Thinking about golf and trying to master it takes one’s mind away from other troubles.– William Benzon

I think a lot about golf as a metaphor for life. The harder you swing, the less far it goes.– Paul Fireman

That’s the clubhouse for Liberty National Golf Course, on the banks of the Hudson River – or is it the upper end of New York Bay at that point? – at the south end of Jersey City, NJ. When you go up the steps, which are chained off midway, you go onto the club grounds which are, of course, private. When you go down, you come to the club’s private pier. You can see the Statue of Liberty at the left edge of the photo, hence the club’s name:

The pier is for a motor launch that ferries club members back and forth to Manhattan. Club members with helicopters can land on the club’s helipad.

* * * * *

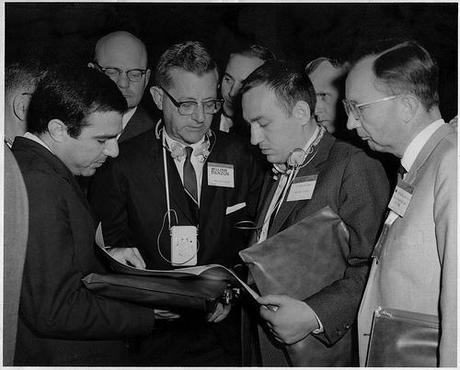

The man left of center in the photo below is my father:

I don’t know exactly what meeting this was, or when it took place. But it would have had to do with coal preparation in some way and it probably took place in the 1960s – the date on his badge appears to be 1966. He worked with Bethlehem Mines, the mining subsidiary of Bethlehem Steel (now defunct), and was Superintendent of Coal Preparation. He was in charge of removing impurities from coal so it could be used in smelting iron ore into iron. He has a few patents to his name and was quite distinguished in that field.

He was also an avid golfer. In 1962 he was in Europe on business – the Netherlands most likely – and managed to get in a trip to Scotland where he played two rounds on the Old Course at St. Andrews, one of the oldest in the world and the mecca of golfing.

At the upper right you see the two tickets from those rounds. The Old Course is public, so anyone can buy a ticket and play a round or two. I’m pretty sure the business card at the upper left is for the caddy my father hired for the day. He probably told me something about Mr. Crisp, but I don’t remember anything. Obviously Mr. Crisp would have the course well; more than likely he knew how read his golfers as well.

Then we have my father’s scorecards for the two rounds. He shot 89 for the first round, 16 over par, which was 73. Most courses are par 72. He improved by eight strokes for the second round and shot 81.

That’s pretty good. For many amateurs the goal is to break 90. During that period, the middle of his life, he rarely shot over 90 and for at least a decade he had a single digit handicap.

If you play golf, or at any rate if you know the game, then you know what all that means. Otherwise you may think it an odd game for grown men to whack a ball around a rather large garden space and attempt to get it in the hole. “Par” is just an odd word, though “handicap” is meaningful enough, but perhaps not in quite the golfer’s sense.

* * * * *

I’ll get around to that in due course, but I want to return to Liberty National. It’s built on a landfill. Jersey City has a gritty past as a port city, railroad terminus, and some industry. Most of that’s gone now. The shore has been reconstructed with high-rise offices and apartments downtown, a wonderful state park adjacent to the Statue of Liberty, and most recently, Liberty National.

It was the brainchild of Paul Fireman, who was Chairman of Reebok when he decided to build the course. This is the ninth course he’s built:

The owner said he is pleased. “It was never about making money, not that I wanted to lose money,” he said. The club itself, after stalling during the recession, now has 175 members, with a current full initiation fee of $250,000, and could top out at 250 members or so next year, Fireman said. The average member age is a surprisingly young 42. He said he expects a residential tower near the clubhouse, a delayed part of the original plan, to break ground within a year. “If that plays out like we hope it will and I break even on the whole thing, I'd be thrilled.”Fireman sounds like a man with whom my father would have enjoyed a round or two of golf. Like my father he understood the game’s moral dimension.

Fireman, 69, fell in love with the game as a boy in Brockton, Mass., a small, blue-collar city 25 miles south of Boston. The club where he caddied, Thorny Lea, had an unusual charter requiring a third of the members to be Catholic, a third Protestant and a third Jewish, he said. He was taken under the wing of a Massachusetts state amateur champion named Ed “Smiley” Connell, who showed him respect even as a kid caddie.

“My experience there at Thorny Lea was the strongest, most fundamental thing in my life, even more than parental,” he said. “I thought that golf had integrity, so I wanted my life to have integrity. And it showed me the value of respect and mutuality among people, that no one should be treated differently.” He said he abhors cliques and snobbish behavior in golf—even at clubs with $250,000 initiation fees—and that he tried in his business life to embrace and empower people from all walks of life.

* * * * *

The game’s peculiar scoring system is an aspect of that. I don’t know what the history is, whether it’s been scored that way from the beginning or whether the system evolved over time.

Here’s how it goes. The course has eighteen holes. Each hole is assigned a par value, the number of strokes a good player needs to hit the ball from the tee to the hole. Once the ball is on the green, two strokes are allowed to sink a put. Depending on the distance from the tee to the green, one, two, or three strokes are allowed to get from tee to green. So, individual holes are designed to require three, four, or five strokes – by a good player, a very good player. And the course as a whole is designed to require 72 strokes, though a few courses are a bit longer, and a few are a bit shorter.

When you shoot a round of golf you get a score, the number of strokes it took you to play the course. When you play a match, the player with the fewest strokes wins the match – that’s the most common scoring system, but there are others. Imagine, however, that you habitually play with people who are much better, or much worse, than you are. Either you’re going to loose all the time, or win all the time. Neither is much fun, though winning all the time is probably better, even if it’s boring.

That’s where the handicap figures in. A player is assigned a handicap based on their performance over a number of games – I don’t know the formula, but that’s a secondary matter. The idea of the handicap is to normalize your score to par. Let’s say you have a 15 handicap and you shoot 86. You subtract 15 from 86 and get 71. Not bad. And you just might beat your buddy who’s a better golfer, but only has a handicap of 7. If he shoots 79 or more, you’ve got him, though that 79 is better than your 86.

The handicap system allows people of different absolute abilities to compete with one another in a way that any one of them has a chance of winning the round. It is, if you will, an egalitarian feature of the game. Professionals, naturally, do not use handicaps. Professional matches are won on the basis of absolute scores, not normalized scores.

Just why this system evolved, I don’t know. If I had to guess, I’d guess it’s a side effect of the game’s aristocratic past. There aren’t that many dukes, earls, and barons in the world, not to mention princes and kings, and they tend to be spread out a bit in geography. So the gentleman golfer in times past is not likely to have a wide selection of playing companions. The handicap system lets a small group of players compete among themselves on a more or less even basis.

* * * * *

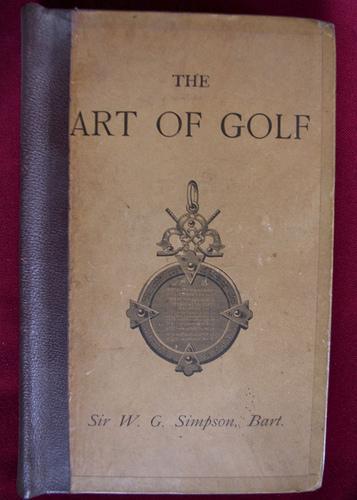

That, of course, is what’s known as a just-so story. But the game’s aristocratic past is not. One of the oldest books about the game, though not THE oldest, is The Art of Golf, by Sir W. G. Simpson, Bart. The “Bart” isn’t a name; it’s a title: Baronet. Sir Walter was a 19th Century Scottish lord who was something of a raconteur and sportsman; his father, who first got the title, was a surgeon who’d discovered chloroform. Here’s a shot of my father’s copy of the first edition:

The binding is not original, which lowers the value somewhat, not to mention the family crest (Danish, from the 17th Century) my father stamped on the title page and on page 13–a practice my father took from his father.

Sir Walter was also a friend of Robert Louis Stevenson, who provided an epigraph for the book: “Pleasures are more beneficial than duties, because, like the quality of mercy, they are not strained, and they are twice blessed.” Notice the allusion to Shakespeare. I don’t know whether Sir Walter took that line from something Stevenson had published or whether Stevenson composed it expressly for him.

It doesn’t matter. The point is that Sir Walter is the sort of fellow who’d deck out a book on golf with such literary appurtenances, not to mention the sort of droll wit on display in his brief whiz through the golf’s history, in which he notes, as I quoted in this post, that

Most probably a game so simple and natural in its essentials suggested itself gradually and spontaneously to the bucolic mind. A shepherd tending his sheep would often chance upon a round pebble, and, having his crook in his hand, he would strike it away; for it is as inevitable that a man with a stick in his hand should aim a blow at any loose object lying in his path as that he should breathe.What a crock! And Simpson knew it too, which is why he wrote it in the first place.

The real topper, though, is in Simpson’s absurd dedication:

To The Honourable Company Of Edinburgh Golfers This Book Is Dedicated Humbly As A Golfer Proudly As Their Captain Gratefully For Merry Meetings And Cordially Without Permission By The Author.The “Honourable Company” is not some high-flown name good old Wally used to designate his golfing chums. According to the Wikipedia it’s “the oldest verifiable organised golf club in the world” and which gave forth with the rules of golf in 1744. Wally was captain of the club, making him, if not the King of Golf, at least Prince of the Realm. And what’s with the “Cordially Without Permission”?

Now, though I don’t actually know this, I’m just guessing, but I’d bet that good old Wally would have had second thoughts about playing a round with Paul Fireman. Why? Because Fireman is Jewish. It is all well and good to play a game the scoring of which evens play among gentlemen. But there are limits, otherwise what’s the point of being a gentleman?

I’m not sure what Simpson would have said about playing a round with my father either. Though dad had a family crest, he had no title to go with it, but then Robert Louis Stevenson, whom Simpson knew from school days, didn’t have a title either. Stevenson did, in time, have fame, but not by the time Sir Walter put his initials at the front of his golf treatise.

* * * * *

My father loved Stevenson’s writing as well, and had a number of his books on the shelves, along with Dickens, Rafael Sabatini, Rider Haggard, Captain Marryat, Herman Melville, Mark Twain, an Encyclopedia Americana and a hundred or more books about golf. He studied the game, my father did, and kept notebooks on his play. One winter he painted some golf balls with red nail polish and went out to practice in the snow. He did that as much for the sheer whimsy of the thing as out of a need to hit some balls, though the need was real enough.

I don’t know just when he took up the game, though he didn’t play it as a child, as Fireman did. He was something of an athlete in his youth, fencing, football, gymnastics, and bicycle riding. But he didn’t take up gold until his early adulthood. Perhaps he took up the game because his father had taken it up, or perhaps he took it up when he joined Bethlehem Steel, which was a golfing company. One of the things he passed down is this golf club, which had belonged to Charles Schwab, one of the founders of the company:

Still, if that’s why he took up the game, the fact is that it is the game itself that fascinated him. He had little interest in country club socializing and in golf as a vehicle for business camaraderie.

I vaguely remember attending a Christmas party at Sunnehanna Country Club when I was a child; I seem to remember that they had a magician for entertainment. But that’s about all I remember of Sunnehanna, which was the “best” golf club in Johnstown at the time.

I know dad was happy when a club started up in Windbur, which was closer to home. But it wasn’t simply the closeness. Precisely because it was new, Windbur wasn’t so tied to a social and business scene that didn’t interest him.

I caddied for dad the day he won the club championship.

Tiger Woods may well have helped popularize the game and so relieved it of some of its elitist image. But there was no Tiger Woods in the 1950s and 1960s, when, as a child, I watched my father play, much less twenty years earlier when my father learned the game.

My father was no elitist. But he was certainly aware of golf’s complex relationship to power and privilege.

Which is why I pose the question: What would my father think of Liberty National? I’m sure he’d love to play the course, which by all accounts is a fine one. He’d love the views of New York Bay, and the City (where his father lived for many years and worked as chief engineer for the main Post Office). And, as I said above, to the extent that I can gauge Fireman’s character from what little I’ve read, I think enjoy playing golf with the man.

But $250,000 as an initiation fee? No way, Jose, no way. It’s all that money in a few hands, undoubtedly very capable hands in a way, that’s got me thinking. I’m sure dad would think about it too.

* * * * *

Let me tell you a story. Rather, let my father tell one. He was in the coal business. The coal business is dirty and dangerous. Men loose their lives mining it. The cleaning plants are noisy and the machinery, like all large machinery, is dangerous.

This is from a letter dad wrote to me in December of 1986:

One small incident gave me great satisfaction, not in my role of technician but in my role as supervisor. We had built a jig washing plant at Barrackville, near Morgantown, West Virginia. An electrician named John DeBolt was made foreman. He liked that, he liked me. He didn’t have to take crap from his former boss. His new boss [my father] was in the home office.

One night John called me about 10 pm. The plant was down, the jig wouldn’t work. I tried to help him with suggestions, but he had to try to work out the problem. I went to bed but could not sleep. I got up, dressed and left Johnstown at 2 am.Here’s what I want to know: How many of the men and women who are members of Liberty National can tell stories like that? I’m not going to hazard an answer to that question. I’m sure that some can. The more the better.It’s a three-hour drive to Barrackville so I got to the plant at 5 am. John and the crew were happy to see me. There were well along with the work and were removing the blockage in the jig. Daylight came and at 7:45 AM “Rube” Hall came down to the plant to learn the progress. Rube was the Division Superintendent, an old-timer, and very direct spoken. His eyes popped when he saw me.

He asked DeBolt when I came. DeBolt told him. Rube said pretty loud ‘”Jesus Christ” this is the first time anyone in the home office ever thought enough of us to come down and try to help us.’ He was pleased, everyone was happy and Rube took me to his club for lunch. I don’t know what he reported to Johnstown, probably what he told me. The home office didn’t tell me.

But that story is not simply about getting up in the middle of the night and getting the job done. Unless you are born to wealth, as some people are, you don’t get to where you can fork out a quarter of a million dollars to join a club unless you’ve put in many all-nighters.

This is about coming to the aid of men who work with their hands under dangerous circumstances. This is about valuing their skills, well-being, and their lives.

Farmers understand this. Managers who have come up from the factory floor understand it. As do military officers who have combat experience.

Whatever their experience, I fear that the executives who brought about the most recent financial collapse, and then made money hand over fist in the bailout, they don’t understand it. Those are the men and women I fear.

If I had to guess about the membership of Liberty National, I’d guess it’s some of each. That, I am afraid, is not good enough. Not for a world where just over a year ago a hurricane blew through New York Harbor and flooded much of Jersey City, and perhaps the low lying areas of Liberty National as well. Those who can afford to join the club can also afford to live above the water. Those who take care of the grounds before 9AM cannot.

What responsibility to the members of Liberty National recognize toward the workers who maintain the grounds?