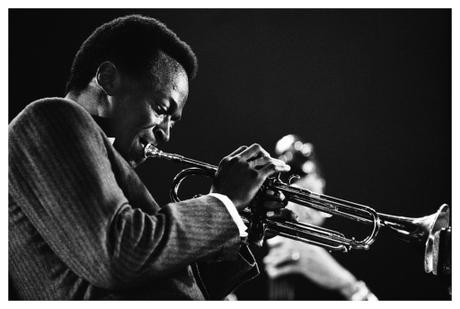

Miles Davis (1926-1991), playing in France, ca. 1967

Miles Davis (1926-1991), playing in France, ca. 1967It was that voice. Harsh, gruff, low, and gravely, like crumbled up shreds of sandpaper. And that sullen personality. Surly, brooding, a chip strategically placed on his shoulder. That’s what got my attention.

The first time I heard the Miles Davis sound was almost 30 years ago. The same co-worker, Mike, who had introduced me to smooth jazz and the Brazilian artists who played it also sold me on Miles.

“Got a great album for you, Joe” Mike claimed. “You’re gonna like this.”

“Like what?” I asked.

“Miles,” he answered.

“Miles? You mean Miles Davis? The jazz trumpeter?

“The same.”

“Didn’t he pass away the other day?”

“Yeah. I’m gonna record him for you. Give it to you tomorrow.”

And he did. Mike gave me a cassette version, which I still own, of Miles’ late 1980s album You’re Under Arrest. I heard it later that same evening. Smooth, rich, the musical equivalent of chocolate ice cream. Miles in mellow form, both haunting and elegiac at the same time, on trumpet and flugelhorn. I loved it, couldn’t stop listening to it. Especially his take on Michael Jackson’s “Human Nature” and Cyndi Lauper’s “Time After Time.”

The album started off with street sounds. Manhattan street sounds. Noise, crosstalk. The crosstalk turned into indecipherable chatter, rising in volume and pitch until it ended with shouting. Chaos, traffic. Police sirens, pedestrians, confrontation. The sounds of summer in New York, the city that never slumbers. Yeah…

That was Miles.

Miles and Beyond

I knew very little about the jazzman named Miles. Miles was just a name to me, like so many others. His full name was Miles Dewey Davis III, christened after his father, a ranch owner and successful dentist. Miles came from East St. Louis, Illinois, of solid middle class stock. Even then, pre-war, it was as tough a place as any for a shy kid like Miles to be raised in. I should know, having grown up in the South Bronx.

Back then, I knew next to nothing about Miles’ music. I knew he played jazz. Traditional jazz. Jazz with a capital “J.” He also played bop. Cool jazz. From cool jazz came bossa nova, so claimed my friend Mike. And from bossa nova, back to jazz again — or smooth jazz, as it was now called. Terrific stuff.

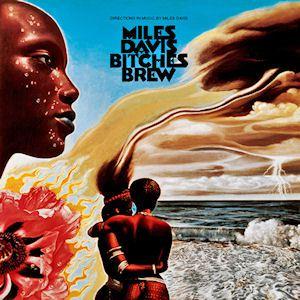

His albums were classics. Bitches Brew served up innovative jazz fusion mixed with rock. It featured Chick Correa, John McLaughlin, Joe Zawinul, Wayne Shorter, Jack DeJohnette, who went on to make names for themselves. And there were more names, all of them associated with Miles in one form or another. Jazz people, key figures in his life and art. Billy Eckstine, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, John Coltrane, John Lewis, Gerry Mulligan, Bill Evans, Gil Evans. Giants who once walked this Earth.

There were other music styles as well. Funk, R&B, disco, pop. There were combos, big bands, quartets, octets, nonets, and such. And there were gigs, hundreds of them. Record dates, too, club dates, and all-night jam sessions. All the things that jazzmen were known for. And, of course, the drugs. Lots of drugs. Drugs to stay awake, drugs to go to sleep. Drugs to keep on moving, drugs to slow the jazzman down.

Jam all night, jam all day, play hard, play rough, play again through the night. Get some sleep. Sleep? What’s that? And there were women, lots and lots of women. Black, tan, white, brown. It didn’t matter. Frances Taylor, Betty Mabry (later Davis), Cicely Tyson, so many others. The names came, and they went.

When Miles traveled to Paris, he met and fell hard for Juliette Greco, a dark-haired beauty, French singer-actress. Their affair was unlike any other in the City of Light. Miles was treated with respect while he was there. Almost like a king. More like a prince. A dark prince. Not like in America, where he was beaten up and bloodied.

He married and divorced often, as did the poet, musician, and performer Vinicius de Moraes in Brazil. Miles put his women on a pedestal, or on his album covers which were the next best thing. The albums became noteworthy because of them: Some Day My Prince Will Come, E.S.P., Sorcerer, Nefertiti, Filles de Kilimanjaro, and lastly Bitches Brew. The beauty of black women, for all to see, graceful and sleek, up front and personal — in your face and in your home, lovely to look at as well as to listen to. The music, that is.

He had a violent streak, what we call “anger management” issues. He took them out on the women. Battered and bruised, what he took from brutish treatment he doled out in like form.

Yeah, that was Miles.

Miles Mannered

Miles was neat and trim, strong and hearty, cut from the finest cloth. His frame was angular and small; eyes large, white background and bulbous, black fire in his pupils. The skin was black as well, dark and glistening, gleaming brilliantly in the light as sweat poured down over his finely sculpted features.

In the early days Miles kept his hair short, neatly cropped and trimmed and even all around. Later, he sported a Black Power “Fro,” de rigueur for African-Americans of the late 1960s and 70s, and later still it came down in tresses to his shoulders, then not so broad as in his youth. He refused to wear a beard or a goatee. That was for sissies! Dizzy had a little fuzz between his lip and chin, and was fond of his beret. Miles preferred the lean and hungry look. No sense covering up that face. He was stylish to a fault, flaunting his taste for the finer things in life.

He was a snazzy dresser, too, with shirts that were always starched and neatly pressed, suits immaculately tailored. Slacks long and trim, covering his spindly legs. Shoes polished to a high buff shine. When psychedelia became all the rage, Miles chose carefully coordinated, colorfully flowing wide-sleeved vestments made of the purest silk. Radical chic, I would think.

That was Miles.

Then there was the music: spare, lean, no bullshit; all killer, no filler. Ballads and mid-tempo items were his specialty. Cut to the chase, that was his maxim. The arch romantic in sound. Unlike his contemporaries, Miles lacked virtuoso command of his instrument. That’s all right. We loved him anyway. Many didn’t. More fools them!

Herbie Hancock told a story once about an early recording session with the great man himself. Fumbling for guidance, Herbie sat down at an electronic piano, a Fender-Rhodes, something he had never seen before.

Herbie turned to Miles and queried: “Miles, what do you want me to play?”

Miles, hoarse, pointed at the instrument and growled back his reply. “Play that, motherfucker.”

Just another one of his quirks. His language: salty, mean, cut to the bone, as sharp as a serpent’s tooth, so said Shakespeare. Like his music, it went to the meat of the matter. It signaled to all comers, “Don’t fuck with me, man.” It was all just a cover, Miles’ way of overcoming his ever-present shyness, add to it the loneliness, the pain, the despair all jazzmen carry with them.

He called people an infinite variety of the “F” bomb. On anyone else’s lips, it might have sounded gross or revolting. Coming from Miles, it was poetry. How many ways could he say “fuck,” “shit,” or “motherfucker,” and still make them sound fresh and true, joyous and mirthful, sad and tragic? To him, they were more than verbs and epithets, more than adjectives and nouns, and every permutation in between. Like bop and modality, they were as much a part of his music and makeup as everything else.

If he liked you, he would call you a “motherfucker.” No offense intended, none taken. If he hated you, or was angered by you, he’d say the same thing: “That guy was a motherfucker.” The words may have been similar, but the context was something else entirely. You’d have to be smart enough to discern the difference. He demanded it. No apologies necessary, none given.

That, too, was Miles.

I Can See for Miles

Then, there were the records. Lots and lots of records. Thank God for that! We have him preserved for all time: first on vinyl, then in CD format; an Egyptian treasure trove of solid gold. A bountiful harvest, one might add. The early hits: Birth of the Cool, Miles Ahead, Kind of Blue, Sketches of Spain, Porgy and Bess, Quiet Nights.

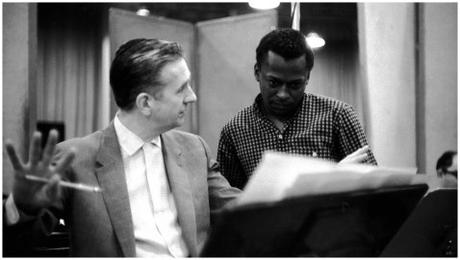

Gil Evans, Canadian by birth, arranged them. Miles Davis played his heart out for him on them. Black man, white man, making music together as musician and friend, close friends to be exact. Miles loved Gil, and Gil loved him back. “Gil and I hit it off right away,” Miles recalled in his autobiography. “I could relate to his musical ideas and he could relate to mine. With Gil, the question of race never entered; it was always about music … He was a beautiful person who just loved to be around musicians.”

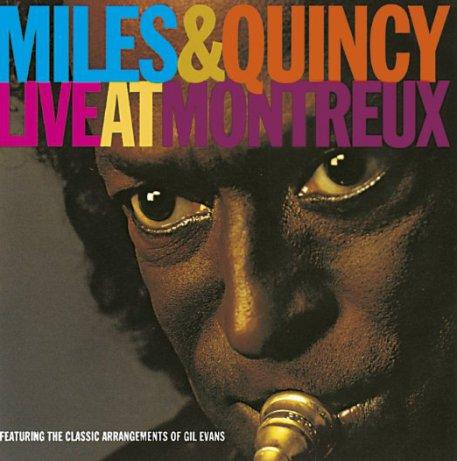

Then came the later fusion stuff, the jazz-pop albums, and the Quincy Jones-produced pieces of art. And, of course, the final concert, Miles & Quincy Live at Montreux — a latter-day classic. This was Miles reliving the past — the glory years, if you will — rediscovering a lost love for the dearly departed, his pal Gil Evans, and his groundbreaking arrangements. The artist came alive once more, through his music and his artistry.

The last years were difficult ones. He looked weather beaten. Illness of body and mind had taken their toll; the formerly ironclad frame had turned thin and frail from too much of, well, pretty much everything. The face was spared but the rest ached and screamed. Sex, drugs, hard living, and hard knocks, the harshness of the jazzman’s life. Then death.

Finally, the accolades. Ellington was Duke, Basie was Count, but Miles was Prince. The Dark Prince — always was, always would be. First in line to the jazzman’s crown. Writer, jazz buff, entrepreneur Bret Primack dubbed him the Picasso of Jazz. Some truth in that. But that’s not quite right, is it? Sure, Miles changed with the times, transforming himself, reinventing himself every few years or so. His clothes and hair changed along with him. But his manners stayed the same. Picasso lived longer, well into his 90s. Miles died relatively young. He was 65, a lot older than most jazzmen of his day. But a Picasso? Well, maybe….

He was more of a Paganini, the greatest concert violinist of his day. Paganini made a pact with the Devil, to play the Devil’s music as only the Devil could play it. Miles, too, must’ve bargained with Old Beelzebub, or some higher authority. I can hear him now: “Come on, man, gimme one more day. One more shot at immortality. Lemme play my old stuff again. Huh? Sheeyut! Whatta ya say, Bub?”

Heh! That Devil never knew what hit him. If anything, Miles got the best of that deal. He got one more gig to play, and several thereafter. He lived and he loved, and he played and played and played, almost to the last.

As Miles Davis approached the Pearly Gates, he saw that St. Peter, the gatekeeper, wasn’t around. Carrying his trumpet under his arm, Miles walked leisurely up to the Gates, to the fellow who was there and asked, “Hey, man, where’s St. Peter? And who the hell are you?”

The figure looked up and responded. “I’m the Archangel Gabriel. Peter sent me ahead to greet you.”

Miles answered. “Oh, he did?” Fidgeting to hide his restlessness, Miles inquired, “So, Gabriel, what do you want me to play?”

Pointing to Miles’ trumpet, Gabriel smiled wickedly and replied, “Play that, motherfucker!”

THAT’S Miles Davis.

Copyright © 2016 by Josmar F. Lopes