Many Stanley Kubrick films exist more as cerebral exercises than entertainment. Thus A Clockwork Orange (1971), which inundates viewers with ugliness posing as satire. Thanks to warped imagery and Malcolm McDowell's acting, Kubrick nearly pulls it off.

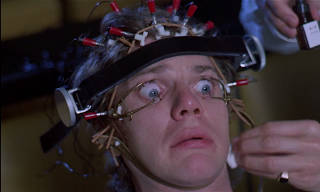

Many Stanley Kubrick films exist more as cerebral exercises than entertainment. Thus A Clockwork Orange (1971), which inundates viewers with ugliness posing as satire. Thanks to warped imagery and Malcolm McDowell's acting, Kubrick nearly pulls it off.Teenaged hooligan Alex DeLarge (Malcolm McDowell) wreaks havoc across dystopian London with his gang of "droogs." Their crime spree comes to a halt when Alex inadvertently kills a victim and is arrested. Alex survives two years in prison, then volunteers for the experimental Ludovico treatment, meant to cure his violent impulses. The treatment works too well, leaving Alex a traumatized vegetable at the mercy of vengeful victims.

All Kubrick films are directorial marvels, and A Clockwork Orange is no exception. From its opening close-up of Alex tracking through a crowded milk bar, Kubrick and cinematographer John Alcott utilize long takes, off-kilter close-ups and spacious compositions. Shots of Alex stomping through the smoky streets resemble 2001's lunar scenes, matched with gross art direction. Sets bristle with sex images or rococo furnishings, down to Alex's mom (Sheila Raynor) sporting hair dye and pastel costumes.

Adapting Anthony Burgess's novel, Kubrick treats Alex as the ultimate antihero. He's a psychotic extension of the cinematic rebel, lashing out aimlessly against society. His rapes and killings contrast with a sterile, materialist welfare state who hopes to enslave undesirables. Alex's treatment reduces him to a cringing, asexual zombie who laments losing Beethoven above all. Clockwork insists society can only cure criminals by removing their humanity, where sex, violence and art coexist.

Malcolm McDowell ensured immortality with this performance. His mascaraed eye, sinister sideways glance and jaunty narration render Alex an iconic antihero, but McDowell insists on probing deeper. His calculating nastiness gives way to insecurity and forlorn submissiveness. That we sympathize with Alex at all is an achievement, but McDowell's intense, wry performance makes him unforgettable.

Unfortunately, Clockwork's devoured by hysteria, everything conveyed through crushingly obvious symbolism. Alex smashing a victim with a plaster phallus renders Dr. Strangelove's innuendos anodyne. Walter Carlos's thudding score clashes with classical music, used for obvious irony. Alex's fast motion threesome generates laughs, but the rape and brawl scored to Rossini is sickly cute. It's like Kubrick screaming repeatedly at us, as if we're witless malchicks.

Unfortunately, Clockwork's devoured by hysteria, everything conveyed through crushingly obvious symbolism. Alex smashing a victim with a plaster phallus renders Dr. Strangelove's innuendos anodyne. Walter Carlos's thudding score clashes with classical music, used for obvious irony. Alex's fast motion threesome generates laughs, but the rape and brawl scored to Rossini is sickly cute. It's like Kubrick screaming repeatedly at us, as if we're witless malchicks.This rococo aesthetic may account for the awful supporting cast. Patrick Magee and Michael Bates are the worst offenders; playing Alex's main victim and a sadistic prison guard, they shout and goggle like dinner theater rejects. Aubrey Morris's jabbering probation officer and Philip Stone, as Alex's ineffectual father, fare little better. It's possibly the worst acting you'll see outside of an Ed Wood movie.

Orange's politics often resemble reactionary driveling about modern decadence. Hence the Russian-inflected nasdat slang, pervasive pornography, pathological youths, overweening state socialism. Officials declaim crass motivations in long exposition speeches, Alex fantasizes about violence when not committing it. Brushed with Kubrick's trademark nihilism, Orange becomes less clever than crapulent.

Like its protagonist, A Clockwork Orange is a conundrum, mixing great art with violent excess. Perhaps if Groggy sufficiently jimmied his rasoodock, he could embrace the latter as Kubrickian brilliance. Until I'm so enlightened, I'm satisfied with wary respect.