Anti-corruption suggestion box in kenya (Source: Flickr user lauren_pressly)

Transparency International last week released its annual report, which suggests that Kenya is losing the battle against corruption. According to the report, Kenya ranked 154 out of 182 countries surveyed, indicating that both Kenya and Zimbabwe, who are tied, are at the bottom of the scale of countries worldwide combating corruption. The plague of corruption in developing countries has consequences. Corruption scares away foreign direct investment, creates poverty, leads to unemployment, limits the ability of governments to raise tax revenue, results in a misallocation of resources, poor economic development, and a lack of competition. Against a 19% inflation rate and high unemployment, Kenya can little afford the consequences of corruption.

Studies that measure public perception of corruption are a useful tool in comparing anti-corruption efforts (or the lack thereof) across countries, but they do not provide actionable data to combat corruption. In Kenya, the Center for Private Enterprise (CIPE) and its partners have recently tried a different approach. The Kenya City Integrity Project does not measure the level of corruption in Kenya. Instead, it looks at measures to prevent corruption and how effectively those measures have been implemented. And it does so at the city, rather than the national, level – the level where most corruption actually takes place.

Last week the CIPE, Global Integrity, and the Kenyan Association of Manufacturers hosted a series of roundtables in Kisumu, Mombasa, and Nairobi for Kenyan stakeholders from civil society, local government, and the private sector to discuss the study, which was conducted by four Kenyan research organizations in August 2011. As a new kind of corruption “scorecard,” the study covered transparency, anti-corruption, and accountability efforts in Kenya’s three largest cities, which contribute about 80% of Kenya’s GDP. The purpose of these roundtables was to engage all stakeholders in developing specific recommendations that the government could act upon to improve service delivery and minimize corruption.

The report is the first ever attempt at the city level to understand whether relevant anti-corruption laws exist and whether they are being properly implemented. It is also unique in its depth, covering 177 different indicators. In an effort to understand the key governance and anti-corruption mechanisms that already exist, the study focused on systems that govern city elections, media freedoms, how city governments resolve conflicts of interest, city fiscal and budgetary management, and city administration and business regulations. This report answers the key questions on whether citizens have access to city government, whether citizens effectively monitor government services, and whether citizens can freely and effectively advocate for reforms.

The three city assessments do not seek to measure the extent of corruption but rather to understand the medicine applied to combat corruption: the public policies, institutions, and practices that deter, prevent, or punish corruption. The research was conducted by three Kenyan firms that understand the Kenyan realities – including the Kenyan Association of Manufacturers and Hakijamii Haki Yetu, the Civil Society Organization Network – utilizing Global Integrity’s award winning research methodology.

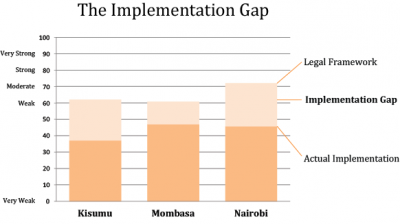

Unfortunately, the study found that all three cities need to do a much better job implementing existing laws. Kenyan cities have policies and regulations in place that should allow for transparency and accountability in governance. However, although laws exist, they are not properly implemented. One of the quickest and most effective solutions to corruption in these cities would be for the city administrations to implement existing laws. The reality is that solutions combating corruption are often much more complicated than they appear.

Source: Kenya City Integrity Project

In Kisumu, the study found, the media has the freedom to report on corruption cases without fear of intimidation. City elections for the most part are free and fair. There are regulations in place that are being implemented on public procurement of goods and services and there are frequent audits of government purchases. In order to potentially reduce corruption the city needs to create regulations to enforce asset disclosures so that the electorate can determine who is financing the political candidates. There are no codes of conduct governing the city’s executive and legislature. This means that any conflict of interests between city officials and the provision of services cannot be properly enforced. Finally, the city needs to integrate the work of different departments as part of a comprehensive strategy to develop the city, provide services, and attract investment.

The District Commissioner of Kisumu, Mr. Mabeya Mogaka suggested that “all stakeholders focus on hope. Changes are being implemented that include a 14 day requirement that all public officials respond to inquiries in writing. While this report was conducted in August, since then the city has elected new officials and we must give them time to assess what is going on and implement change. This requires that all of us government, civil society, and the private sector work together.”

Mombasa’s strengths include its efficiency in managing public finances, disclosing budgets, collecting taxes, and auditing city expenditures. The researchers spoke highly of the city procurement system for goods and services, but there is ambiguity in how tenders are awarded. Although systems exist, the research revealed that a select few companies or individuals are often the beneficiaries of public tenders. Another weakness is the hiring process for public officials. Civil service positions are advertised in local papers, but the selection process is not very transparent. Although Mombasa has embarked on several development projects, political patronage seems to dominate where projects are implemented. Although journalists are aware of corruption few stories actually make it into the paper as editors block certain stories for fear of losing advertising revenues.

Finally, Nairobi’s strengths include free and fair elections, excellent management of taxation and city audits, and the effective public administration and business administration systems that the city has put into place. Unfortunately, local businesses complain about the poor quality of service delivery in Nairobi even after paying taxes. Many businesses feel that the enforcement of city’s laws and regulations is selective and that there are not forums in place for business to provide input on policies or budget decisions. A business faces burdensome licenses and regulatory approvals and although citizens pay taxes, the quality of services remains poor.

Over the coming months, KAM and the local researchers will present the report to government and civil society along with concrete recommendations that include further engagement, enforcement of existing laws, creation of “one-stop-shops” for licenses and tax payments, and a proposal that high-ranking civil servants sign a voluntary code of ethics.