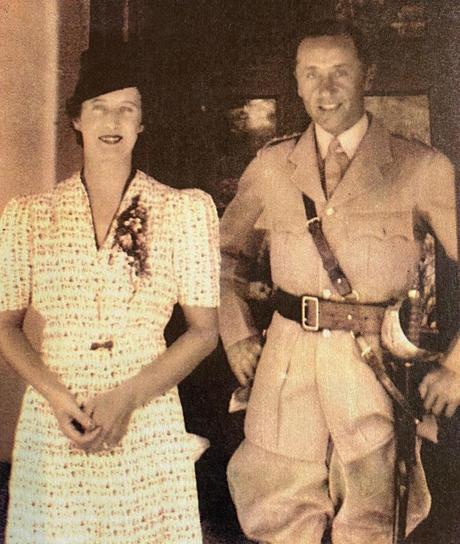

In 1947, my great-aunt Ena moved from India to start a new life in Kenya with her husband Jimmy Power, an Indian army officer. The goal - as for so many expats after the Second World War - was to build a farm, in this case near Nakuru, about 130 kilometers northwest of Nairobi in the Great Rift Valley.

They followed a well-trodden path. For Victorian Britain, control of East Africa would ideally have been left to the Sultan of Zanzibar, with Britain acting as advisor, a model that had already proven workable in Egypt. However, the competition with the other major European powers in the 1880s was such that the upper reaches of the Nile, and thus the Suez Canal and the trade routes to India, became a crucial strategic asset (just as they remain today ). A railway line was built from Mombasa to Uganda to control the Nile and from this project British East Africa - which eventually became Kenya - was born.

In 1897, Hugh Cholmondeley, third Baron Delamere, convinced the governor, Sir Charles Eliot, to consider the idea of encouraging white settlers to settle in the highlands. (Eliot was under pressure from Whitehall, as every train that traveled along the line did so with heavy casualties.) Most of these settlers came from the upper and middle classes of British society, with strong ties to large public schools and elite Guards and Cavalry regiments. They had ties to both the Colonial Office and the capital and used these to develop large areas of land. These first settlers were followed after the world wars by two more separate soldier settler schemes, one in 1920 and the second in 1946-1947, when the powers arrived.

Great Aunt Ena, who spent her days in a nursing home in Barbados, was always full of stories about life in Kenya. I vividly remember her telling me stories about the two man-eating tigers Jimmy had to shoot in India to save a village, and about their many adventures in Africa when I visited her in 2010. She also wrote a book titled Looking for change about agriculture in Kenya, and I still have a copy.

As well as describing how they turned their thousand hectares of woodland on steep terrain into a highly productive mixed farm, it offers some intriguing arguments for artificial insemination of their dairy herd, after they purchased an unreliable Jersey bull that would not 'soldier'. . Her life, and the photo album I inherited, have long prompted me to visit her former home and discover more about those who left after independence in 1963, like her, and those who stayed.

"The winds of change are blowing through this continent whether we like it or not," said Harold Macmillan in 1960 during a policy of divesting colonies in Africa. Kenya was a problem. Not only was it a settler colony, but it was also of critical strategic importance in the context of the Cold War. Britain and the US did not want an unstable Kenya, which would have given the USSR a foothold in East Africa.

As a result, the Land Settlement Scheme was introduced between 1960 and 1976 to facilitate peaceful transfer of land from the settlers to the indigenous people; it became the only plan of its kind in the entire history of the British Empire. Settlers - including Ena and Jimmy - were bought out of their farms on a 'walk in, walk out' basis, paid for by the British government.

This land was then subdivided and sold to African farmers using loans financed by the World Bank, the Commonwealth Development Corporation and the British government. However, the larger landowners who have not sold into the Settlement Scheme are still in Kenya and have converted their cattle ranches into mixed-use nature reserves. Under this model, wildlife tourism, livestock farming and grain farming will take place on the same site, all managed together.

Earlier this year, a friend who is still a Kenyan farmer of that ilk invited me to stay - and so began my journey to the site of Ena and Jimmy's farm (named Waterford, in a nod to their Irish heritage ) in the Great Rift Valley. .

Armed with an iPhone, a ten figure grid reference and Ena's book describing the ground, we set off for the highlands above Nakuru and soon managed to follow Google Maps to where Waterford Farm should be. It took us to a grand two-story colonial house. My friend, who speaks fluent Swahili, started talking to the residents. This was the house of Commander Good, who from the book was a good friend of Jimmy and Ena. "Do you know where Colonel Power's house was?" my friend asked. The lady of the house pointed through the trees: "There is the house of the Powers."

The Powers developed Waterford Farm as a going concern, eventually employing around 100 people; they built a school and a health center for their employees. Jimmy dug a lake with a shovel and some oxen, developed a dairy herd of about 500 cows and grew grains. But with the uncertainties of independence they surrendered to the government plan, then returned to South Africa, Devon and finally settled in Barbados, where Ena was headmistress of the girls' school for many years. The farm has been in local hands ever since.

Today, much of their efforts can still be seen. Their house itself is the kind of large stone bungalow you see everywhere in Kenya. Well built and expanded a bit over the years, but the veranda is exactly as in the photo I have from Ena. Standing in the same spot as them from the photo album, I could feel some of their spirit and adventure. Life was extremely hard in the beginning. They had to provide water supplies and sanitation, including a long drop toilet, and lived off the savings and friendships of other settlers and locals until the farm was viable.

The landscape is disarmingly similar to the Nadder Valley, where I live in south Wiltshire: rolling green hills dotted with woodlands. Although I should point out that the roads around Waterford Farm have fewer potholes than the roads around Tisbury. Well built by Jimmy and his workers over 80 years ago, they are still maintained by the local agricultural co-operative.

The lake and surrounding fields have changed little from Ena's time; the dairy and parlor are long gone, but much of the fencing is intact, and the fertile soil still bears the produce to feed the neighborhood and no doubt beyond.

Of course, Kenya is now a very different country from the one Ena arrived in almost 80 years ago. The shocks of independence and the post-colonial world are still felt, through occasional terrorist threats from the north and the dire poverty of Nairobi's slums. The gap between rich and poor is enormous, and corruption is still widespread among public and private institutions. Tourism - much of it on land reclaimed for wildlife in the intervening period - is now vital to the economy.

After my pilgrimage was complete, I took the opportunity to get a taste of this side of things on a four-day tour with Offbeat Safaris at Mara North Conservancy. Run by the Maasai tribe, with Jennifer in charge of activities and Joseph our guide, our stay was based at the Offbeat Mara camp.

Each day started with a cup of tea and then we set off for the first ride as the sun rose on the Mara from the east. Breakfast at 9am was taken by a river or on a hill, with lions or hippos for company, and then we were back for lunch and a siesta during the heat of the day. An evening ride was followed by sundowners, as the sun left the Mara.

As a former agricultural student, I was hugely impressed by how the Mara is now run, and by the people who should run it: the Maasai. Game once hunted by rich men with guns is now hunted by tourists with cameras; both are financially sustainable, but the latter is much more in line with modern values.

And our safaris were truly magical, every day. "You must leave the Mara as you found it and with Africa in your heart," says Jennifer, and that is what we did.

Of course, Britain must take responsibility for its colonial past. But it is also true that many of the settlers who left our shores and traveled around the world did enormous good. I am proud of what Ena and Jimmy have achieved in Kenya, and to see that Waterford Farm is still viable and feeding the local population sixty years after they left is a testament to their endurance, fortitude and determination to make things work and make it better.

Essentials

Kenya Airways (kenya-airways.com) and British Airways (ba.com) fly daily from Heathrow to Nairobi. Offbeat Safaris (offbeatsafaris.com) offers a four-day safari at Mara North Conservancy from £2,000 per person based on two people, including all meals and drinks, and two game drives per day. Return transfers from Nairobi with Safarilink (flysafarilink.com) cost approximately £150 per person.