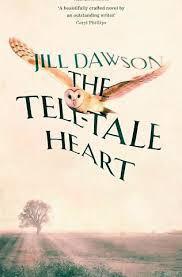

It just so happened that both Annabel and I had copies of Jill Dawson’s new novel, The Tell-Tale Heart, and by swiftness of reading and writing, Annabel’s was the review that made it into Shiny New Books. I’ve been saving up mine for the blog, though, as we both agreed it was one of the best books we read in the run-up to the magazine launch, and that Jill Dawson is an author who doesn’t get as much recognition as she deserves.

The Tell-Tale Heart is essentially the story of Patrick Robson, a 50-year-old professor of American Studies, ‘with one ex-wife and one ex-mistress and one daughter and one son I hardly ever see and one crappy job I no longer want and a case hanging over me and, God knows, nothing much to show for myself.’ He’s also been suffering from an advanced case of cardiomyopathy and given only six months to live. The story begins as he regains consciousness in his bed at Papworth Hospital outside Cambridge, only the third patient to have undergone the revolutionary ‘beating heart’ surgery, in which the heart is kept artificially pumping as opposed to preserved in ice, a technique which supposedly improves the chance of a successful transplant. Marooned in his bed for the lengthy process of recovery, Patrick has plenty of time to reflect on his past, and to consider the changes he feels strangely compelled to make to the extended future that now remains to him.

The Tell-Tale Heart is essentially the story of Patrick Robson, a 50-year-old professor of American Studies, ‘with one ex-wife and one ex-mistress and one daughter and one son I hardly ever see and one crappy job I no longer want and a case hanging over me and, God knows, nothing much to show for myself.’ He’s also been suffering from an advanced case of cardiomyopathy and given only six months to live. The story begins as he regains consciousness in his bed at Papworth Hospital outside Cambridge, only the third patient to have undergone the revolutionary ‘beating heart’ surgery, in which the heart is kept artificially pumping as opposed to preserved in ice, a technique which supposedly improves the chance of a successful transplant. Marooned in his bed for the lengthy process of recovery, Patrick has plenty of time to reflect on his past, and to consider the changes he feels strangely compelled to make to the extended future that now remains to him.

In this he is ambivalently aided by Maureen, his somewhat scatty but well-meaning transplant co-ordinator. Maureen is pushing him to write to the donor family, and horrifying him with the example letter she shows him, that Patrick considers full of saccharine ‘Hallmark’ sentiment. As he begins to compose a draft in his mind, however, the best he can come up with is:

Dear Donor Family. I am finding it very difficult to know what to say to you. A terrible truth: your good son’s heart is probably wasted on a man like me.’

It’s certainly the case that in his thoughtless womanising, his selfish pursuit of lust with no concern for the havoc he wreaked, as well as in his advanced illness, Patrick’s old heart has been every possible kind of unhealthy. But in his post-operative state, he begins to find the stirrings of entirely new feelings, a surprising perspective opens up to him on his ex-wife and daughter, a tenderness for their loyalty. He also feels himself growing fonder of Maureen, though whether this is a resurgence of his old tail-chasing ways or of a new fledgling relationship he cannot tell. He’s also surprisingly thrilled at the thought of giving up his job (he’s already under a cloud because of a pending sexual harrassment charge) and trying something different. Maureen is keen to read these changes in the light of cellular memory, the transplant of not just the heart, but the characteristics and tendencies of its previous owner, something Patrick dismisses with scorn. But then after a local newpaper article reveals too much about his donor, Patrick finds himself thinking more and more about the boy, Drew Beamish, whose motorbike crash led to his chance at a second life.

The narrative opens up to a second strand, which we might describe as tracing the blood line of Patrick’s new heart through Drew Beamish’s ancestors. The time is 1816, on the eve of the Littleport riots, provoked by the awful disparity between the poor folk of the Fens and the few wealthy landowners. Willie Beamiss is a young lad who is ‘in the suds about Politics’ with a father who ‘had a talent for whipping up others, and when labor is back-breaking and stomachs growl empty you can rile the sleepiest and loyalist of farm labourers to sedition.’ Willie’s life is subject to two great forces – the growing insurrection of his folk and a newfound passion for local beauty, Susie Spencer. As their love develops and unfurls, so the harsher, darker passions of the labourers rise up in company with it, and after a night of violence and looting, Willie finds himself thrust in jail along with nineteen others, his father among them, all fearing for their lives.

The beauty of The Tell-Tale Heart is that nothing is thrust upon the reader. We might interpret the passionate history of the Beamish’s – with its resting point in young Drew’s doomed infatuation for his school teacher – as a good match for Patrick. The refusal to blindly submit to the rules becomes a point of similarity, but whereas Patrick has coupled his with laziness and indifference to the feelings of others, the Beamish heart has loved openly and fiercely, seeking justice, self-advancement, love for its own sake. Patrick remains dismissive of ghostly echoes, but is compelled to seek out his donor’s mother, and be warned, the scene between them will break your heart, unless it’s made of stone. It’s a tribute to the easy flexibility of Jill Dawson’s narrative, that the novel can encompass both comedy and tragedy, the 19th century and the present day, and technology so futuristic that it brings with it a trace of ancient superstition. The uncanny properties of the human heart tie everything together in a story that beats with the enduring power of love in many forms. Just wonderful.

On a different note, I just wanted to alert you to a new page in the menu bar – I’ve brought together all the posts I’ve written over the years on literary and cultural theorists and their theories in a Gallery of Theorists. I’ll be doing the same thing shortly for my chronic fatigue posts, too.