American Art's Jo Ann Gillula speaks with Artistic Director Christopher Kendall about the upcoming season of the musical group in residence at the museum, 21st Century Consort, which opens their season with Aviary on October 25 in the museum's McEvoy Auditorium from 5 p.m to 8 p.m.

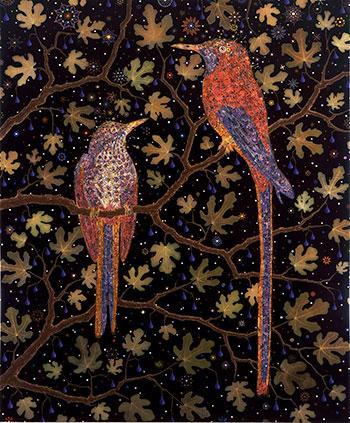

Fred Tomaselli, Migrant Fruit Thugs, 2006, leaves, photo collage, gouache, acrylic and resin on wood panel, Glenstone. © Fred Tomaselli. Image courtesy Glenstone

Eye Level: Is it really the 39th season of the consort? What was the very first concert and where was it held? Are you planning a special celebration next fall for the 40th anniversary?

Christopher Kendall: True confession: I can never quite figure out when you celebrate anniversaries (ask my wife). If this is our 39th season (it is), should we be celebrating this year or next? We decided on next, and are making some exciting plans (more on that at some later point). In any case, at our age, the Consort can justifiably celebrate every year: there aren't many new music or chamber groups who have survived so long. We credit our residency at the Smithsonian to a large degree for this; our home at American Art has been a terrific tonic, its exhibitions and collection an inspiration, and you and your staff the ideal partners in crime! One of the joys —and a poignancy too— of our residency here is that our very first concert 39 years ago took place in the Lincoln Gallery in this very building (then the National Collection of Fine Arts, right?)!

EL: Christopher, you have a most unusual repertoire lined up for the first concert, even for you who programs such varied contemporary music for the group. Are you actually combining 14th century and 21st century music? And as this concert celebrates our contemporary art exhibition, The Singing and the Silence: Birds in Contemporary Art, how do the two "blackbird" pieces differ?

CK: Perhaps the most unusual thing about this program is that most of it is downright un-American. Wait! I mean, not written by American composers, as a large percentage of our programs are (they are, after all, frequently related to the American art at the museum). But it happens there is an especially rich trove of European music having to do with birds, apropos this bird exhibition, running all the way back to the middle ages. Our arrangements, by Adam Har-zvi, of music of the 14th century follows a distinguished tradition by composers such as Harrison Birtwistle, Peter Maxwell Davies, Charles Wuorinen and others, who are clearly fascinated by the complexity and, to our modern ears, strangeness of this music. It may not be easy, in fact, for audiences at the concert to tell that these pieces were written so many centuries ago. I'm looking forward to experiencing these medieval French pieces in juxtaposition to music by the most bird-song-obsessed composer of our (and all) time, Olivier Messiaen. To answer your question: the blackbird and other ornithologically-inspired pieces are all quite different, but all are for the birds (in the very best sense!). And stay tuned for a special, thematically appropriate encore....

EL: We have gotten such acclaim for the now "annual" Christmas concert, featuring William Sharp as Ebeneezer Scrooge. Why do you think audiences respond so positively to this piece?

CK: We're grateful that our audiences' tastes align so well with ours, since we now appear to have to play this piece (The Passion of Scrooge or A Christmas Carol) year in and year out! But performing it is sheer pleasure, perhaps for some of the same reasons people want to hear (and see) it. It is music that truly appeals to head and heart. Compressing the entire Dickens novella into about an hour, basically squeezing out a lot of the text and replacing it with notes, means the composer Jon Deak has achieved an intense and engrossing experience, to perform and to witness. If anything, the loss of text and gain of notes makes this beloved story all the more touching and funny, scary and ultimately, uplifting. I'm moved to tears every year! And there is William Sharp's inimitable depiction of Scrooge (and most of the other characters in the story). We say Bill is Ebenezer when he's on that stage. The characters he is not playing are all represented by the instrumentalists, who literally deliver their lines as part of the music. It's all endlessly challenging for us, and a blessing for us, every one!

EL: I know you gave us a teaser last year from O Brien's Algebra of Night. Why did you particularly want to perform the piece in its entirety? And how do the other two pieces also speak to cityscapes of New York?

CK: This is an extraordinary composition by a composer for whom I have a special sympathy (we are both administrators, he at Indiana University and I at University of Michigan). We both endeavor to keep our artistic production going while contending with academia. Frankly, I had worked as a dean with Gene for years, dimly aware he was a composer but without actually hearing his work. When I encountered Algebra of Night, I was stunned. Here is a masterful and incredibly beautiful work, intellectually deep, via some magnificent poetry, and intensely lyrical, via the poems' settings for mezzo-soprano and a quartet of piano and strings. I have been eager to premiere the entire work, a long and ambitious cycle, and, following our performance, to record it. That's the plan. And in the preview of a few of the movements last year and now in the entire cycle, it's been a pleasure to introduce the wonderful mezzo Deanne Meek to the Consort and our audience. And to add, I'm also partial to the other, "night in the city" works we'll do on this February program. And watch out for another of those surprise encores.

EL: The museum opens an exhibition on The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi next spring, a Japanese artist who painted in a modernist fashion in America. How did you select the various works to represent the immigrant experience?

CK: I appreciate the way you phrased this question, since the big challenge here was one of selection. American music has been endlessly enriched, even defined, by immigrant composers, initially from Europe and by now from all over the world. So as a theme for a program, it is really way too broad. But we're focusing on Asian composers in recognition of the remarkable artist Yasuo Kuniyoshi, with a few other works by immigrant composers with special meaning to the Consort. So, unusually for us, we begin and end the season this year with works not by American composers. But in a way, all these distinctions break down, as American music increasingly embraces and is transformed by international influences and becomes a truly global language.

The Concert's program, Aviary takes place in American Art's McEvoy Auditorium, beginning at 5 p.m. There is a pre-concert discussion at 4 p.m. Admission is free.