Dutch self portrait (c) Samantha Groenestyn (oil on linen)

Early Rembrandt: his colours are bold and gleaming, his compositions elaborate and ambitious; the drawing is wobbly in places. But Rembrandt is unmistakably there right from the beginning. His early Historical Scene reminds me of the clumsy vigour of the youthful Velazquez who, in just a few short years, elevated his painting dramatically, adhering to his same vision but finding more and more assured means of expression. Delacroix (2010: 141) exclaims of Rubens: ‘It is very evident that Rubens was no imitator; he was always Rubens.’ One feels seized by the same conviction when one stands before an early Rembrandt, and this is reassuring. Finish and fluency come with time; originality of conviction and sensibility shine through in spite of underdeveloped abilities.

Detail of Rembrandt, Historical scene

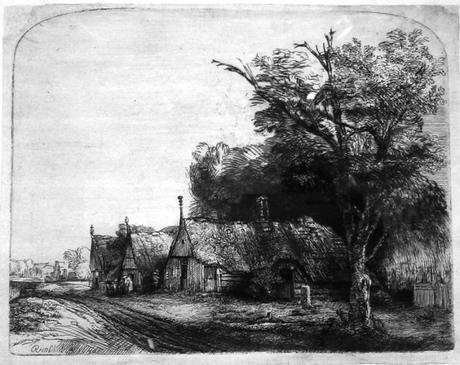

The Rembrandthuis is a veritable cavern of treasures, augmented by the practical demonstrations of printing etchings and mixing up paints from pigments. Huddled in Rembrandt’s tight and dim etching studio, privy to etching, drypoint and engraving techniques, peering into pots of ink made of burnt rabbit bones and linseed oil, watching the hasty print come out clouded with too much ink on the clear surface, one emerges with an entirely different understanding of what Rembrandt produced. Encountering prints made by his own hand, and able to compare them with the efforts of others to recreate them from the same plates, or to make copies of them, one is struck by the artistry of the entire process and of the masterful hand and inventive mind behind them.

Rembrandt’s atmospheric prints make use of a full spectrum of techniques, he pushes every method for what it can give him, overlapping and merging and setting them off against each other to maximum effect. Drypoint curves with their fuzzed burrs render hazy leaves blowing in the trees, but crisp, sharp, engraved lines lightly caress figures in blazing light in the foreground. The darks are an absorbing mixture of furious hatching and the controlled rubbing of ink; they transition thickly into light passages, and one appreciates that this transition is supplied deliberately and carefully, it does not take care of itself or lazily blend two unrelated areas.

Rembrandt

That thick hatching is never harried or negligent; it alters course because the image takes it there. Rembrandt is unafraid to search around the surface of the object as if actually feeling his way around it, little clumps of hatches rolling this way and then that way, breaking into each other like rippling waves in a canal. His inventiveness with mark-making is astonishing, lively and ever responsive to the subject.

Rembrandt, Militia Company of District II Under the Command of Captain Frans Banninck Cocq, known as the Night Watch, 1642

Returning to the Rijksmuseum to see his paintings, after emerging from the intricate world of his etchings, his compositional prowess is instantly striking. It migrates directly from his small and tightly-spun etchings to the grand format, bringing its seething dark patches and soulful transitions into the light and its expert contrasts that make the light flash where it really needs to. We are all painting with the same ground up bits of dirt in linseed oil. But Rembrandt knows how to find an impressive range within the mix, how to play tones and textures off against one another for specific effects of light, how to use lightness of touch to convey brilliance, how to deepen space with quickly engulfing shadows. The Night Watch dazzles less for its individual perfections but rather for its pictorial unity. The pictures that flank it, decked with smooth drawing and inventive rendering, ring with even-handed clarity. Each face in them is well-depicted, each pose carefully arranged and interlocking with the next, each figure grouped with others, yet shown in its individuality. Yet in these pictures, composition is conceived much more as a linear arrangement of given subjects. Rembrandt sacrifices much–he gives us stumpy legs and obscured faces–but he has puzzled over how to present us with a picture, not simply a spread of information. The vast stretch of darkness across the top reads just like his etchings–a thick darkness hangs heavily over the militia, certainly unnecessary for the reproduction of their likenesses, but indispensable for a resonant, night-swamped image.

Amsterdam

Delacroix (2010: 209) laments that ‘The majority of painters who are so scrupulous in their use of the model spend most of their time putting faithful copies into dull and ill-digested compositions. They believe that they have accomplished everything when they reproduce heads, hands and accessories in slavish imitation of nature without any relationship with one another.’ One is left in no doubt that Rembrandt digests his compositions–that his smaller works, many of them hardly more than thumbnails, give him such a sense for the whole, allow him to extract salient passages and subdue others, or weave them more subtly together, in a way that eludes more faithful painters. His compositions do feel chewed–it feels as though he is intimately acquainted with them, as though he has explored every crevice of them and considered their weight and role with respect to the whole. And seeing etchings in their first, second, sixth, seventh states, seeing the gentle alterations, and the sometimes dramatic revisions, one sees that Rembrandt considered and reconsidered, reworked his images, knew them thoroughly and beat them into the shape he wanted. This is a kind of familiarity and deliberateness that one does not meet with often.

Amsterdam

Delacroix, Eugène. 2010. The journal of Eugene Delacroix: a selection. Edited by Hubert Wellington. Translated by Lucy Norton. London; New York: Phaidon Press.