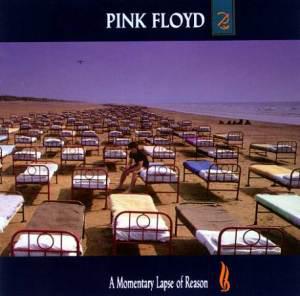

One slip, and down the hole we fall

It seems to take no time at all

A momentary lapse of reason

That binds a life for life

A small regret, you won’t forget,

There’ll be no sleep in here tonight [1].

Violence is seldom out of the soccer news in Italy. The story of 2011 was the improbable self-fashioning of Andrea Agnelli as a populist ringleader—a move considered to be necessary, along with a substantial helping of hype, for a full restoration of Juventus FC after what now appears, widely yet not uncontroversially, as a ruthless and hasty brush of restorative ‘justice’ by the legal authorities in the country—but now the fans of Genoa have invaded the field a few days ago, demanding the grifoni players to strip off their jersey as to set in motion a lurid machinery of protest. (As usual, Italian football managers take their time in marking a clear distance from the ugliest and most eccentric manifestations of their supporting fans, whether these involve a showdown between warlords or a sheer episode of racism.)

No sooner had this shameful excitement died down that the familiar, long-running saga of rage and violence is back in the headlines. At a nervy 2-2 draw at home with Novara, which was as alarming as the overall season of both teams involved, the coach of Fiorentina, Delio Rossi, substituted the attacking midfielder Adem Ljajic for poor performance. Ljajic is a Serbian born to Bosnian parents who was once on trial for Manchester United and who did not exactly spend 32 minutes of the game prospecting for his own change, especially after he had enjoyed more playing time under Mihajlovic. He saw it fitting to reply with a sarcastic hand-clap and two thumbs up. Samples of these taunting intentions, extracted from a mental recess several inches behind the sumptuously frescoed images of the subsequent TV broadcast, have plunged Delio Rossi into the black pigment of rage, some flakes of which may be red lacquer, as he launched down to the dugout and repeatedly attempted to punch the young player in the face. (As a consequence of his physical assault, whose substantial madness is shocking, Rossi has been fired and received a three-month ban—a suspension that will very nearly cost his coaching career.)

For weeks and maybe months this gruesome fragment will be seen, studied, reviled and admired. ‘Go up the stairs of the Sala Grande,’ Antonfrancesco Doni wrote to a friend visiting Florence, ‘and take a close look at a group of horses and men, a battle-scene by Leonardo da Vinci, and you will see something miraculous.’ When he expressed his touring advise, in 1549, the Venetian Doni had in mind Leonardo da Vinci’s lost mural The Battle of Anghiari, which was commissioned by the Florentine republic for the council hall of the Palazzo della Signoria to celebrate in suitably triumphalist terms a famous victory of Florence against the Milanese. As it was typical of his morphing style, the assignment required Leonardo an extensive study of military engineering, fresco techniques, and a journey into a universe of putrefaction and corporeal sickness: wounds and emaciation, riffs across the darkening plains of flesh, mass gone wrong and solidity petrified. Indeed, the vicious nature of war that was the centerpiece of the mural, with its harrowing tableaux of terrified horses and soldiers folding into each other as paint and brush wanted them to do, might not have been quite what the Signoria had in mind—and neither was this season of the Viola in Serie A supposed to reveal the ugliness of the soccer war.

The great hall on the first floor of the Palazzo in Florence, the whole 2000 square meters of it, is quite different from Leonardo’s original intentions [2]; the room as we now see it is the result of Giorgio Vasari’s intervention, who began extensive remodeling and redecoration in 1555 and by the mid-1560s had Leonardo’s own Battle of Anghiari disappear, perhaps as a protective measure, under a makeover fresco on the same topic painted by himself. But what is the nature of that disappearance? Does it mean, as the football legislators assumed once a period of hooliganism was over, that the violence was demolished and therefore irrevocably lost? Or was it perhaps merely hidden from view, covered over, ambiguously flickering as if through Vasari’s idiosyncratic way of ‘preserving’ a masterpiece? And especially, in the sense that these questions are substances rather than theories or conjectures, are any of the similarities between the coaching men agitating on the bench and the sixteenth-century Florentine painters working on top of a custom-built scaffold on wheels discernible at all?

Now in his early fifties, Delio Rossi is a quiet-spoken man, but his demeanor belies a steeliness which must have kept him at his technical quest through periods of failure and isolation. Leonardo would appreciate this quality, his obstinate rigor, as he would have also enjoyed all the high-tech machinery being used by soccer bloggers: heat maps, chalkboards, miniature endoscopic cameras, reflectographs, tactical looms and radar. (I sometimes wander about Leonardo applying for a Ph.D. at UC in San Diego and carving a plan of study ranging from the forensic to the military, including at least archeology, medicine, biochemistry and of course art history.) A self-styled and streetwise diagnostician from Rimini, Rossi is an awkward maverick of the 4—3—3 formation among the cabals of the Italian soccer establishment.

Even though details of his activity are minutely documented, mostly at Palermo, one piece of basic information is maddeningly absent or equivocal: where did he get the idea that prevailing attacking schemes in the Serie A needed to be reformed. The only evidence is that Rossi is a huge admirer of Zeman. Anyone who is familiar with the history of Italian soccer will recognize the scale of the problem; those associated with the Tuscan school of coaching, Giuseppe Papadopulo or Renzo Ulivieri, turned out to be some among the most tantalizing and fiercely debated figures ever to sit on a bench—impossible to extricate from a panorama of villains and turbulence similar to the Battle of Anghiari, when you inspect the upper reaches of Leonardo’s scaffold.

Vasari’s means of preserving his predecessor’s mural might have had something to do with the use of pockets of air as a deliberate protective devise. Behind Rossi’s inexcusable punching madness it is a tactical preference to emerge scathed. Most pressing: what state is the 4—3—3 in? On the score of Roma’s failing implementation alone, there are grounds for pessimism. Even before you consider Mourinho’s joyless triumph at Real Madrid, Antonio Conte’s shuffle of underdrawings (some wonderfully propulsive, some affected by poor finishing) at Juventus and Massimiliano Allegri’s steam-punk exaggeration (some fairly routine, some almost miraculous), the three-striker formula is in bad condition. Judging from Wenger’s insistence on the rotating midfield, you can liken the 4—3—3 coach to a fresco specialist who wants to operate with an oil-mixture that would allow him to study the microscopic particles of his work as he goes along. And, after all, aren’t coaches like Renaissance artists in their obsession to guard their own recipes for paints and glazes? Aren’t their gesticulating assistants on the side line, famously expert at mixing medicinal cocktails, like apprentices in a workshop, grinding colors for the master? Strip Rossi’s humiliation of its emptiness, of its flattery too, and a sticking vitriol would appear as calcio’s current legacy. ♦

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Notes.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[2] As Charles Nicholl reminds us on The London Review of Books, the mayor of Florence, Matteo Renzi, and the US National Geographic Society, which presented a powerful financial back-up in return for exclusive rights to the story, are trying to lobby for a removal of Vasari’s frescoes to explore what remains of Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari.