I wrote this for my MatadorU travel writing course, and thought it would be fun to share here. It’s about some of the field work I was doing while I was in South Carolina last year.

—

When I leave the house in the morning it is dark enough to use the brights. I drive my truck along a paved road, which turns to dirt. The packed dirt is first tan, then reddish-orange, then almost white. A nightjar stares me down from the middle of the road, but as I slow it flies off into the dark.

———————————————————————————————–

A red-cockaded woodpecker foraging in a pine. Note the black and white barring on the back, white cheek patches, and black hood. The males will have small red patches on the back of their heads, which typically can’t be seen unless the bird is riled up and raises its feathers.

———————————————————————————————–

The dark is softer when I arrive at Compartment 20, my destination. I wait in the truck, drinking tea from my thermos and listening to the radio, until the sky lightens. Just before sunrise I take one last sip and then slip into place with my spotting scope, binoculars, and notebook. I position myself about 100 yards from the nearest cavity tree and wait. The cavity I’m watching, a dark hole about 25 feet off the ground, partially hidden between branches, looks lifeless.

After ten minutes I see what I’ve come for: a red-cockaded woodpecker (RCW) bursts out into the morning, chattering loudly. It forages in a nearby tree, tapping here and there on the bark, flaking off pieces that swivel to the ground. After a few minutes another RCW joins, and the two flit from tree to tree calling and foraging, taking stock of the day.

Fully grown, an RCW is the size of a robin with black and white stripes running across its back, sometimes called a ladder back. Like clowns, they have giant white cheek patches and tiny black caps. The males have red cockades, or small red patches, on each side of their black caps.

I follow the pair for the better part of an hour before I leave them to their business. Back at the truck I take a sip of now-cold tea before reading through my notes. Both RCWs were unbanded, which means they had not been captured and fitted with aluminum USGS numbered bands or colored plastic bands, which we use to identify individual birds. Because there were just the two of them, they are most likely a potential breeding pair, or a pair of mated RCWs who for whatever reason didn’t nest this year.

I was out this morning doing an early morning nest check, observing what was going on in a particular cluster of RCW cavity trees. These checks help to determine the overall breeding status and size of the RCW population on the refuge. They also mean that I get to spend early mornings in the woods staring at trees, hoping birds will show up so I can follow them and see what they’re up to.

—

In 2012 I spent three months as an endangered species intern, studying RCWs with the biologists at Carolina Sandhills National Wildlife Refuge. My internship, arranged through the Student Conservation Association, provided me with the opportunity to do hands-on conservation biology and work with government biologists to study an endangered species, a bird that few have heard of, let alone seen. My background in biology, and specifically ornithology, the study of birds, has taken me around the country to different wildlife refuges and protected areas, where I’ve had the privilege to experience many different aspects of the natural world.

Carolina Sandhills is located just outside of McBee, South Carolina, which is located just outside of the middle of nowhere. As a local intern explained to me, towns in the region are defined by whether or not they have a Wal-Mart. McBee does not have a Wal-Mart.

———————————————————————————————–

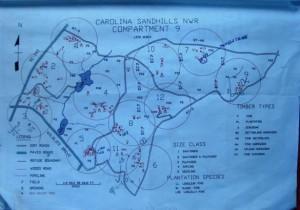

Carolina Sandhills NWR is divided into 21 compartments; each typically has 10-12 clusters of cavity trees. The maps give us an approximate idea of where the trees are, and we then find them on foot using a compass and a large dash of intuition. It sometimes took a while to find particular trees, as the maps are not entirely accurate.

———————————————————————————————–

Red-cockaded woodpeckers (Picoides borealis) have been on the endangered species list since 1970, and the current population is estimated to be about 12,500. Like many endangered species, RCWs are closely tied to their habitat, in their case the longleaf pine ecosystem. There once were about 90 million acres of longleaf habitat spreading across the eastern United States, from New Jersey south to Florida and west to Texas, Oklahoma, and Missouri. Only 2 million acres remain, in mostly isolated patches scattered through the southeast.

That much ecosystem doesn’t just disappear on its own. Logging, agriculture, the turpentine industry, tree farming, and urbanization, along with the suppression of natural fires, contributed to the decline of longleaf pine. Of these, burning is perhaps the most critical, because when fires are suppressed the composition of the forests changes. Fewer fires promote the growth of hardwoods, which the RCWs have no use for. They need pines, and pines need fire.

Natural fires, caused by lightning strikes, are typically low-intensity burns. These fires incinerate the fallen needles and grasses and leave mature trees undamaged. This keeps the area around the longleaf cleared, reducing competition and providing open areas for their seeds to quickly absorb nutrients from the ash. Longleaf pine forests are typically composed of just longleaf; there is an obvious lack of mid-story trees. The ground is covered with a high diversity of plants, all of which benefit from fire as well. Frequent forest fires “acted as the thread which held the longleaf pine forest together (1).”

RCWs are the only woodpeckers that nest in living pines. Connoisseurs, they prefer their trees aged: old-growth longleaf pine being most favored. The best longleaf will have red-heart disease, which softens the heartwood enough for the birds to easily excavate a cavity, anywhere from 10 to 80 feet off the ground. Longleaf pines have a high resin yield, and are very sticky trees. RCWs will open up sap wells all over the tree, which are especially good at keeping away rat snakes that will try to climb up and eat their eggs and nestlings. It is easy to spot cavity trees once you know what to look for—a large reddish section of bark midway up the tree, encrusted with sap.

Biologists (and interns) monitor most of the trees on the refuge with cavities, of which there are over 1,300. Thankfully, we only need to monitor the ones with recent activity, about a third of the cavity trees. The refuge is 45,348 acres, so there is a great deal of driving and hiking involved in this line of work.

—

Later in the morning, I drive to the office to fill out the official observation form for Nancy, the refuge biologist. Grabbing up my notebook and the spotting scope, I head inside.

“So how did it go out there?” Nancy asks.

“I had two. They stayed mostly in Compartment 20, then headed towards that farm across the road off the refuge, then back towards Compartment 21.”

“That’s interesting; I wonder why they went over there. Ok, good. I thought I had heard birds out there during nest checks. Did they have bands?

———————————————————————————————–

My peeper, leaning on a marked cavity tree. All known cavity trees are marked with a broad band of white paint to help not only biologists but also the firefighters who set prescribed burns on the refuge identify them. Peepers are about five feet tall and extend up to 35 feet.

———————————————————————————————–

“Nope, both unbanded.”

“What trees were you watching?”

“I was set up on 93, and the first RCW came from the cavity near the top of the tree. The other came from behind me, probably 97.”

We talk a little more about details of my observations, and Nancy shares her morning experiences in a different compartment. I fill out the official observation form, and she gives me my instructions for the day. I have five trees to inspect, checking up on nestlings we banded about two weeks ago.

“How’s your peeper been working?” she asks. Peepers are cameras on telescoping poles, which we use to ‘peep’ into RCW cavities. They keep us from having to climb the trees so we can make our observations more quickly, which means less stress for the birds, though not always for us. RCW cavity openings are about 2 inches in diameter, and directing a camera head smaller than your fist into a 2 inch hole 30 feet or so above the ground takes a bit of skill and practice. As a rule, the sun will be in your eyes, it will be windy, and/or there will be branches in the way.

“Okay I guess, but sometimes the arm that holds the camera up doesn’t stay tight, so when I pull it out of the cavity it flops straight down, and then I have to lower the entire thing and re-adjust it if I need another look, which is a pain.”

———————————————————————————————–

A RCW nestling, about 7 or 8 days old. Its eyes are unopened, and the feathers are just starting to come in and poke through the skin. Their feathers grow in tracts, the darkened areas on the bird’s head, back, and wings. It takes RCW’s about 20 days to become fully feathered and reach adult size.

———————————————————————————————–

Woodpecker nestlings are altricial, which means they are born without feathers, eyes closed, and are pretty much helpless. It takes about 20 days for RCW nestlings to grow in their adult feathers. Juvenile males will have the distinctive red crown patches on their temples; females’ just plain black and white. I peep into cavities and look for splotches of red, jotting down the number of nestlings and their sex: male, female, or unknown, if they are being uncooperative and sitting on top of one another so I can’t see the back of their heads.

As I drive off through the refuge towards my first cavity, I hear the chatter of brown nuthatches in the pines to my left. They sound like so many squeaky toys, jumping around in the trees like little yippy dogs. Listening closely, every once in a while I hear the “sklit, sklit” of an RCW flying overhead.

———————————————————————————————————————-

1. Auburn Forestry site: The Longleaf Alliance

Additional Information

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Red-cockaded Woodpecker Pamphlet

- Carolina Sandhills National Wildlife Refuge

- My internship was made possible through The Student Conservation Association

Blog posts about my experiences: