(This article is part of a series, The Thinking Planet, exploring the universal nature of cognition in the living world. All concepts and examples are drawn from an analysis of my comprehensive work, “Silent Earth: Adaptations for Life in a Devastated Biosphere.”)

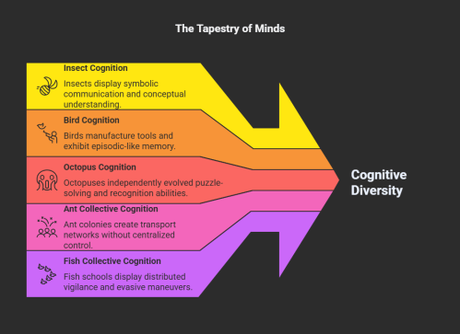

While plants and microbes show us that a brain isn’t required for cognition, the animal kingdom reveals an explosive diversity of minds shaped by evolution. Silent Earth details how different ecological challenges have produced a stunning array of cognitive solutions.

- Insects, with their tiny brains, accomplish remarkable feats. Honeybees communicate the location of resources through a symbolic dance language and even display a conceptual understanding of zero (Chittka and Niven 2009; Howard et al. 2018).

- Birds like the New Caledonian crow manufacture complex tools with features designed for specific tasks, a skill demonstrating causal understanding (Emery and Clayton 2004). Western scrub-jays exhibit episodic-like memory, remembering what food they hid, where, and when (Clayton and Dickinson 1999).

- Octopuses represent a fascinating case of convergent evolution. Separated from vertebrates by over 500 million years, they have independently evolved puzzle-solving abilities, tool use, and the capacity to recognize individual humans (Godfrey-Smith 2016; Hochner et al. 2006).

But cognition isn’t just an individual affair. Silent Earth highlights the power of collective cognition, where complex problem-solving emerges from the interaction of many individuals.

- Ant colonies act as a “superorganism,” creating efficient transport networks between the nest and food sources without any centralized control or leader (Deneubourg et al. 1990; Gordon 2010).

- Fish schools display distributed vigilance. An evasive maneuver by a few fish on the edge of the group can propagate rapidly through the entire school, allowing fish far from the initial detection to respond to a threat they haven’t personally seen (Couzin and Krause 2003; Rosenthal et al. 2015).

From the specialized mind of a tool-making crow to the emergent intelligence of an ant colony, the biosphere is a showcase of cognitive diversity. There is no single ladder of intelligence with humans at the top, but rather a rich tapestry of minds, each a unique solution to the challenge of living (Shettleworth 2010).

In the next post, I will explore why this “thinking planet” is so important and how the cognitive abilities of all these organisms contribute to a more stable and resilient world.

References

Chittka, L., and Niven, J. E. 2009. Are bigger brains better? Current Biology 19(21): R995-R1008.

Clayton, N. S., and Dickinson, A. 1999. Episodic-like memory in scrub jays. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 354(1387): 1481-1495.

Couzin, I. D., and Krause, J. 2003. Self-organization and collective behavior in vertebrates. Advances in the Study of Behavior 32: 1-75.

Deneubourg, J. L., et al. 1990. The blind leading the blind: Modeling chemically mediated army ant raid patterns. Journal of Insect Behavior 3(5): 719-725.

Emery, N. J., and Clayton, N. S. 2004. The mentality of crows: Convergent evolution of intelligence in corvids and apes. Science 306(5703): 1903-1907.

Godfrey-Smith, P. 2016. Other minds: The octopus, the sea, and the deep origins of consciousness. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, New York, 272 p.

Gordon, D. M. 2010. Ant encounters: Interaction networks and colony behavior. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 185 p.

Hochner, B., et al. 2006. The octopus: a model for a comparative analysis of the evolution of learning and memory mechanisms. The Biological Bulletin 210(3): 308-317.

Howard, S. R., et al. 2018. Numerical ordering of zero in honeybees. Science 360(6393): 1124-1126.

Rosenthal, S. B., et al. 2015. Revealing the unseen majority: ULV-based assessment of plankton reveals profound impacts of kleptoparasites on crustacean zooplankton. Limnology and Oceanography 60(5): 1591-1604.

Shettleworth, S. J. 2010. Cognition, evolution, and behavior. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 720 p.