Deep-sea sharks include some of the longest-lived vertebrates known. The record holder is the Greenland shark, with a recently estimated maximum age of nearly 400 years. Their slow life cycle makes them vulnerable to fisheries.

Humans rarely live longer than 100 years. But many other animals and plants can live for several centuries or even millennia, particularly in the ocean.

In the Arctic, there are whales that have survived since the time of Napoleon’s Empire; in the Atlantic, there are molluscs that were contemporary with Christopher Columbus’ voyages; and in Antarctica, there are sponges born before the Holocene when humans were still an insignificant species of hunter-gatherers (see video on lifespan variation in wildlife).

Long-lived species grow slowly and reproduce at later ages (1, 2). As a result, these animals require a long time to form abundant populations and to recover from fishing-related mortality.

Among cartilaginous fish (chimaeras, rays, sharks, and skates), the risk of extinction due to overfishing is twice as high for deep-sea species compared to coastal species, because the former have longer and slower life cycles (3).

Of course, to assess the relationship between extinction risk and species longevity, it is first necessary to measure lifespan, which presents a methodological challenge in deep-sea sharks (4).

Dating eyes

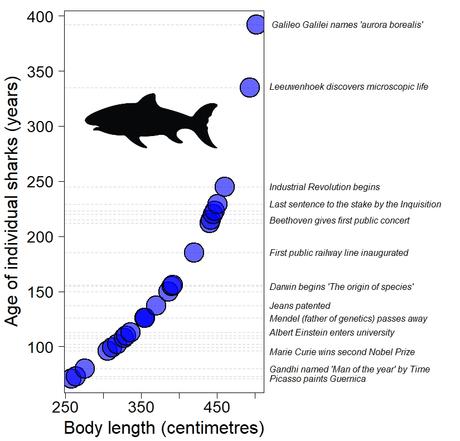

In a study that bridges biology, chemistry and geochronology, Danish researcher Julius Nielsen and his colleagues estimated the longevity of the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) by analysing 25 females accidentally caught by the country’s fishing fleet between 2010 and 2013 (5) (study featured here and here).

These sharks move from the ocean surface down to depths of around 2000 m (6, 7) (see here for submarine footage along with life-history notes of the species). What’s particularly interesting is that the proteins forming their eye lenses are synthesised during the embryonic stage, while the offspring are still inside their mothers. This means that the chemical composition of an eye lens reflects the mother’s diet and can be used to estimate the newborn’s birthdate.

Nielsen measured the concentration of radiocarbon to determine the age of the sharks’ eyes (5) (see video on estimating the age of sharks).

Radiocarbon, or carbon 14, is present in small, constant amounts throughout an organism’s life (including ours), but after death, its quantity decreases by half every ~ 5700 years (8, 9). By knowing this decay rate, the amount of radiocarbon in inert, organic materials — such as proteins in a fossilised mammoth bone or a shark’s eye lens — can indicate age (see video on radiocarbon dating and my previous blogs here and here).

Using radiocarbon dating, Nielsen found that the studied females were born between 71 and 392 years ago, reaching sexual maturity only after living for at least 150 years. This makes the Greenland shark the longest-living vertebrate known to date, surpassing the bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus) and the Floreana giant tortoise (Chelonoidis niger) from the Galápagos Islands by more than a century.

Spatial but also vertical protection

With the global decline of coastal fisheries (highlighted in documentaries Seaspiracy and The End of the Line), deep-sea ecosystems have become a new target for exploitation, both for fisheries, which are seen as a partial solution to food insecurity for a growing population of 8+ billion people (10), and for mining (see documentaries here and here).

Cartilaginous fish are clear examples of overfishing in the world’s seas and oceans (11) (watch Sharkwater and its sequel Sharkwater Extinction). One-third of threatened deep-sea shark species are already part of industrial fisheries, with half of them classified as endangered. They are exploited not only for their meat and fins, but also for the oil extracted from their livers (12).

However, the longevity and low reproductive rate of deep-sea sharks make them a finite resource — akin to mining coal (13). Fishing fleets can deplete a population that takes centuries to recover before moving on to another, much like mining companies that traverse mountains and countries in search of new coal reserves after exhausting previous ones.

On land, the extent of natural protected areas is measured by horizontal space across the landscape. In the ocean, however, effective fishery management requires additional vertical regulation — for example, setting limits on the maximum depth at which fishing is allowed (12).

This challenge is further complicated by the fact that deep-sea waters often lie in international zones, beyond national jurisdictions (14). From a scientific perspective, we must understand the life cycles of these remarkable species to inform governments about which ones can be fished and how to do so sustainably (15).

Let’s always keep in mind that the ocean is the heart of the Earth, and its health reflects the overall well-being of all living creatures.

References

- Metcalfe NB, Monaghan, P 2003. Growth versus lifespan: perspectives from evolutionary ecology. Experimental Gerontology 38: 935-940

- de Magalhães JP, Costa, J., Church, GM 2007. An analysis of the relationship between metabolism, developmental schedules, and longevity using phylogenetic independent contrasts. The Journals of Gerontology A 62: 149-160

- García VB, Lucifora, LO, Myers, RA 2008. The importance of habitat and life history to extinction risk in sharks, skates, rays and chimaeras. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 275: 83-89

- Zhang Y et al. 2024. Methodology advances in vertebrate age estimation. Animals 14: 343

- Nielsen J et al. 2016. Eye lens radiocarbon reveals centuries of longevity in the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus). Science 353: 702-704

- Nielsen J et al. 2020. Assessing the reproductive biology of the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus). PLoS One 15: e0238986

- Orlov AM, Rusyaev, SM, Orlova, SY 2022. in Imperiled: The Encyclopedia of Conservation, DA DellaSala & MI Goldstein, Eds. (Elsevier), pp. 794-800

- Herrando-Pérez S 2021. Bone need not remain an elephant in the room for radiocarbon dating. Royal Society Open Science 8: 201351

- Hajdas I et al. 2021. Radiocarbon dating. Nature Reviews Methods Primers 1: 62

- Gatto A et al. 2023. Deep-sea fisheries as resilient bioeconomic systems for food and nutrition security and sustainable development. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 197: 106907

- Dulvy NK et al. 2021. Overfishing drives over one-third of all sharks and rays toward a global extinction crisis. Current Biology 31: 4773-4787

- Finucci B et al. 2024. Fishing for oil and meat drives irreversible defaunation of deepwater sharks and rays. Science 383: 1135-1141

- Norse EA et al. 2012. Sustainability of deep-sea fisheries. Marine Policy 36: 307-320

- Oanta GA 2018. International organizations and deep-sea fisheries: current status and future prospects. Marine Policy 87: 51-59

- Priede IG 2017. Deep-Sea Fishes: Biology, Diversity, Ecology and Fisheries (Cambridge University Press), pp. 504

- Walter RP et al. 2017. Origins of the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus): impacts of ice-olation and introgression. Ecology and Evolution 7: 8113-8125

- Grant SM, Sullivan, R, Hedges, KJ 2018. Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) feeding behavior on static fishing gear, effect of SMART (Selective Magnetic and Repellent-Treated) hook deterrent technology, and factors influencing entanglement in bottom longlines. PeerJ 6: e4751

- Lydersen C, Fisk, AT, Kovacs, KM 2016. A review of Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) studies in the Kongsfjorden area, Svalbard Norway. Polar Biology 39: 2169-2178

- Fields RD 2007. The shark’s electric sense. Scientific American 297: 74-81