Sign up for CNN's Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news about fascinating discoveries, scientific developments and more.

For nearly two centuries, scientists have tried to solve an enduring mystery about a giant centipede-like animal called Arthropleura, which used its many legs to roam the Earth more than 300 million years ago.

Now two well-preserved fossils of the creature, unearthed in France, have finally revealed what Arthropleura's head looked like, providing insight into how the giant arthropod lived.

Today, arthropods are a group that includes insects, crustaceans, arachnids such as spiders and their relatives - and the extinct Arthropleura is still the largest known arthropod to ever live on Earth.

Scientists in Britain first found fossils of Arthropleura in 1854, with some adults reaching 2.6 meters in length. But none of the fossils contained a head, which would help researchers determine key details about the creature, such as whether it was a predator similar to centipedes or an animal that merely fed on decaying organic matter like centipedes.

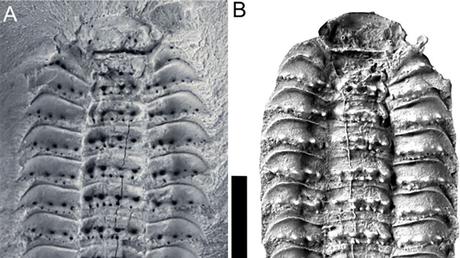

In a search for the first complete head, researchers conducted an analysis of Arthropleura fossils from two young individuals discovered in France in the 1970s. The findings were published October 9 in the journal Science Advances.

Arthropleura's strange story took a new twist when the research team scanned the fossils, which are still trapped in stone.

The head of each animal shows features of both millipedes and millipedes, indicating that the two types of arthropods are more closely related than previously thought, the study authors said.

"By combining in this study the best available data from hundreds of genes from living species, in addition to the physical characteristics that allow us to place fossils like Arthropleura on evolutionary trees, we have managed to square this circle. Centipedes and centipedes are actually each other's closest relatives," says co-author and paleontologist Dr. Greg Edgecombe, an expert on ancient invertebrates at London's Natural History Museum, said in a statement.

A time for giants

From the fossils and tread-like tracks left by Arthropleura, scientists have determined that the enormous insect lived between 290 million and 346 million years ago in what is now North America and Europe - and that it was just one of many giants that roamed the planet wandered.

An abundance of atmospheric oxygen allowed creatures such as scorpions and now-extinct dragonfly-like insects called griffins to reach enormous sizes that dwarf their modern counterparts, the study authors said. But Arthropleura still stood out, reaching about the same length as modern alligators, said lead study author Mickaël Lhéritier.

Lhéritier is pursuing her PhD at France's Claude Bernard University Lyon 1 in the field of ancient myriapods, a group of arthropods that include centipedes and millipedes, to understand how arthropods adapted to live on land millions of years ago.

Once the animals died and became buried in layers of sediment over time, some of them were buried in a mineral known as siderite, which solidified and formed a lump around the remains. Being encased in stone allowed for the preservation of even the most delicate aspects of the fossilized creatures.

Such nodules were first noticed in a coal mine in Montceau-les-Mines, France, in the 1970s and subsequently transferred to French museum collections.

"Traditionally, we split open the nodules and made casts of the specimens," Edgecombe said. "Nowadays we can examine them with scans. We used a combination of microCT (micro-computed tomography) and synchrotron imaging to examine the Arthropleura inside, revealing the fine details of its anatomy."

An intriguing arthropod ancestor

The 3D scans revealed two nearly complete specimens of Arthropleura that lived 300 million years ago. Both fossilized insects still had most of their legs, and one of them had a complete head, including antennae, eyes, mandibles and its feeding apparatus - the first Arthropleura head ever documented, Lhéritier said.

The team was surprised to find that Arthrorpleura had body features seen in modern millipedes, such as two pairs of legs per body segment, as well as the head features of early millipedes, such as the positioning of the mandibles and the shape of the feeding apparatus. The creature also had stalked eyes, like crustaceans, Lhéritier said.

The discovery not only helps researchers better understand what Arthropleura looked like, but also establishes a closer evolutionary connection between modern millipedes and centipedes.

Previously, scientists thought the two arthropods had a more distant relationship, but in recent years genetic studies have shown that centipedes and millipedes were more closely related.

"This new scenario was criticized for the fact that there was no 'fossil' or anatomical argument to defend this grouping, but our new findings on Arthropleura, which combine features of both groups, seem to confirm this new scenario," Lhéritier wrote in an article. e-mail.

Researchers believe the two Arthropleura fossils belonged to juvenile specimens because they are only 25 millimeters and 40 millimeters long.

Research on Arthropleura specimens has shown that the animals vary in the number of body segments they have, similar to most centipedes that add body segments until they reach a fixed maximum. But according to the study authors, centipedes have all their body segments in place at birth.

This finding suggests that Arthropleura reached peak segmentation as an adult, rather than at birth. But the researchers are curious whether they have found true juvenile specimens, or a previously unknown smaller species, as well as the growth rate over time for such an animal.

"Tracks found elsewhere in Montceau-les-Mines suggest that these Arthropleura were probably about 40 centimeters long at their longest," Edgecombe said. "While there's nothing to say they couldn't be bigger, we don't have any evidence of that at the moment."

What Arthropleura Ate and Other Mysteries

Now that researchers have uncovered a complete Arthropleura head, they hope the discovery can help them solve other riddles about the giant animal, including what it ate and how it breathed. But other fossils will have to be found that preserve additional aspects of the arthropod's body, including the head of an adult.

"Although the definitive gut contents have yet to be found, other details from these fossils add to the debate about Arthropleura's diet," Edgecombe said. "They don't have fangs or legs (specialized) for catching prey, which suggests they were probably not a predator. Because its legs are better suited for slow movements, they probably looked more like the garbage-eating centipedes alive today."

Lhéritier, who studies another group of ancient millipedes that may have been amphibious, said he is curious about Arthropleura's stalked eyes.

"Today, stalked eyes are a typical feature of aquatic arthropods such as crabs and shrimp," he said. 'Could this mean that Arthropleura could have been amphibious? To answer this, we need to find the respiratory system of Arthropleura. Finding these organs can help us understand Arthropleura's link with water. Gills like crustaceans would mean an aquatic/amphibian lifestyle, while tracheas (like insects or other centipedes) or lungs (like spiders) would mean a terrestrial lifestyle."

But unraveling what Arthropleura's head looks like will solve an important mystery, says James C. Lamsdell, an associate professor of geology at West Virginia University, in a related article appearing in Science Advances. Lamsdell was not involved in the new investigation.

"(These) remarkable findings, based on two nearly complete young individuals, provide a new perspective on this enigmatic arthropod," Lamsdell wrote.

"(T)he most exciting discovery comes from the heads of the specimens that bear a mosaic of centipede and millipede features. ... Now that the mystery of the affinities of the largest known arthropod has been put to rest, the work of reconstructing the life history of this extraordinary creature can finally begin."

For more CNN news and newsletters, create an account at CNN.com