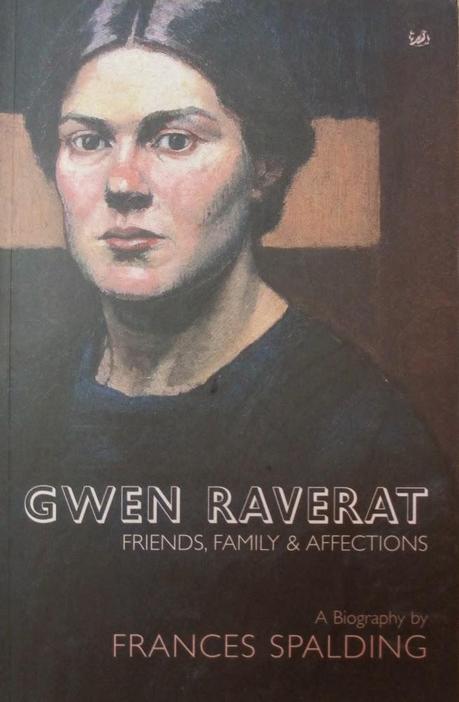

Frances Spalding, Gwen Ravert: Friends, Family & AffectionsCover design incorporating an oil self-portrait, c.1910-11

Frances Spalding, Gwen Ravert: Friends, Family & AffectionsCover design incorporating an oil self-portrait, c.1910-11Gwen Raverat was born in Cambridge in 1885. Her eccentric family were part of the intellectual elite of Cambridge. Charles Darwin was her grandfather, and late in life she wrote a brilliant childhood memoir, Period Piece, which brings the family dramas of the Darwins to life. She would be an interesting person simply for her Darwin heritage, her close involvement in the Cambridge Neo-Pagans led by Rupert Brooke, and her tangential but intimate entwinement with the Bloomsbury Group, if she herself had never produced any original art. But she did, and it is art of such quality that Joanna Selborne in the monograph and catalog raisonné Gwen Raverat: wood engraver describes her as "a major artist in a minor field".

Nightmare, or Cauchemar, or FlightWoodcut, 1909

Nightmare, or Cauchemar, or FlightWoodcut, 1909Gwen Raverat's work developed very quickly from her first woodcuts made while she was a student at the Slade in 1909, cut with a knife into softwood, along the grain. Even these are full of vitality, and one of the best is Nightmare, with its striking sense of existential angst and its strongly Expressionist aesthetic.

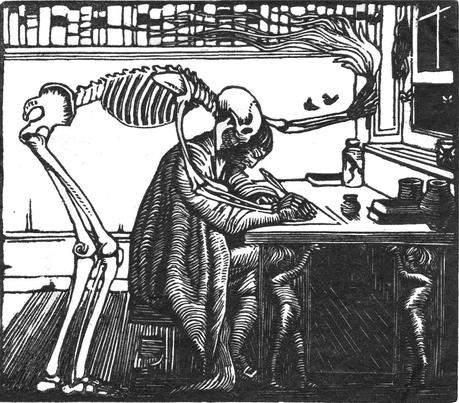

Sir Thomas Browne, state 1Wood engraving, 1910

Sir Thomas Browne, state 1Wood engraving, 1910Within a year Gwen had moved from the woodcut to the wood engraving, made on the end grain of a boxwood block - the technique pioneered by her childhood hero, Thomas Bewick. She remained true to Bewick's small-scale perfection throughout her career, and she also shared his sly sense of humor. The frontispiece she designed for Geoffrey Keynes's Bibliography of Sir Thomas Browne in 1910 is a brilliant piece of fun, with Death guiding the hand and mind of the author of Urn Burial. This impression is the first state of the engraving, before the artist filled in the blank background behind the figure of death with wood panelling, and altered the anachronistic sash window. I prefer the stark authority of this first state to the slightly cluttered feel of the second, finished state.

The Dead ChristWoodcut, 1913

The Dead ChristWoodcut, 1913 The NativityWood engraving, 1916

The NativityWood engraving, 1916As a Darwin, Gwen was raised a freethinker, but between 1912 and 1914 she went through an intensely religious phase. She and Jacques were friends and fellow-students of Stanley Spencer, and also friends with Eric Gill. Jacques dreamed of creating a temple to be decorated by the four of them, a project that never happened, though it came to a kind of fruition in Spencer's chapel at Burghclere. The Raverats and Gill also planned to publish an illustrated Gospels, a plan which fell apart over Gill's insistence on using the Catholic Bible. However the engraving The Dead Christ, engraved by Gwen after a drawing by Jacques, gives a flavor of what such a book would have been like. The resemblance to Eric Gill's work of the period is quite striking. Gwen's tender Nativity of three years later is less graphic and more intimate; the luminous sense of the play of light in the stable gives an indication of the impressionistic course that Gwen Raverat's art would take in the following years.

The Sleeping Beauty (La Belle au bois dormant)Wood engraving, 1916

The Sleeping Beauty (La Belle au bois dormant)Wood engraving, 1916The Sleeping Beauty, from the same year, is one of Gwen Raverat's most attractive images; although the print was editioned in black-and-white, Gwen hand-coloured at least one copy, which can be seen on the website of the Raverat Archive here. All of the pieces illustrated in this post come from the Raverat Archive, by permission of the artist's grandson William Pryor, the author of the fascinating Virginia Woolf & the Raverats.

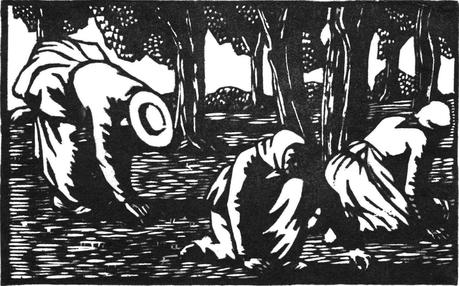

Olive PickersWood engraving, 1922

Olive PickersWood engraving, 1922 Street by Moonlight, Vence, IWood engraving, 1922

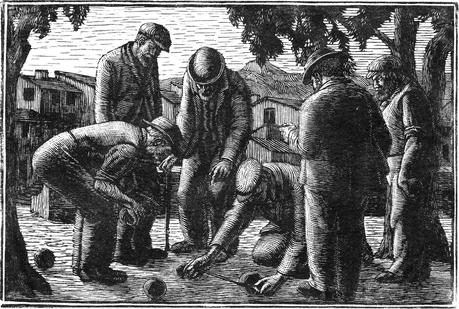

Street by Moonlight, Vence, IWood engraving, 1922 Jeu de Boules, Vence, II

Jeu de Boules, Vence, IIAs I mentioned earlier, it is Gwen's Provençal engravings that speak most strongly to me, and all the rest of the images here come from that vivid period in Vence, where Gwen nursed the dying Jacques while also nourishing her own art. The wood engravings Gwen made in Vence are among her loveliest; unfortunately the Provence climate played havoc with the woodblocks, so these exquisite works can never again be printed direct from the block.

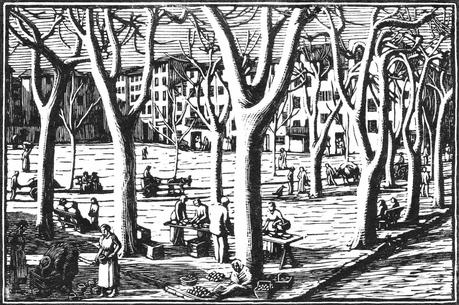

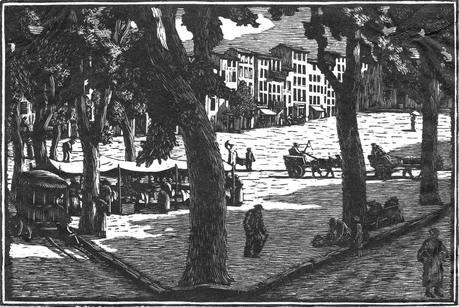

La Place en HiverWood engraving, 1923

La Place en HiverWood engraving, 1923 La Place en ÉtéWood engraving, 1923

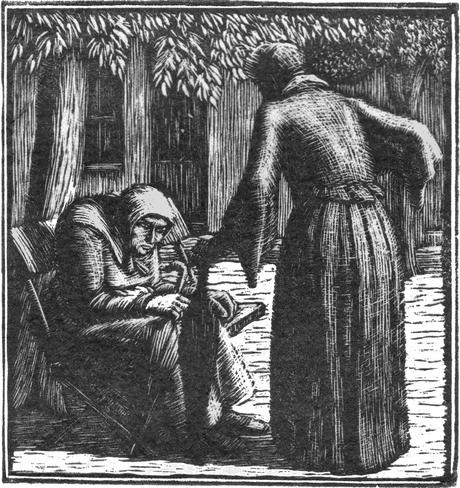

La Place en ÉtéWood engraving, 1923 Old Women, state 1Wood engraving, 1924

Old Women, state 1Wood engraving, 1924 Gwen Raverat's long and influential career as a wood engraver was cut short by WWII. In her British Wood-Engraved Book Illustration 1904-1940, Joanna Selborne writes of Gwen Raverat, "Apart from Lucien Pissarro, she was virtually the only practitioner in the early days of the revival to apply the lessons of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism and to retain an interest in light effects throughout her work."

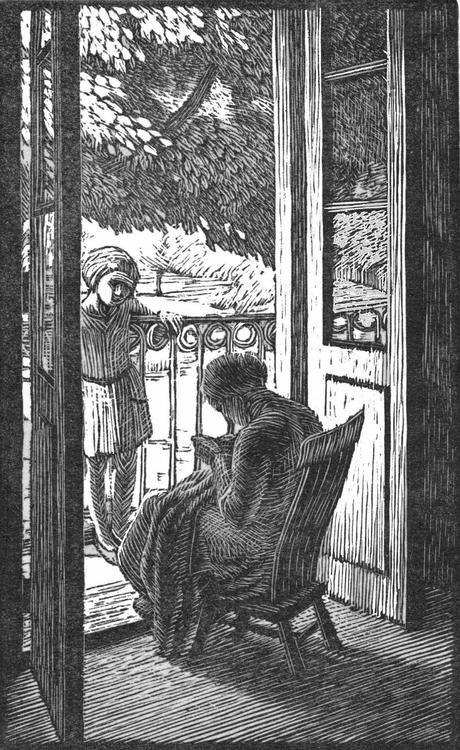

The Balcony, state 2Wood engraving, 1926

The Balcony, state 2Wood engraving, 1926In addition to the books above, I strongly recommend the biography by Frances Spalding, Gwen Raverat, a really compelling read.