By Jonathan Morris, Antiscribe.com

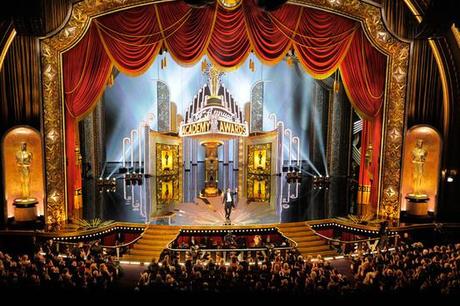

It has now been about three weeks since the 2012 Academy Awards telecast aka “the Oscars,” aired. Generally speaking, the Oscars represent one of the biggest televised events of the year, typically second only to the Super Bowl here in the United States; unlike the Super Bowl, however, the Academy Awards have not been setting new ratings records each year, instead having struggled with trying to ebb an annual ratings decline. This year saw the Oscars stem that decline, briefly, with the much-ballyhooed return of Billy Crystal to hosting duties; despite that, it still garnered lower ratings than this year’s Grammys (which were admittedly inflated by the death of Whitney Houston the day before), the demographics for the show in the key 18-49 demographic were unremarkably flat with earlier years, and the show received fairly poor reviews almost across the board. What bothered me most about this year’s Oscars, though, was just how depressing and disheartening they were about the movies themselves, and how uncertain they seemed about the very medium they were ostensibly celebrating.

Billy Crystal getting electrocuted (a spoof of "The Artist," from the Oscars' opening montage); an unintentional metaphor for the show's critical response.

While nowhere near the debacle that last year’s event was, the night was defined both by Crystal’s poor material and a tired, heavy-handed theme centered on “going to the movies.” Hopefully, emphasizing that the Academy Awards are hardly true measures of the comparative quality of particular motion pictures within a calendar year is unnecessary; what the telecast is, at its core, is an advertising tool for higher-end motion pictures, and more importantly, Hollywood itself. It’s the industry’s way of selling its image; to spotlight its biggest icons, its rising stars, its legacy, and, most importantly, the way it delivers its core product. To this aim, most years the Oscars choose to spotlight a certain aspect of film, such as a particular genre or experience. This year, the Oscars chose to spotlight, specifically, the act of “going to the movies.” The entire night was constructed on making relevant, through nostalgia, the theatrical film-viewing experience; stars, actors, directors, and so forth gave brief, talking-head blurbs about their first time going to the movies, about how much it meant to them, and about how the act of seeing movies itself remained constantly and consistently relevant. The live entertainment company Cirque du Soleil staging an extended sequence designed around going to the movies, and later glamorous usherettes came out during a commercial bumper to hand out popcorn to the audience. Even Crystal, though only half-heartedly, got in on the sentimentalism from time-to-time. There could be no conceivable doubt that this was an Oscars with its eyes firmly fixed towards the past, its entire theme devoted towards manufacturing nostalgia for its medium of choice; if last year’s Oscars wanted to acknowledge, at every turn, that it was aiming for the youth audience, this one seemed more like earnest damage control for a medium whose producers appeared afraid of seeing fade away.

As part of its nostalgic push for cinematic viewing, the Oscars hosted a live performance by Cirque du Soleil based around seeing a film in a theatrical setting.

While the Oscar telecast is always predicated on showcasing or celebrating some aspect or appreciation of movies, the producers were trying much too hard to make their point, and doing so, frankly, at the expense of their own telecast. Arguably, that sense of desperation even extended to the Oscars awarded. Now much ado has made recently about an article published in The Los Angeles Times a few days prior to the telecast that broke down, demographically, the membership of the Motion Picture Academy of Arts and Sciences, whose members vote on the Awards. The results – that they’re mostly white men in their sixties – should not have been surprising (though it should certainly be both frustrating and disappointing). Based on the article’s findings, many have laid this year’s disappointing Oscar ceremony at the feet of the Academy’s membership. Perhaps in regards to the voting, that would likely be fair. The members, though, don’t produce the show; that role belongs to the professionals, and this year, one of Hollywood’s biggest power brokers, Brian Grazer, was the main man behind the curtain. To me, the actual winners selected are typically pretty irrelevant; determined as they are, far less by what Academy members (or anyone else) truly think are the best films, than they are by those members’ extremely esoteric leanings, the campaigning abilities of studios and publicists, and basic industry politics.

An article published by the Los Angeles Times revealed that members of the Academy were predominantly old and white; and as indicative of the industry's elite, only provides further evidence of the notion that they are painfully out of touch. (Image courtesy of Salon.com)

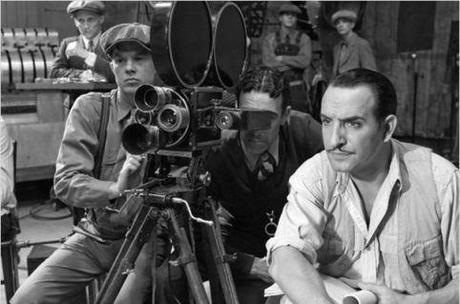

This year, though, the two films most smiled upon by Academy voters were The Artist and Hugo, two paeans to cinema’s earlier days. While I have no particular argument with them, qualitatively speaking, there can be no denying that the two films likely held high appeal with the elderly and out-of-touch industry insiders voting on them because they themselves were nostalgic, in their own ways, about “going to the movies.” Whether the sheer predictability of their dominance, especially as it pertains to The Artist, informed the show’s presentation, I know not (though I strongly suspect it did). Nonetheless, it only added to the overall perception that this year’s Oscars was entirely driven by a desperate pained nostalgia.

The favor shown toward "The Artist," the predictable winner of the Best Picture Oscar and four others, was eerily indicative of the nostalgic yearning for the simplicity of cinema's past that defined this year's awards ceremony.

Why should the act of “going to the movies” in the present context seem almost nostalgic nowadays? This last year, the movie theater attendance reached a sixteen-year low. Now, it would be asinine to ascribe this decline to any one reason. The basic absence of strong product in the realm of higher-end, high-yielding blockbuster films was very much a leading culprit, with only the final chapter of the Harry Potter series and yet another god-awful Transformers movie really making any significant impact on the box office (and in those cases their tallies were inflated by 3D ticket prices). Mid-range films also seemed unable to make too much of an impact, with their viability diminished by high price stars and honestly mediocre quality. It can’t be denied, though, that emerging digital technologies have also marginalized profits by drawing people away from the theater. Downloadable films have not yet equaled the proliferation that DVDs (also declining rapidly) achieved at their zenith, and new forms of subscription streaming services are defined by licensing deals that split profits across overall libraries of films, not individual titles. Of course, a chief issue remains illegal downloading through torrents and the like: all readily available to tech-savvy (or even only partially tech-savvy) consumers sitting at the forefront of online video viewing. Illegal piracy is undeniably costing the industry millions a year; combined with their other revenue streams constricting at a noticeable rate, it’s understandable that the industry would try to use its biggest, highest profile yearly commercial to sell the one thing it does still control: the movie-going experience.

While not quite this bad, movie attendance was down in 2011 to the lowest point since 1995...

Really, it wasn’t hard to see this underlying tension at play in the Oscar telecast this year, but it was almost sad seeing the movers and shakers in the motion picture industry almost begging their declining audience of older viewers to keep paying escalating ticket prices to see movies in the theater. Outside of trying to remind people of how great movies were (yes) and are (supposedly), there were moments on the telecast that seemed acrimoniously directed at both audiences and artists alike, questioning them for their role in their industry’s uncertain condition. In what, admittedly, might have been one of the evening’s few highlights, Christopher Guest and his regular troop of improvisation performers filmed a skit lampooning film focus groups, satirizing how badly the suggestions of such a group would have destroyed a classic film, which, within the sketch in question, was The Wizard of Oz. Though funny, there was a clear message: if you audiences don’t know what you want, how are we supposed to give it to you? Even during Crystal’s now painfully hackneyed song-and-dance number he and his writers apparently felt it necessary for him to walk over to director Martin Scorsese, nominated for Hugo, and beg him to go back to making the kind of full-blooded gangster movies he used to (the exact joke, in fact, involved Ben Kingsley getting shot in the back of the head…classy). The message again, was clear: despite the fact that Hugo was a critical darling and went on to win five Oscars later in the evening, it wasn’t what audiences wanted to see; the film has to earn back its sizable price tag. Goodfellas never had that problem, right? “So please, Marty, go back to making that…we can even do a reboot if you want!”

Billy Crystal's song-and-dance routine at the Oscars included a noticeable shot at Martin Scorsese that half-jokingly begged him to go back to making the gangster movies he was better known for.

Of course, the real problem with Hollywood extends past its audiences and even past its artists. The industry finds itself trapped in a weird space, right now, between its past and its future, and the only thing they’re clearly sure of now is the recent past. For the last five years or so, the studios in Hollywood found themselves benefiting from a number of key revenue streams and, as a result, became somewhat complacent. The international marketplace grew by leaps and bounds, making the domestic marketplace less significant than it had ever been. Home media, newly imbued by high definition Blu Ray, only added to the bottom line. As a result, a very extraordinary thing happened: Hollywood became virtually market-proof. Even as the costs to produce and market films grew, it became difficult for many mid-range films to actually “bomb” to any significant degree. If a movie did badly in theaters domestically, it could make it up internationally; if it ultimately failed theatrically, than it could make it up on DVD or by licensing it to television. Forced into having to make their product “internationally acceptable” and without the invisible hand of the free market to dictate quality, Hollywood movies, even when technically “good,” have grown repetitive, unintriguing, and usually bland, constructed to be no more sophisticated than what can be processed by the average pre-teenage intellect and defined more by what could be franchised instead of pursuing the original ideas that the industry was once forced to exploit from time to time to keep things fresh.

Mainstream moviemaking is in no danger of going the way of the dodo any time soon; big movies are still extremely profitable, and sometimes still very good. Never in my lifetime, though, has the cinema seem more tired and less relevant than it has the last few years, more out of touch, and less capable of influencing the cultural landscape. The Oscars, naturally, demonstrated this in spades, but really, it’s everywhere you look: movie stars are still celebrities, but there are fewer and fewer that get their names above the title, so to speak, and more and more they share their celebrity status with those who are celebrities for no reasons of actual merit – call it the Kardashian effect. And the movies themselves, even the best of them, are lucky to have more than a week or two in theaters before they’re displaced by the next, easily forgotten product.

While "Avatar" made billions and paved the way for more widespread use of 3D, its cultural footprint ended up being fairly small.

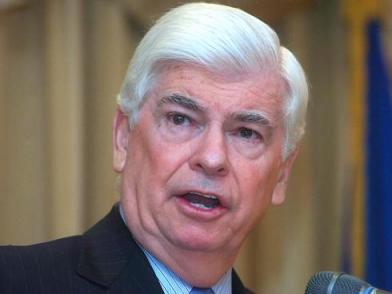

If there was any doubt how far the film industry has fallen in its prominence over a few brief years, you really don’t have to look farther than the recent SOPA and PIPA controversy. Fully backed by the motion picture and television industry (as well as the recording industry and many other providers of media content), both forms of congressional legislation were designed to address the illegal exploitation of intellectual property in online piracy. Despite this noble aim, the legislation was met with heavy resistance driven in large part by search provider Google, online encyclopedia Wikipedia and others, who managed to amass widespread support numbering into the millions. In the face of such a backlash, the supporters of the legislation and allies to the various content industries quickly backed off, leaving the bills to basically fall into limbo. While it might be an oversimplification to say that the Internet defeated Hollywood, it wouldn’t be wrong; when it came down to customers choosing between the Internet and the movies, the movies lost, and lost bad. Instead of being among the chief arbiters of mass media, the motion picture industry suddenly found itself behind the curve of modern technology and those who serve as gatekeepers to it. Worst still, the young, trendy, and hip, those who Hollywood depends on to see the films they produce en masse, came to see the industry as older and out-of-touch, and perhaps worst of all, one of “them” (as opposed to one of “us”).

Former Democratic Senator Chris Dodd, now the chief lobbyist for the Motion Picture Association of America, was the public face of Hollywood during the SOPA/PIPA debacle.

(For the record, I myself opposed SOPA and PIPA, and advertised so on this website’s banner. I did not participate in, nor really agree with, the widespread January blackout spearheaded by Wikipedia; nor do I support the subsequent denial of service attacks by Anonymous. Like many others, I opposed the laws because I found the legislation flawed in execution, if not in core intent.)

In the recent battle between the Internet/New Media and the Motion Picture industry, the movies undeniably lost.

So again, faced with the uncertainty of new media, and this ties back to what was on display at the Oscars, the industry is doubling down on the movie-going experience, in spite of the fact that everything is now in the midst of a major sea change; the effects of which have already been profound. Films aren’t even films in name anymore: something that hasn’t received much mainstream attention during the recent 3D reemergence has been that the upgrading of theater equipment has led to a steady changeover from movies being shown on Mylar film stock to being digital files projected though expensive protection systems. In recent months, the famed film scholar David Bordwell has been writing extensively through his blog on the potential effects of the technological shift toward digital projection, and its costs to both smaller, independent theaters and the overall movie-going experience as we know it. “In our transition from packaged-media technology to pay-for-service technology,” says Bordwell, “parts of our film heritage that are already peripheral—current foreign-language films, experimental cinema, topical and personal documentaries, classic cinema that can’t be packaged as an Event—may move even further to the margins.“

An example of the newer models of high-price digital projectors that have been replacing film projectors across the country and pricing smaller, niche theaters out of the market.

Essentially, as film-viewing changes, certain types of films are going to suffer the most; not the blockbusters or even higher-end “mainstream” films. Already it’s becoming clear that foreign film distributors and independents have been rushing to embrace On Demand and online streaming for their sources of revenue as opposed to relying on the standard theatrical release and home media model. As someone who has been living in the New Jersey suburbs the last few years, despite a growth in the number of actual movie screens in the area, it’s become a lot harder to find theaters that regularly carry foreign and even straight independent films on a regular basis. And even when they do, sometimes the high ticket prices and inconvenience aren’t always worth it; after all, I’m paying for Netflix, Amazon, and other streaming options. Very often, I consciously wait to use them for movies I feel I can wait to see.

Some of the statistics revealed by Bordwell are somewhat discomforting, though. In the face of the technological changeover, “as many as eight thousand of America’s forty thousand screens may close. Their owners will not be able to afford the conversion to digital. Creative destruction, some will call it, playing down the intangible assets that community cinemas offer…Only the permanently well-funded can keep up with the digital churn….In any event, there’s no reason to think that the major distributors and the internet service providers will be feeling generous to small venues.”

Film scholar and historian David Bordwell has recently been chronicling and analyzing the almost unseen changeover from film to digital projection; and some of what he's observed is disconcerting...

Bordwell may be being too pessimistic about things; some statistics have shown that foreign and independent films might be viable as streaming and on demand products, and the Tribeca Film Festival and others have spearheaded new digital methods of distribution for independent films. It’s almost inevitable though, as Bordwell implies, that the smaller theaters are now going to suffer. Film – actual film – isn’t dying, it’s dead, and the venues that still utilize it to show movies can’t for very much longer.

But what about Hollywood and its “Event” products, the ones the Academy Awards try to celebrate every February? It’s hard to say, but I think there’s plenty of writing on the wall, and sadly, a lot of it doesn’t speak well to the idea of the industry maintaining such a heavy focus on its theatrical model. Once again, the cinema isn’t going anywhere, and I’m certain the act of seeing movies in a theater will be around for many generations to come and likely longer. It’s also very probable that the industry is going to do better this year than last due to a bevy of more anticipated products (many of which are sequels, or even worse…reboots). But it’s insipid not to think that things are changing considerably, and that the ways we substantially view movies, especially good movies, aren’t going to be the same going forward.

An example of the cinema of the future? From one of the theaters from the Yelmo Cinema chain in Spain.

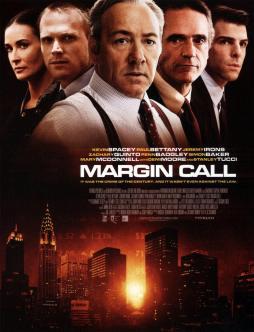

The Tribeca Film Festival, as part of its interest in new forms of distribution, hosts a blog on their website called The Future of Film. In a recent post by David Larkin, founder of the website Go Watch It and CEO of Plexus, he postulated about the escalating divide between the business models and aims of Hollywood and Silicon Valley. It’s an intriguing read in total, but among his major observations is that Hollywood essentially works to set up expensive barriers to its content: you must buy a ticket, rent a disc or download, or spend a fair amount to actually own a film for repeated viewing. Online, of course, the aim is different – to get content to the audience that most wants it, as quickly, directly, and inexpensively as possible – which is part of the main philosophical conflict between the two mediums. Of course, the reason for the industry’s expensive barriers is that Hollywood’s product model is an expensive one; movies essentially have to make astonishing sums of money to justify their existence thanks to their high production costs, leaving Larkin and some of his Silicon Valley acquaintances to wonder if Hollywood wouldn’t be better served trying to steadily move in the opposite direction. As an example, he used Margin Call, one of the best films of last year, as a comparatively inexpensive adult drama with little mainstream marketability that was released to On Demand the same time it appeared in theaters, a trend that is becoming more and more common (and can viewed in recent weeks with the roll out of Tony Kaye’s Detachment).

"Margin Call," one of the better films of last year, was one of the most high-profile examples of a film released to On Demand and theaters simultaneously, challenging the older pattern of theatrical release followed by home media distribution.

For my part, one of the reasons that led me to find the Academy Awards somewhat depressing given all this, is that despite my entire love/hate relationship with Hollywood and its product, I do love the cinema and want to see it survive and thrive on as many levels as possible. The Oscars, though, explicitly demonstrated a Hollywood out of touch and looking toward the past with its business model, uncertain of the future in the face of changing technology. Its only response in this instance was to lash out at its audience and its artists, and desperately try to remind us why we’re supposed to love the movies. Of course, as events like PIPA and SOPA have demonstrated, they don’t seem to realize that they’re no longer the ones dictating the terms of that romance. We, the audience, are, and the terms are that we’re looking for are good movies that we can watch at our convenience, within our price range, and in the manner we think is best for that product. It’s a tall order, though, and right now, it’s clear that Hollywood doesn’t really know how to satisfy it as well and as easily (if often illegally), as the Internet does. The other reason, perhaps obviously, was that in desperately trying to market nostalgia for going to the movies, the Oscars were a painfully nostalgic reminder that going to the movies just isn’t, as Bordwell has emphasized, the community-building experience that they used to be. The experience is now mass-produced, digitized, canned, and ordinary: an act of consumption, not the experience Hollywood’s best and brightest either eloquently or ineloquently tried to invoke three weeks ago. Given that, it’s no wonder more and more people are watching movies at home on their television or computer. It’s more or less exactly the same experience now, just for less money, no matter how many movie stars Hollywood parades out trying to tell them otherwise.