Ergo, the self-reflexivity of his 1996 film A Moment of Innocence takes on a more personal note than the usual film-about-film structure. Makhmalbaf is not only making a film about the process of making a film, he's doing so for a film that tells the story, essentially, of how he came to cinema. It also serves as a means of atonement, for the project arises when the policeman he stabbed, now 20 years older and retired, comes to the director's home asking to be an actor.

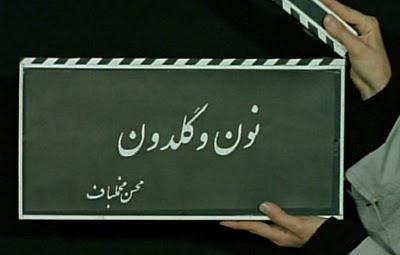

Announcing the reflexive nature of the film are the opening credits, written on a clapperboard and read aloud by the loader as if setting up each take. Makhmalbaf holds auditions for the young version of himself while the assistant director, Zinal, works with the policeman to help cast his own doppelgänger. Makhmalbaf finds his actor quickly, collecting a group of young men and grilling them on their politics until he finds one who displays the same rebellious streak he himself displayed as a young man. The ex-cop, meanwhile, arranges his potential actors in what looks like a police lineup, merely searching for the one who looks most like him. Wryly, Makhmalbaf illustrates the different mindsets between the artist and someone used to being the audience. How many times have people praised a biopic performance because the lead looks just like the film's subject? Hilariously, though Makhmalbaf wants to set things right by letting the policeman tell his story, as an artist he cannot abide such a simplistic means of cast selection and insists upon an actor who aligns with the cop emotionally, not physically.

This action inflames the tension between the cop and the man who stabbed him, and the policeman stomps off to return to his hometown in Orumieh as Zinal chases after him. By this point, it has become clear that we were not merely watching footage of the audition process but that this is the movie. The fact that a camera monitors Zinal and the cop walking at all makes for an obvious clue, but just to hammer home the point, Makhmalbaf uses audio so crisp it sounds no different than the material he got in the studio where he held auditions. At last, Zinal convinces the policeman that he can coach the young actor chosen by the director to faithfully relate what happened to him, and the cop takes the kid under his wing to immerse the boy in his memories.

A Moment of Innocence is primarily concerned with memory and perspective. The policeman remembers every detail of the incident, as it has haunted him for 20 years. He wants the young actor to understand everything about who he was and how he felt to ensure his story gets told accurately. The policeman instructs the actor playing him on proper officer decorum, the surrounding area of his old post and the emotional process of falling in love with a woman to whom he wanted to give a flower before Makhmalbaf stabbed him and the man never saw her again. He works from deeply ingrained memory.

Makhmalbaf, meanwhile, admits to having scattered memories of the event, having changed so much in the intervening time. He knows only what happened and the basics of why he did what he did. His approach to the actor playing himself is simply to address the young man as if he were the young Mohsen, never breaking even as he offers advice and instructions. Unable to remember the event clearly himself, he molds the actor into himself in the hopes of unlocking that mindset he abandoned 20 years ago.

By committing so fully to blurring the line between himself and the actor, Makhmalbaf blends his desire to set things right and to link his past to his present, which he of course must do through cinema. A Moment of Innocence not only references itself throughout, it also incorporates all of cinema into its structure. The Iranian humor of people always getting lost on their way to destinations can be seen at the start, as the cop first comes to the wrong house, then arrives at Makhmalbaf's with only his child daughter home. Later, the policeman takes the young policeman to the tailor who used to make his uniforms, and the old man lights up when he finds out they're making a movie. He remembers all the Western movies he watched back when the shah was in power, gushing over Kirk Douglas and John Ford movies. He even made costumes for actors. The film itself recalls the self-reflexive nature of Abbas Kiarostami's Close-Up, which directly involved Makhmalbaf as the director impersonated by a film-loving con man. Kiarostami's movie dealt with the way art can save people; A Moment of Innocence shows how it can also make them forget what they needed saving from.

The pull of cinema appears to suck in those who might not even want to be in the film. As the policeman wistfully remembers the woman he thinks about daily, Makhmalbaf reveals to his doppelgänger that the woman was not only his cousin but accomplice in securing the cop's firearm. They travel to the cousin's house, but she does not want to be in the film, ashamed of her radical past. Makhmalbaf asks to use her daughter as her younger self, but the woman wants nothing to do with the film. The daughter, however, walks out to give tea to the young man, who politely refuses (his response that he does not drink tea lining up with the director's own). Suddenly, the girl slips into the role of her mother, and she and the young man start discussing plans to get the cop's gun. Iranian directors make use of non-actors more than anyone since the Italian neorealists, and here it seems as even those who might not want to be in a film cannot fight the universal truth that we are all of us actors.

At only 78 minutes, A Moment of Innocence might seem overstuffed, what with its corkscrewing narrative always falling into a new cycle just when everything seems settled. As the cop instructs the young policeman how he held the flower and told the girl the time when she stole his heart, a girl walks by and innocently asks for the time. Later, we learn that the girl was the one playing the young cousin, and she inadvertently asked the other actor the time without knowing who he was. The policeman, also unaware of all that just happened, is ecstatic. "It happened just like that!" he enthuses. When the time comes to film the scene, however, the policeman has learned of the real woman's connection to Mohsen, and when the young actress walks up and asks the time, the old man leaps out and asks if she is with young Makhmalbaf. When she confirms this, he flies into a rage, conflating the actress playing the woman with the actual woman and interpreting her response as confirmation from the "horse's mouth" that she was always in league with the man who sent him adrift for two decades. In his fury, he tells the young man to change events, to draw his gun and shoot the woman when she approaches as if killing her in a film might send him back in time to avoid 20 years of pain.

Amazingly, such dense developments do not break the film's slim running length. Makhmalbaf finds ways of always maintaining interest, and he even draws narrative suspense from the behind-the-scenes structure. A funeral passes by the policeman, young cop and Zinal and the two old men walk with it to pay respects. The young man also tags along, setting down the flower. When he returns, the plant is gone, and his frantic tear down the alleyways looking for the person who took it carries a hefty suspense considering the puny flower is transparently just a prop.

With its conflicting perspectives fleshing out both sides of the story but muddying a clear progression of events, A Moment of Innocence recalls Rashomon, but instead of both characters trying to absolve themselves they want merely to make the other understand how he felt. Slowly, the actors begin to exhibit not the feelings of the director and cop's younger selves but of their current mindsets. Mohsen needs the young man to reflect his old radical hostility, while the cop, for all his lingering anger, still wants to know what would have happened if he could have asked that girl out. But the young cop wavers between the flower and the gun, as torn as the actual policeman, while the young Makhmalbaf suddenly breaks down when rehearsing the stabbing, sobbing that he cannot kill a man and that surely he could save the impoverished people of Iran some other way.

The film culminates in the shooting of the incident that defined both men's lives, but as the tension mounts from close-ups of the young cop's hand on his pistol grip and a piece of bread draped over the knife in young Mohsen's hand, something remarkable happens. At the last second, both actors change their minds, the cop handing the girl the flower instead of shooting and the young Mohsen handing out the bread instead of the knife. The film freezes on the symbolic image, and the improvised action by the two young men displays the true desires of the actual people involved and visualizes an atonement for past and present anger. It may be the most powerful freeze-frame I've seen in a film, beating out even the finale of Close-Up, in which Makhmalbaf helped facilitate another reconciliation. Not only does the image make peace between the two men, it unites the people of Iran, pro- and anti-shah, in nonviolent, empathetic terms. It is a unifying vision of the Iranian people beyond politics and nationalistic identity. No wonder the country's government banned it.