It feels like an age since I’ve written about any books. This must be partly because the books I’ve been reading lately have often left me uncertain how I feel about them. I’m not sure whether it was because of the writing course, which encouraged us to unpack pieces of writing (I’m not exactly unused to that) or whether it’s just been the nature of the past couple of months with their run of irritations that have put me in a funny place in relation to my books. It’s one of the great paradoxical truths of existence that the more you long for things to be perfect, the less likely it is that they will be so.

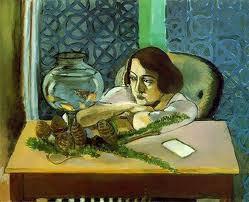

Nothing ruins the experience of a book more surely than having too high expectations for it, and I wonder whether that was at the root of my troubles with Patricia Hampl’s Blue Arabesque; A Search for the Sublime. In theory this ticked all my boxes. I’d read one of Hampl’s essays on the writing course and been very impressed by it. This book was exactly the sort of hybrid creative non-fiction that I am most interested in, a journey across time and space that begins with the sighting of a Matisse painting in the Art Institute of Chicago. A young woman at the time, Hampl is on her way to lunch with a friend when she is stopped dead in her tracks by Matisse’s picture of a woman contemplating goldfish in a bowl. Something about the woman’s attitude, the timelessness of her gaze, the relaxation of her posture, appeals strongly to Hampl but resists articulation. Armed with the belief that the woman in the painting represents a way of seeing that is intrinsic to art and highly valuable to life, Hampl enters into a length meditation that encompasses the lives of artists she loves, as well as trips to the locations where they were inspired, and her thoughts on the work they produced.

Nothing ruins the experience of a book more surely than having too high expectations for it, and I wonder whether that was at the root of my troubles with Patricia Hampl’s Blue Arabesque; A Search for the Sublime. In theory this ticked all my boxes. I’d read one of Hampl’s essays on the writing course and been very impressed by it. This book was exactly the sort of hybrid creative non-fiction that I am most interested in, a journey across time and space that begins with the sighting of a Matisse painting in the Art Institute of Chicago. A young woman at the time, Hampl is on her way to lunch with a friend when she is stopped dead in her tracks by Matisse’s picture of a woman contemplating goldfish in a bowl. Something about the woman’s attitude, the timelessness of her gaze, the relaxation of her posture, appeals strongly to Hampl but resists articulation. Armed with the belief that the woman in the painting represents a way of seeing that is intrinsic to art and highly valuable to life, Hampl enters into a length meditation that encompasses the lives of artists she loves, as well as trips to the locations where they were inspired, and her thoughts on the work they produced.

What’s not to like? The artists considered include Matisse and Delacroix, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Katherine Mansfield – a small constellation of stars in Hampl’s inner universe. And the travel writing, moving from Minneapolis where Hampl lives, to the Côte D’Azur and North Africa provides suitably glossy and exotic locations. What appears to be the main thrust of the series of interlinked essays – that the speed of the modern world makes us miss the sort of experience that end up being most valuable to us – is one I wholeheartedly endorse. And in all honesty there is much to love in this book, so many exquisite sentences, beautiful, vivid imagery, some nice points made, and at all times Hampl’s intelligence shines through.

But I just could not stay awake while reading it.

There is a fundamental problem with this kind of hybrid writing that skips between memoir, biography and criticism, and that’s the difficulty the reader is bound to experience trying to hang onto the point. I find that, like a complex dream, all those weird shifts between heterogeneous scenes erase what came before, and I can lose whole chunks of narrative, forget them as if I’d never read them. I finished this book only a couple of weeks ago and have retained practically nothing from it. No, in all fairness, I recall the travel writing, which was excellent. And I felt that in those scenes something was happening, something I could really engage with. Hampl’s art criticism, whilst always intelligent, tended to sink into the swamp of its own thought, witness this small excerpt where she is talking about an autobiographical film:

I was listening to a memoir, the genre that inhabits a fascinatingly indeterminate narrative space between fiction and documentary. As it refines its point of view, lavishing itself on the curious habits of personal consciousness, memoir achieves a rare detachment even as it enters more deeply into the revelation of individual consciousness. Its greatest intimacy (the display of perception) paradoxically reveals its essential impersonality. It wishes to see the world, not itself. Hill’s real subject, like Matisse’s was individual perception: not simply what was seen, but how seeing was experienced.’

A few paragraphs like this strung together and I was out like a light. Which goes to show that, like everything else, critical writing needs to keep the concrete in sight at all times. The more grounded the writing, the more it is about something real, the better the chance of hanging onto the reader’s attention. But this book frustrated me, as I felt it had a lot of interesting things to say, and I really did wish I could stay conscious long enough to hear them.

Altogether more grounded was Cathleen Schine’s The Three Weissmanns of Westport. In my twenties I’d enjoyed her first novels, The Love Letter and Rameau’s Niece and recalled them as being sort of literary rom-coms. Not a lot has changed in the intervening decades – the Weissmanns tale being loosely based on Austen’s Sense and Sensibility. I forgot this detail until halfway through the novel, when I thought to myself, ‘goodness me, these sisters are exactly like Eleanor and Marianne Blackwood!’ and recalled that this was, in fact, the point. And then I was aware enough of these literary ghosts to watch the novel diverge from Austen’s plotting and play a few neat tricks with its model. Just in case you were wondering how that particular borrowing worked out.

Altogether more grounded was Cathleen Schine’s The Three Weissmanns of Westport. In my twenties I’d enjoyed her first novels, The Love Letter and Rameau’s Niece and recalled them as being sort of literary rom-coms. Not a lot has changed in the intervening decades – the Weissmanns tale being loosely based on Austen’s Sense and Sensibility. I forgot this detail until halfway through the novel, when I thought to myself, ‘goodness me, these sisters are exactly like Eleanor and Marianne Blackwood!’ and recalled that this was, in fact, the point. And then I was aware enough of these literary ghosts to watch the novel diverge from Austen’s plotting and play a few neat tricks with its model. Just in case you were wondering how that particular borrowing worked out.

At the tender age of 75, Betty Weissmann finds herself being divorced by husband, Joe, on grounds of irreconcilable differences. ‘Irreconcilable differences? she said. Of course there are irreconcilable differences. What has that to do with divorce?’ Of course, there is another woman, Joe’s secretary, Felicity, and Felicity manages to talk Joe out of leaving the New York appartment to his estranged wife on the grounds that it is much more generous to take the burden of worry about taxes from Betty’s shoulders. So Betty finds herself exiled and downsized to a holiday cottage owned by wealthy, family-loving cousin, Lou in Westport, Connecticut. Partly to support their mother, mostly because of financial crises of their own, Betty’s daughters Annie and Miranda move out to live with her.

Annie is the sensible, one, a divorced librarian with two grown boys, who is impotently aware of her mother and sister spending far more money than they possess. Miranda is the flighty one, a literary agent recently humiliated and put out of business by revelations that the misery memoirs she traded in were more fiction than fact. The family hasn’t been in Westport long when Miranda starts a relationship with an out of work actor, Kit, and his enchanting little son, Henry. Meanwhile, Annie pines silently for Felicity’s brother, Frederick, a writer with whom she has been briefly entangled, but who is now persona non grata for obvious reasons. Best of all, nothing works out the way you might think it would. This was charming and funny and intelligently written enough that it was like hot chocolate with marshmallows and whipped cream and no guilt. If such a thing as a poignant soufflé existed, I could liken this book to one. Don’t come to it expecting Tolstoy, but the quality of the writing and the insights about love and life lift it above the level of your average comfort read.