Introduction

Few works in the history of popular culture have had as much pronounced effect as Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, first published in 1843. While Christmas Day had always been a sacred, solemn feast day within the Christian faith (just as the Winter Solstice had been in many pagan cultures before it), it wasn’t until the middle part of the 1800s that many began to see it less as a site of religious devotion than as a holiday to be celebrated, and to be celebrated most specifically through the act of giving. While A Christmas Carol didn’t spawn this tradition itself, it, more than any other force, popularized it throughout the western world. Through its powerful, secular story of redemption through charity and love, Dickens imparted to all that Christmas was a time to celebrate all that was worthwhile about the human race, most specifically our love for one another, and our compassion for those less fortunate.

A Christmas Carol, of course, relates the story of Ebenezer Scrooge, a malevolent, miserly moneylender of old London grown embittered by a life devoted more to money than his fellow man, and how the nocturnal visitations of three Spirits of Christmas compel him to not only amend his ways, but become a paragon of charity and kindness “who knew how to keep Christmas well.” Through the tale of Scrooge comes the empowering, heartwarming lesson that no person, no matter how broken by the either themselves or the harshness of the world, is beyond hope of redemption, and that true happiness is defined less by what we take from the world, than what we give to it.

Beneath that, though, A Christmas Carol is also social critic Charles Dickens’s scathing critique of unchecked capitalism and self-obsession, and a powerful reminder that a life devoted only to the accumulation of wealth or power is not without its collateral damage. Though a timeless work, A Christmas Carol was still a work of its time, a time when the mad rush of Victorian industrialization left many behind without hope of finding a better life, and great wealth became more and more consolidated with those who had the power to influence and affect the lives of many other souls. While some of Dickens’s implied messages, such as the idea that the success of the struggling working classes are solely incumbent on the benevolence of the wealthy, can be highly problematic, his central plea, that when some of us suffer, so suffer we all, remains as true today as it did in 1843.

It should go without saying that whether it’s due to its timeless message, endless popularity, and/or boundless influence, A Christmas Carol has proven to not only be a ready source for adaptation in the worlds of film and television, but one of the most popular. Many great actors through the decades, on both stage and screen, have tried to make their mark on Ebenezer Scrooge’s enduring legacy, and since 1901 (and perhaps earlier), many great filmmakers have interpreted and reinterpreted the story, time and again, helping to impart its message to each new generation. Now, this is usually the time in these Overviews where I point out that “some were better, and some were worse,” but for the most part, A Christmas Carol is a hard story to get wrong, so I’ve largely forgone that approach to this piece. Also, since A Christmas Carol is one of the most oft-filmed stories in the history of the moving image, I’m generally limiting my scope to versions which I feel are the most significant and most popular, and those are usually the best versions anyway…though there are exceptions, of course.

Finally, for this overview to have any significance, you must remember that Jacob Marley was as dead as a doornail. And with that, away we go…

Scrooge (1935)

Though creaky and stilted by modern standards, this British-made talkie version is not without its significance: besides being the earliest surviving sound adaptation of A Christmas Carol, it also provides an interesting glimpse at London theater icon Seymour Hicks’s take on Scrooge, a role he had been playing onstage annually since 1901 (Hicks also starred in an earlier film version of the story in 1913, also titled Scrooge). As a film, Scrooge isn’t much, and it suffers from a very low budget – so low a budget, in fact, that Jacob Marley’s ghost is portrayed as “invisible.” Hicks’s Scrooge is also a very singular interpretation, yet it will probably not be for all tastes. If you do watch it, make sure it’s the recently remastered 78 minute version, and not the more common hour-long version, which not only severely truncated the story but has such visual and audio issues it often proves unwatchable.

Scrooge Trivia: Though an unknown quantity for many modern audiences, Sir Seymour Hicks is notable in film history for giving a young Alfred Hitchcock his first credit as a film director with 1923’s Always Tell Your Wife (for which he is credited as co-director with Hicks).

A Christmas Carol (1938)

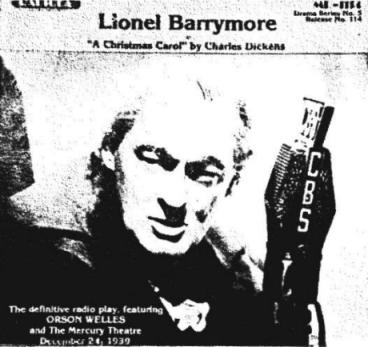

Back in the 1930s, there was one actor who was synonymous to the American public with the role of Ebenezer Scrooge, and that actor was the great Lionel Barrymore. A member of the legendary Barrymore family (Drew is his grandniece), Lionel had played Scrooge live on the radio nearly every year between 1934 and 1953. Given the tremendous popularity of Barrymore’s Scrooge, making a film version of his performance seemed inevitable, and in 1938 MGM planned to do just that with their own version of A Christmas Carol. Unfortunately, Barrymore, recovering from a broken hip at the time, could not accommodate MGM’s shooting schedule and therefore the role of Scrooge went to that of longtime British character actor Reginald Owen. Now, if you’re reading this and asking yourself “who’s Reginald Owen?” then rest assured, many in 1938 were doing precisely the same thing.

MGM’s version of “A Christmas Carol” was a conversation starter. Of course, that conversation’s always started with: “Who’s Reginald Owen?”

Hurriedly shot in a few weeks in October 1938 for a December release (God bless the studio system), this was, for decades, the most widely seen film version of A Christmas Carol in circulation; since the 1970s, though, its popularity has markedly declined in favor of other versions (most notably the later Alistair Sim film), and it’s really not hard to see why. All told, this stands as a remarkably lackluster version of the story, defined by uninspired casting, starting with Owen’s rather tepid and caricatured Scrooge, and unaided by Gene Lockhart’s Bob Cratchit (his wife Kathleen played Mrs. Cratchit, and daughter June was uncredited as one of the Cratchit children). Not helping matters was that the film is highly sanitized, with many of the darker, spookier elements of the original story excised and, by proxy, a significant amount of its social conscience. And naturally, this being a MGM production, they also tried to shoehorn in a romantic subplot where it absolutely did not belong.

While Lionel Barrymore’s famed Scrooge never made it to the silver screen, many audio recordings exist, including this version performed with Orson Welles’s Mercury Theater Company.

Fortunately, while Barrymore’s Scrooge was never really captured on film (though several audio versions of it exist), many elements of his performance were later immortalized in Frank Capra’s seminal It’s a Wonderful Life, where Barrymore played another villainous, curmudgeonly miser: the nefarious Mr. Potter.

Scrooge Trivia: Though best known now as kind of a footnote in terms of celluloid Scrooges, Reginald Owen had a career as a character actor in Hollywood that lasted decades; he’s also notable for being one of the few to ever play both Scrooge and another Victorian literary icon, Sherlock Holmes, which he did in the 1933 film A Study in Scarlet (it’s worth mentioning, however, that he didn’t do a very good job in that, either).

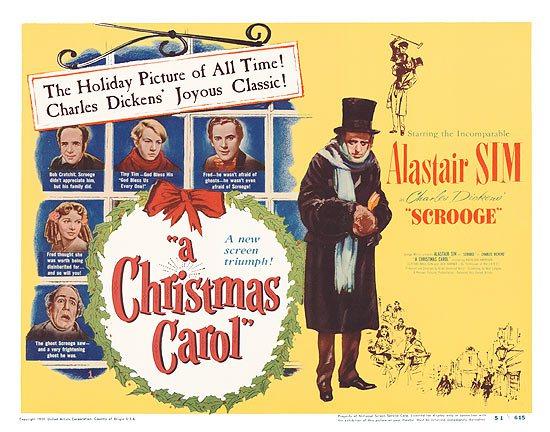

Scrooge (US title: A Christmas Carol) (1951)

There’s probably not much I can add about this film, which is rightfully considered by many to be the best of the manifold film versions of A Christmas Carol, in no small part because it features arguably the greatest Scrooge of all time. Played to perfection by the actor and comedian Alistair Sim, Ebenezer Scrooge here wasn’t portrayed as the broad, often two-dimensional caricature he had been many times before and since. With his Scrooge, Sim wasn’t aiming to give the world another inhospitable miser being cruel for cruelty’s sake, but an unhappy man whose coldness to humanity was drawn from some deeper sorrow. To that end, this version, written by Noel Langly and directed by Brian Desmond Hurst, embellished much of Scrooge’s backstory well beyond what was in Dickens’s novella, granting its audience a far better understanding of what made this Scrooge into such a…well, Scrooge. As a result, it not only makes Sim’s Scrooge a far more compelling individual, but his ultimate transformation into a good man all the more cathartic.

Alistair Sim’s Scrooge was less a cruel miser than a miserable man, making him a character we genuinely wanted to see change.

In addition, Hurst and Langly also restored to the story all of the atmosphere and supernatural malevolence that the earlier MGM interpretation removed, to such a degree that its original New York City engagement at Radio City Music Hall was scrapped on the basis of it being “too sinister” for a broader family audience. To that end, while Scrooge was very popular in Britain during its original release, the film went largely overlooked in the United States until being gradually rediscovered through seasonal airings on PBS and syndicated stations in the 1970s. For many it now stands as the definitive film version, with every Scrooge performance since essentially standing in the shadow of Sim’s iconic interpretation.

Scrooge Trivia: This film’s editor, Clive Donner, would later go on to direct the exceptional 1984 version with George C. Scott.

Mister Magoo’s Christmas Carol (1962)

Historically notable as the first animated Christmas special in television history, and thus the forerunner of such holiday classics as A Charlie Brown Christmas, this hour long adaptation of the novella is fondly remembered by many of its generation and often shows up on lists of many people’s favorite versions of the Dickens novella (it also proved to be the forerunner for generations of animated characters doing their own versions of the story at one time or another). Starring UPA animation’s Mr. Magoo character (voiced by comedian Jim Backus, AKA Thurston Howell III on Gilligan’s Island), a wealthy and loveable eccentric who stubbornly refuses to acknowledge his nearsightedness, this employed a clever play-within-a-play variation on its presentation of the tale, with Magoo portrayed as playing the lead in a Broadway musical version of the Dickens story. A pleasant watch with some surprisingly good songs, written by Jule Styne and Bob Merrill, and enjoyable even for those completely unfamiliar with the Magoo character. Surprisingly, many Dickens buffs also hold this version in high regard for presenting much of the novel’s original dialog intact instead of “modernizing” it, as many other versions do, for a then-contemporary audience. Originally aired on NBC in 1962, the network just acknowledged its 50th anniversary by airing it in prime time recently for the first time in more than forty years (though it badly cut down much of its original running time to allow for commercials).

Scrooge Trivia: Besides being a quality version of Dickens’s story, Mr. Magoo’s Christmas Carol also offers a fair representation of the animation style of the UPA studio, whose considerable work is often overlooked these days due to the enduring popularity of Disney and Warner Bros. Notable for their intentionally minimalistic animation, the studio received two Oscars in the 1950s for the shorts “When Magoo Flew” (1955) and “Magoo’s Puddle Jumper” (1956), and the popularity of this special led to the well-remembered series The Famous Adventures of Mr. Magoo.

Scrooge (1970)

My personal favorite of the many musical versions of A Christmas Carol, this version sometimes gets derided in some circles due to Albert Finney’s polarizing performance as the heartless miser (for which he won a Golden Globe). I personally enjoy both the film and the performance, though I see why some have a problem with the latter; at only 34 years of age at the time, Finney was among the youngest to ever play the role, and as a result his Scrooge ventures into being a caricature of an old man. Despite that, I think this version did among the best jobs among all interpretations at developing Scrooge’s character change over the course of the story, and Finney especially does a great job when playing the younger, tragic Ebenezer in the “Christmas Past” portions. It also has a pretty terrific assortment of songs, including “I Like Life,” “I Hate People,” and “Thank You Very Much.”

Scrooge Trivia: Besides Finney’s Golden Globe-winning performance, Scrooge was nominated for four Academy Awards, the only live-action version of the story to ever receive Oscar nominations.

A Christmas Carol (1971)

This criminally underseen version of the story may also be the all-time best. Directed by the great animator Richard Williams and co-produced by the legendary Chuck Jones, this brilliant animated adaptation could be among the best cartoons ever aired on American television. Visually audacious and breathtakingly evocative, this Christmas Carol featured Alistair Sim reprising his famed interpretation of Scrooge, with narration by Michael Redgrave, and it did an exceptional job parsing Dickens story down to 27 minutes without sacrificing any of its power. Truly a must see work, especially for animation buffs; this was so well-regarded that it was given a theatrical release after airing on ABC in 1971, which, due to Academy loopholes at the time, made it eligible for the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Subject, which it won handily in 1972 – making it the only version of A Christmas Carol to win an Oscar, ever.

Scrooge Trivia: Though a famed animator and winner of two Oscars (the second for the animation effects in Who Framed Roger Rabbit?), Richard Williams is perhaps most famous for a film he didn’t finish: The Thief and the Cobbler, which Williams worked on intermittently for twenty-eight years beginning in 1964. Sadly, the film was taken out of his hands by a completion bond company in the early 1990s, finished by others, musicalized, and somewhat inauspiciously released in various countries under the titles The Princess and the Cobbler and Arabian Knight, where it was quickly forgotten. Though the original work still stands as incomplete, what was completed by Williams and his collaborators is often highly regarded by several observers as some of the best animation ever placed on film. Not surprisingly, it also holds the Guinness Record for longest film production in history.

Mickey’s Christmas Carol (1983)

It shouldn’t be at all shocking that the Walt Disney Company would someday try to put their own stamp on the Dickens classic; what’s probably most surprising is that it somehow took them so long to do it. First released theatrically with a reissue of Disney’s The Rescuers, this went on to become a holiday staple on network television throughout the 1980s, and it airs annually on Disney cable channels to this day. A pleasant enough version of the story and a huge treat for Disney fans, as it boasts appearances from most of Disney’s rich line-up of classic characters in both key roles and cameos, with Jiminy Cricket as the Ghost of Christmas Past, Goofy as Jacob Marley, Mickey himself as Bob Cratchit, and (of course) Scrooge McDuck as Ebenezer Scrooge. In fact, the popularity of the show’s original network airing was such that it led Disney to take a renewed interest in producing animated work for television, the first of which was the wildly popular and well-remembered DuckTales, which centered on the misadventures of none other than Uncle Scrooge himself.

Scrooge Trivia: Though Mickey Mouse is synonymous with the image of Disney (and essentially their corporate mascot), Mickey’s Christmas Carol actually represented his first original animated work in thirty years. It was also the final time that Clarence Nash, the original voice-actor for Donald Duck, would perform that character.

A Christmas Carol (1984)

One of the most highly regarded versions of A Christmas Carol, this handsome and very atmospheric adaptation featured George C. Scott as an extremely believable and grounded Scrooge, with an excellent supporting cast that featured David Warner as Bob Cratchit, Roger Rees as Scrooge’s nephew Fred, Frank Finlay as Jacob Marley, Angela Pleasance as the Ghost of Christmas Past, and an excellent Edward Woodward as a particularly judgmental Ghost of Christmas Present. Though I personally feel the two earlier Sim versions represent the best Carols ever, this one absolutely gives them a run for their money in that argument, with a very literate and moving script by Roger O. Hirson that pays more heed to Dickens’ original message about the importance of social welfare than most versions do. It’s also undeniably the scariest version of the story yet produced, with a Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come sequence that’s positively ominous.

Scrooge Trivia: In many respects, George C. Scott may have been an ideal choice to play Scrooge: though among the best-regarded stage and screen actors of his generation, Scott had a far-reaching reputation as being a demanding and moody actor who could often prove an intimidating presence for many of his co-stars. He’s also infamous for having refused his Oscar for Patton on personal grounds, one of only two actors (the other being Marlon Brando) to ever to do so.

Scrooged (1988)

A high profile attempt to modernize A Christmas Carol for the 1980s (and cash in on star Bill Murray’s popularity from Ghostbusters), this somewhat ambitious but ultimately unsuccessful movie is perhaps better remembered than it deserves thanks to some quotable lines (such as permanently affixing Sir John Houseman with the dubious honor of “America’s favorite old fart”). Murray stars as Frank Cross, a heartless, self-absorbed, and unhappy executive for a major television network that’s producing a garish new version of Scrooge (“…featuring the Solid Gold dancers!”) who is encouraged by three particularly grotesque and unfunny Ghosts of Christmas to stop being a complete schmuck to just about anyone and everyone. Besides retelling the story as a widely uneven supernatural black comedy, this also tried to satirize both eighties self-absorption and the entertainment industry’s crass attempts to commercialize everything; unfortunately, the movie itself proves to be little more than a crass commercialization of Dickens, which doesn’t really give it much of a leg to stand on in either the long or short run. It’s a pity, actually, because if there was ever a period of time that could have used A Christmas Carol all its own, it was the “Me” decade. Murray’s delivery and charm carries this one a long way, but the film generally wastes a terrific supporting cast, which included Robert Mitchum, Alfre Woodward, John Forsythe, Bobcat Goldthwait, Carol Kane, and, of course, John Houseman.

Scrooge Trivia: The “favorite old fart” line was actually a source of some controversy at the time as being somewhat disrespectful to Houseman. Capping a sixty-year career as actor, director, screenwriter, executive, corporate spokesperson, and producer of both stage and screen (including a famous though volatile period of collaboration with Orson Welles), Scrooged was Houseman’s final film role, and was released just a few weeks after he passed away on Halloween, 1988. Given its proximity to his death, and that Houseman was making a cameo as himself, some at the time felt the Murray’s sarcastic put-down should have been excised. On the other side, Houseman reportedly found the label to be a rather humorous compliment

A Blackadder Christmas Carol (1988)

Given it’s prominence in popular culture, A Christmas Carol has certainly been spoofed countless times, though few have been as successful as this BBC special – a one-shot installment of the famed Brit-com Blackadder, which chronicled the nefarious exploits of the vile and disreputable Blackadder family over various generations of British history. Played in all his incarnations by Rowan Atkinson, Blackadder was a conniving villain with a scathing wit who was perpetually scheming, unsuccessfully, for more wealth and/or power. The big joke, here, though, was that Ebenezer Blackadder is the only member of the line to be, not only a nice person, but the kindest in all the land (meaning he’s pretty much a living doormat to everyone he knows). Naturally, a run-in with the Spirit of Christmas (Robbie Coltrane) and a glimpse into the lives of his ancestors and descendents teaches him a true Christmas lesson: that bad guys have way more fun. A one joke premise, for certain, but a clever, funny joke supported by the series’ typically biting humor; with that said, that humor is often brutally sarcastic and mean spirited, and therefore may not be everyone’s idea of holiday entertainment.

Scrooge Trivia: While A Christmas Carol has been endlessly exploited as source material for many shows and series’ “Christmas specials,” Dickens himself attempted to capitalize on the popularity of his own masterpiece by producing many similarly-themed Christmas stories in the years following, such as The Chimes and The Battle of Life. While they were popular in their time, they’re mostly considered literary afterthoughts now, and even Dickens held some of them in very low regard.

The Muppet Christmas Carol (1992)

Probably the best remembered version of Carol to my generation, this delightful take saw Dickens getting the singular Muppets treatment (literally, in fact…Gonzo the Great himself plays the great author). Equally parts hilarious and heartwarming as only the Muppets could really pull off, anchored by a tremendous Michael Caine as Scrooge, who wisely plays the part as straight as possible despite having a puppet show (quite literally) going on about him. Most of the supporting characters are played by Muppets, including Kermit as Bob Cratchit, Miss Piggy as Mrs. Cratchit, Fozzy as Mr. Fozziwig, and Statler and Waldorf as “the Marley brothers.” One of the true highlights of the Muppets’ canon, though it sadly represented something of a “last gasp” for the Henson Company’s singular creations, who would begin a slow descent into obscurity throughout the 1990s before making something of a comeback with 2011’s The Muppets.

Scrooge Trivia: The Muppet Christmas Carol was also notable for being the first Muppets movie to be produced and released after the death of creator Jim Henson in 1989; appropriately, it was directed by his son, Brian.

A Christmas Carol (1999)

While hardly the worst version of A Christmas Carol out there, this one may be the most disappointing. Produced for the cable channel TNT, this adaptation was meticulously faithful to the Dickens novella, including maintaining much of its original language and using music and trappings that would be authentic to 1843 England. Patrick Stewart starred as Scrooge, following a series of successful stage performances of the story on both Broadway and the London stage (the latter of which saw him win an Olivier Award), and, though it pains me to say it, he does a surprisingly forgettable job. The entire production, unfortunately, is generally flat, unimaginative, listless, and even, at times, mechanical, with very little of the story’s emotion or message remaining here intact.

Scrooge Trivia: It’s possible that a big part of this film’s problem was that Stewart only played Scrooge; in his award-winning one-man stage interpretation (which he adapted himself), Stewart actually played all of the roles himself – including Tiny Tim!

A Christmas Carol: The Musical (2004)

A made-for-TV adaptation of the Alan Menken/Lynn Ahrens musical, this version made very little effort to hide its relative staginess. Kelsey Grammar starred as a somewhat less-than-convincing Scrooge, with Jason Alexander as Marley, Jane Krakowski as the Ghost of Christmas Past, Geraldine Chaplin as the Ghost of Christmas Yet-to-Come, Jesse L. Martin as the Ghost of Christmas Present, and Jennifer Love Hewitt as the lost love of Scrooge’s youth. To be fair to Grammar and the rest of the cast, this version wasn’t exactly aiming for realism, so one’s enjoyment of it is really mostly dependent on whether you like the music and can overall abide the cheesy wigs and obvious sets. Personally, I’ve always found most of the songs to be pretty forgettable (I first saw the musical in the late 90s at Radio City Music Hall, with Roger Daltrey in the lead role), but the story’s still there and the cast is nonetheless likeable enough; it’s hardly anything anyone would call “must-see,” however.

Scrooge Trivia: One of the most interesting aspects of the musical are the significant liberties that it takes with Scrooge’s backstory, most of which was actually derived from the early life of author Charles Dickens; just as with the musical’s Scrooge, Dickens’s father was sent to debtors prison when he was only ten years old, and young Charles spent many of his formative years working for ten hours a day at a boot-blacking factory. While in the musical the cruelty of this childhood drives Scrooge to become a penny-pinching miser, in reality it drove Dickens to not only become a tireless, prolific author and the greatest novelist of his age, but a staunch social critic, outspoken proponent of child welfare, and a far-reaching philanthropist to the poor and downtrodden.

A Christmas Carol (2009)

This recent big budget, high-gloss adaptation, produced by Disney and directed by Robert Zemeckis using 3D motion capture animation (he also penned the script) was something of a box office and critical disappointment when it was released a few years ago, though there’s actually a fair bit to like here. Starring Jim Carrey as not only Scrooge but all three Ghosts of Christmas (an idea which comes off better than one might think), and co-starring Gary Oldman, Robin Wright Penn, Cary Elwes, and Colin Firth in a variety of supporting roles, this film had its heart in the right place. The problem was that the most of the CGI-heavy action sequences were overdone well past the point of effectiveness and too often got in the way of the story and the performances. It’s a shame, too, as the film does have some very, very effective scenes, and Carrey, all told, does an admirable job as Scrooge (though he was pretty much doing a dead-on Alistair Sim impression).

Scrooge Trivia: While the image and presentation of the Ghosts of Christmas Past and Future generally remain consistent throughout the many versions of A Christmas Carol, the Ghost of Christmas Past has often been far more open to interpretation. Dickens’s description of the apparition was largely ambiguous, even to its gender, meaning that it has, over time, been played by both men and women. In Zemeckis’s version, he presented Dickens’s metaphorical comparison of the Ghost’s visage to a candle’s flame quite literally, depicting it as a living candle with a flame for its head.

Doctor Who – “A Christmas Carol” (2010)

Presented as the 2010 edition of the Doctor Who Christmas Special, this unique spin on Dickens story may be one of the most creative interpretations of it that I’ve seen. Written by series show-runner Stephen Moffat, this has the time-traveling alien do-gooder (Matt Smith) racing against time to save a ship (containing his companions the Ponds) from crashing into a human colony sometime in the distant future; naturally, the only person who can save them is a heartless, embittered old tyrant very reminiscent of Scrooge (played by a terrific Michael Gambon) who is all-too-willing to let them all die. Taking his cue from Dickens, the Doctor sets off to help him see the error of his ways, which he does by using the TARDIS to go back in time and rewrite the old man’s unhappy life (!). Funny, touching, romantic, and, as is typical of the series, very, very clever, this stands as not only the best of the Who Christmas specials, but also serves as a really excellent primer for novices to the Doctor Who Universe (or Whoniverse, if you will).

Scrooge Trivia: One of the most prominent themes in A Christmas Carol that often goes understated (but which was prominent in this Doctor Who version), is that of lost love, as Scrooge’s shattered courtship as a young man was a leading cause of both his bitterness and his resentment of his nephew Fred’s happy marriage. This may have been because Dickens himself had a contentious romantic life; his first love was sent away to school in Paris when her parents found Dickens, then an impoverished young man of twenty, to be an unsuitable match for her. Later, he rather infamously left his wife Catherine, with whom he had ten children over twenty years of marriage, for actress Ellen Ternan, who at age 18 was 27 years Dickens’s junior.

Conclusion

“This boy is Ignorance and this girl is Want. Beware them both, and all of their degree, but most of all beware this boy…for on his brow I see that written which is Doom, unless the writing be erased.”

Sadly, if there’s an ancillary reason why A Christmas Carol has endured in popularity for most of the last 170 years, it’s because many of the social ills and hypocrisies that it tried to address are still all too prevalent. Especially in these recent economic hard times, too often we’ve all seen those who have more cast a dismissive eye to those who have less, and for many it remains a matter of ideological pride to judge their lack as a result of personal flaw or ingrained inferiority, as opposed to the harsh lot of circumstance. Though the recent election cycle is thankfully behind us, there were too many times where it often became painful to watch one of our Presidential candidates continuously bemoan and demean others for what they didn’t have, and dismiss their needs as not worthy of his time. Truly, every time I heard Mitt Romney, former venture capitalist, chastise the “47 percent,” or joke with the long unemployed about how he was “also looking for a job,” or encourage undocumented workers to self-deport, or claim that those unable to afford insurance could call an ambulance or visit an emergency room when they needed health care…I thought back to Ebenezer Scrooge in A Christmas Carol, asking the two men of charity, with cruel insincerity, “Are there no prisons? Are there no workhouses?”

Of course, it’s also in dark times where we see the goodness in people that Dickens championed, such as with the recent destruction wrecked by Superstorm Sandy and how it caused so many to not only open their wallets but also give of their time to help others. It shouldn’t take those times to force us to help one another, or to encourage us to think beyond our own sphere, but for all the crass commercialization that sometimes sours them, it’s good to know that we have our Holidays, whether they be Christmas, Hanukah, Ramadan, Kwanzaa, or what have you, to remind us that no one in this world should ever truly be on their own.

“And so, as Tiny Tim observed, God Bless Us, Every One!”