 50 countries. Nearly 3,000 people have died, most of them in China where the outbreak began. Global health experts are once again sounding the alarm. It’s unclear how bad things might get this time around. Covid-19, the disease caused by this new virus, appears to be between seven and 20 times more deadly than seasonal flu, which on average kills between 300,000 and 650,000 people globally each year. But that fatality rate could prove to be much lower, especially if it turns out that many milder cases have evaded detection.

In the meantime, this much is not in dispute: SARS-CoV-2 spreads easily — more easily than SARS or seasonal flu — and is tough to detect. It’s the kind of virus that would be extremely difficult to contain even in a best-case scenario, and the world is hardly in a best-case scenario now. Rising nationalism, waning trust and lingering trade wars have undermined cooperation between global superpowers. Rampant misinformation and growing skepticism of science are imperiling public understanding of the crisis and governments’ response to it.

In the United States, a coming general election has politicized what should be a clear public health priority. On Tuesday, Dr. Nancy Messonnier, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, warned that a global pandemic was all but inevitable and asked the American public to brace itself for impact. That same day, her boss’s boss, President Trump, insisted that everything was well under control.

Mr. Trump has requested from Congress only $2.5 billion to address Covid-19 — far less than the $15 billion that experts say is needed. He has also made some curious personnel choices in recent days: putting Vice President Mike Pence in charge of the federal response, and muzzling Dr. Anthony Fauci, the long-serving director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Fauci has guided the nation through just about every outbreak and epidemic since 1984, and is widely recognized as one of the world’s foremost authorities on managing such crises. As governor of Indiana, Mr. Pence badly botched the response to an H.I.V. outbreak, which resulted in hundreds of preventable infections.

There is still a chance that Covid-19 will prove to be more fire drill than actual fire. A global pandemic is all but certain, but there are many unknowns: Will the virus itself prove to be less contagious or far less deadly than is currently feared? Will it show a tendency to recede in warmer weather the way that seasonal flu does? Can a vaccine be made quickly available? (Dr. Fauci says that one may be ready for testing in as little as two months, and could be commercially available in about a year.) Any of these developments may yet break the global transmission chain, and the vortex of fear and market-tumbling anxiety in which the world now finds itself may yet pass.

If the next few weeks or months bring calm — and scientists increasingly worry that they will not — the world would do well to remember this time what it seems to have forgotten again and again. Another pathogen will emerge soon enough, and another after that. Eventually, one of them will be far worse than all its predecessors. If we are very unlucky, it could be worse than anything in living memory. Imagine something as contagious as measles (which any given infected person passes to 90 percent of the people he or she encounters) only many times more deadly, and you’ll have a good sense of what keeps global health officials up at night.

Here’s what is certain: Despite many warnings over many years, we are still not ready. Not in China, where nearly two decades after that SARS outbreak food markets that sell live animals still thrive and authoritarianism still undermines honest and accurate communication about infectious diseases. Not in Africa, where basic public health capacity remains hobbled by a lack of investment and, in some cases, by political unrest and violence. Not in the United States, where shortsighted budget cuts and growing nationalism have shrunk commitments to pandemic preparedness, both at home and abroad.

To be sure, some broad progress has been made in the past few years. Vaccine development and deployment now proceed faster than at any point in history. The World Health Organization has corrected many of the institutional shortcomings that thwarted its responses to previous outbreaks. Other countries, in both Europe and Africa, have stepped up to fill the global health leadership position that America appears to have vacated.

But, as Covid-19 makes clear, much more is still needed.

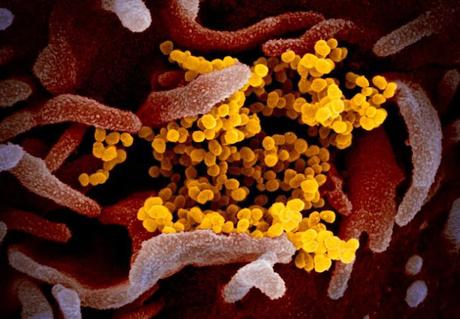

This scanning electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2 (yellow) among human cells (pink). This virus was isolated from a patient in the U.S. (Color has been added to the image to better show the virus and its environment.)

(Image: © NIAID-RML)

The image above of the Coronavirus is from livescience.com

A worldwide pandemic is going to happen again. Scientists and medical professionals have been warning us about that for decades now. It will happen because most nations have not adequately prepared to deal with such and occurrence -- and that includes the United States.

The question we currently face is whether the Coronavirus is that pandemic. It might be.

Here is just a part of what the editorial board of The New York Times has to say:

In December, another new virus — SARS-CoV-2 — made the leap from animals to humans. It has now infected more than 83,000 people across more than 50 countries. Nearly 3,000 people have died, most of them in China where the outbreak began. Global health experts are once again sounding the alarm. It’s unclear how bad things might get this time around. Covid-19, the disease caused by this new virus, appears to be between seven and 20 times more deadly than seasonal flu, which on average kills between 300,000 and 650,000 people globally each year. But that fatality rate could prove to be much lower, especially if it turns out that many milder cases have evaded detection.

In the meantime, this much is not in dispute: SARS-CoV-2 spreads easily — more easily than SARS or seasonal flu — and is tough to detect. It’s the kind of virus that would be extremely difficult to contain even in a best-case scenario, and the world is hardly in a best-case scenario now. Rising nationalism, waning trust and lingering trade wars have undermined cooperation between global superpowers. Rampant misinformation and growing skepticism of science are imperiling public understanding of the crisis and governments’ response to it.

In the United States, a coming general election has politicized what should be a clear public health priority. On Tuesday, Dr. Nancy Messonnier, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, warned that a global pandemic was all but inevitable and asked the American public to brace itself for impact. That same day, her boss’s boss, President Trump, insisted that everything was well under control.

Mr. Trump has requested from Congress only $2.5 billion to address Covid-19 — far less than the $15 billion that experts say is needed. He has also made some curious personnel choices in recent days: putting Vice President Mike Pence in charge of the federal response, and muzzling Dr. Anthony Fauci, the long-serving director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Fauci has guided the nation through just about every outbreak and epidemic since 1984, and is widely recognized as one of the world’s foremost authorities on managing such crises. As governor of Indiana, Mr. Pence badly botched the response to an H.I.V. outbreak, which resulted in hundreds of preventable infections.

There is still a chance that Covid-19 will prove to be more fire drill than actual fire. A global pandemic is all but certain, but there are many unknowns: Will the virus itself prove to be less contagious or far less deadly than is currently feared? Will it show a tendency to recede in warmer weather the way that seasonal flu does? Can a vaccine be made quickly available? (Dr. Fauci says that one may be ready for testing in as little as two months, and could be commercially available in about a year.) Any of these developments may yet break the global transmission chain, and the vortex of fear and market-tumbling anxiety in which the world now finds itself may yet pass.

If the next few weeks or months bring calm — and scientists increasingly worry that they will not — the world would do well to remember this time what it seems to have forgotten again and again. Another pathogen will emerge soon enough, and another after that. Eventually, one of them will be far worse than all its predecessors. If we are very unlucky, it could be worse than anything in living memory. Imagine something as contagious as measles (which any given infected person passes to 90 percent of the people he or she encounters) only many times more deadly, and you’ll have a good sense of what keeps global health officials up at night.

Here’s what is certain: Despite many warnings over many years, we are still not ready. Not in China, where nearly two decades after that SARS outbreak food markets that sell live animals still thrive and authoritarianism still undermines honest and accurate communication about infectious diseases. Not in Africa, where basic public health capacity remains hobbled by a lack of investment and, in some cases, by political unrest and violence. Not in the United States, where shortsighted budget cuts and growing nationalism have shrunk commitments to pandemic preparedness, both at home and abroad.

To be sure, some broad progress has been made in the past few years. Vaccine development and deployment now proceed faster than at any point in history. The World Health Organization has corrected many of the institutional shortcomings that thwarted its responses to previous outbreaks. Other countries, in both Europe and Africa, have stepped up to fill the global health leadership position that America appears to have vacated.

But, as Covid-19 makes clear, much more is still needed.

Politics Magazine

This scanning electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2 (yellow) among human cells (pink). This virus was isolated from a patient in the U.S. (Color has been added to the image to better show the virus and its environment.)

(Image: © NIAID-RML)

The image above of the Coronavirus is from livescience.com

A worldwide pandemic is going to happen again. Scientists and medical professionals have been warning us about that for decades now. It will happen because most nations have not adequately prepared to deal with such and occurrence -- and that includes the United States.

The question we currently face is whether the Coronavirus is that pandemic. It might be.

Here is just a part of what the editorial board of The New York Times has to say:

In December, another new virus — SARS-CoV-2 — made the leap from animals to humans. It has now infected more than 83,000 people across more than 50 countries. Nearly 3,000 people have died, most of them in China where the outbreak began. Global health experts are once again sounding the alarm. It’s unclear how bad things might get this time around. Covid-19, the disease caused by this new virus, appears to be between seven and 20 times more deadly than seasonal flu, which on average kills between 300,000 and 650,000 people globally each year. But that fatality rate could prove to be much lower, especially if it turns out that many milder cases have evaded detection.

In the meantime, this much is not in dispute: SARS-CoV-2 spreads easily — more easily than SARS or seasonal flu — and is tough to detect. It’s the kind of virus that would be extremely difficult to contain even in a best-case scenario, and the world is hardly in a best-case scenario now. Rising nationalism, waning trust and lingering trade wars have undermined cooperation between global superpowers. Rampant misinformation and growing skepticism of science are imperiling public understanding of the crisis and governments’ response to it.

In the United States, a coming general election has politicized what should be a clear public health priority. On Tuesday, Dr. Nancy Messonnier, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, warned that a global pandemic was all but inevitable and asked the American public to brace itself for impact. That same day, her boss’s boss, President Trump, insisted that everything was well under control.

Mr. Trump has requested from Congress only $2.5 billion to address Covid-19 — far less than the $15 billion that experts say is needed. He has also made some curious personnel choices in recent days: putting Vice President Mike Pence in charge of the federal response, and muzzling Dr. Anthony Fauci, the long-serving director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Fauci has guided the nation through just about every outbreak and epidemic since 1984, and is widely recognized as one of the world’s foremost authorities on managing such crises. As governor of Indiana, Mr. Pence badly botched the response to an H.I.V. outbreak, which resulted in hundreds of preventable infections.

There is still a chance that Covid-19 will prove to be more fire drill than actual fire. A global pandemic is all but certain, but there are many unknowns: Will the virus itself prove to be less contagious or far less deadly than is currently feared? Will it show a tendency to recede in warmer weather the way that seasonal flu does? Can a vaccine be made quickly available? (Dr. Fauci says that one may be ready for testing in as little as two months, and could be commercially available in about a year.) Any of these developments may yet break the global transmission chain, and the vortex of fear and market-tumbling anxiety in which the world now finds itself may yet pass.

If the next few weeks or months bring calm — and scientists increasingly worry that they will not — the world would do well to remember this time what it seems to have forgotten again and again. Another pathogen will emerge soon enough, and another after that. Eventually, one of them will be far worse than all its predecessors. If we are very unlucky, it could be worse than anything in living memory. Imagine something as contagious as measles (which any given infected person passes to 90 percent of the people he or she encounters) only many times more deadly, and you’ll have a good sense of what keeps global health officials up at night.

Here’s what is certain: Despite many warnings over many years, we are still not ready. Not in China, where nearly two decades after that SARS outbreak food markets that sell live animals still thrive and authoritarianism still undermines honest and accurate communication about infectious diseases. Not in Africa, where basic public health capacity remains hobbled by a lack of investment and, in some cases, by political unrest and violence. Not in the United States, where shortsighted budget cuts and growing nationalism have shrunk commitments to pandemic preparedness, both at home and abroad.

To be sure, some broad progress has been made in the past few years. Vaccine development and deployment now proceed faster than at any point in history. The World Health Organization has corrected many of the institutional shortcomings that thwarted its responses to previous outbreaks. Other countries, in both Europe and Africa, have stepped up to fill the global health leadership position that America appears to have vacated.

But, as Covid-19 makes clear, much more is still needed.

This scanning electron microscope image shows SARS-CoV-2 (yellow) among human cells (pink). This virus was isolated from a patient in the U.S. (Color has been added to the image to better show the virus and its environment.)

(Image: © NIAID-RML)

The image above of the Coronavirus is from livescience.com

A worldwide pandemic is going to happen again. Scientists and medical professionals have been warning us about that for decades now. It will happen because most nations have not adequately prepared to deal with such and occurrence -- and that includes the United States.

The question we currently face is whether the Coronavirus is that pandemic. It might be.

Here is just a part of what the editorial board of The New York Times has to say:

In December, another new virus — SARS-CoV-2 — made the leap from animals to humans. It has now infected more than 83,000 people across more than 50 countries. Nearly 3,000 people have died, most of them in China where the outbreak began. Global health experts are once again sounding the alarm. It’s unclear how bad things might get this time around. Covid-19, the disease caused by this new virus, appears to be between seven and 20 times more deadly than seasonal flu, which on average kills between 300,000 and 650,000 people globally each year. But that fatality rate could prove to be much lower, especially if it turns out that many milder cases have evaded detection.

In the meantime, this much is not in dispute: SARS-CoV-2 spreads easily — more easily than SARS or seasonal flu — and is tough to detect. It’s the kind of virus that would be extremely difficult to contain even in a best-case scenario, and the world is hardly in a best-case scenario now. Rising nationalism, waning trust and lingering trade wars have undermined cooperation between global superpowers. Rampant misinformation and growing skepticism of science are imperiling public understanding of the crisis and governments’ response to it.

In the United States, a coming general election has politicized what should be a clear public health priority. On Tuesday, Dr. Nancy Messonnier, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, warned that a global pandemic was all but inevitable and asked the American public to brace itself for impact. That same day, her boss’s boss, President Trump, insisted that everything was well under control.

Mr. Trump has requested from Congress only $2.5 billion to address Covid-19 — far less than the $15 billion that experts say is needed. He has also made some curious personnel choices in recent days: putting Vice President Mike Pence in charge of the federal response, and muzzling Dr. Anthony Fauci, the long-serving director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Dr. Fauci has guided the nation through just about every outbreak and epidemic since 1984, and is widely recognized as one of the world’s foremost authorities on managing such crises. As governor of Indiana, Mr. Pence badly botched the response to an H.I.V. outbreak, which resulted in hundreds of preventable infections.

There is still a chance that Covid-19 will prove to be more fire drill than actual fire. A global pandemic is all but certain, but there are many unknowns: Will the virus itself prove to be less contagious or far less deadly than is currently feared? Will it show a tendency to recede in warmer weather the way that seasonal flu does? Can a vaccine be made quickly available? (Dr. Fauci says that one may be ready for testing in as little as two months, and could be commercially available in about a year.) Any of these developments may yet break the global transmission chain, and the vortex of fear and market-tumbling anxiety in which the world now finds itself may yet pass.

If the next few weeks or months bring calm — and scientists increasingly worry that they will not — the world would do well to remember this time what it seems to have forgotten again and again. Another pathogen will emerge soon enough, and another after that. Eventually, one of them will be far worse than all its predecessors. If we are very unlucky, it could be worse than anything in living memory. Imagine something as contagious as measles (which any given infected person passes to 90 percent of the people he or she encounters) only many times more deadly, and you’ll have a good sense of what keeps global health officials up at night.

Here’s what is certain: Despite many warnings over many years, we are still not ready. Not in China, where nearly two decades after that SARS outbreak food markets that sell live animals still thrive and authoritarianism still undermines honest and accurate communication about infectious diseases. Not in Africa, where basic public health capacity remains hobbled by a lack of investment and, in some cases, by political unrest and violence. Not in the United States, where shortsighted budget cuts and growing nationalism have shrunk commitments to pandemic preparedness, both at home and abroad.

To be sure, some broad progress has been made in the past few years. Vaccine development and deployment now proceed faster than at any point in history. The World Health Organization has corrected many of the institutional shortcomings that thwarted its responses to previous outbreaks. Other countries, in both Europe and Africa, have stepped up to fill the global health leadership position that America appears to have vacated.

But, as Covid-19 makes clear, much more is still needed.