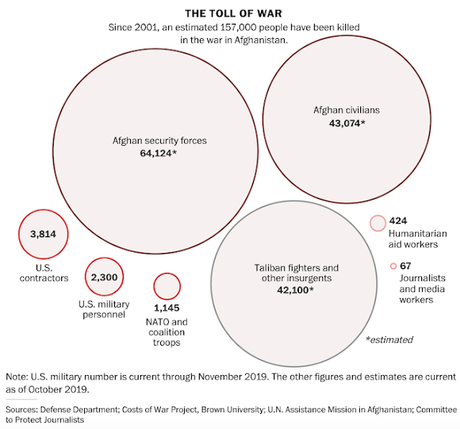

There have been more than 150,000 people killed in the war in Afghanistan, and the United States has spent more than a trillion dollars since the war started. Are we winning? Have we achieved any of our goals in Afghanistan?

If you answered yes, it's because we have been lied to by the last three administrations about that war. The sad truth is that beyond killing Osama bin Laden (which could have been done without the war), we have not accomplished any of our goals and are not likely to do so in the future. It is a war that cannot be won.

The Washington Post has published an excellent article about that war. They went to court and got their hands on more than 2,000 pages of official government documents. The documents were government interviews with American generals/soldiers, diplomats, aid workers, and Afghan officials. The interviews were conducted to see what was done wrong in the war and how it could be fixed.

What they discovered was that the war was a clusterfuck from the beginning, and just got worse from there. I highly recommend you read the entire article. Here is just a part of it:

The Lessons Learned interviews contain few revelations about military operations. But running throughout are torrents of criticism that refute the official narrative of the war, from its earliest days through the start of the Trump administration. At the outset, for instance, the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan had a clear, stated objective — to retaliate against al-Qaeda and prevent a repeat of the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. Yet the interviews show that as the war dragged on, the goals and mission kept changing and a lack of faith in the U.S. strategy took root inside the Pentagon, the White House and the State Department. Fundamental disagreements went unresolved. Some U.S. officials wanted to use the war to turn Afghanistan into a democracy. Others wanted to transform Afghan culture and elevate women’s rights. Still others wanted to reshape the regional balance of power among Pakistan, India, Iran and Russia. “With the AfPak strategy there was a present under the Christmas tree for everyone,” an unidentified U.S. official told government interviewers in 2015. “By the time you were finished you had so many priorities and aspirations it was like no strategy at all.” The Lessons Learned interviews also reveal how U.S. military commanders struggled to articulate who they were fighting, let alone why. Was al-Qaeda the enemy, or the Taliban? Was Pakistan a friend or an adversary? What about the Islamic State and the bewildering array of foreign jihadists, let alone the warlords on the CIA’s payroll? According to the documents, the U.S. government never settled on an answer. As a result, in the field, U.S. troops often couldn’t tell friend from foe. “They thought I was going to come to them with a map to show them where the good guys and bad guys live,” an unnamed former adviser to an Army Special Forces team told government interviewers in 2017. “It took several conversations for them to understand that I did not have that information in my hands. At first, they just kept asking: ‘But who are the bad guys, where are they?’ ” The view wasn’t any clearer from the Pentagon. “I have no visibility into who the bad guys are,” Rumsfeld complained in a Sept. 8, 2003, snowflake. “We are woefully deficient in human intelligence.” As commanders in chief, Bush, Obama and Trump all promised the public the same thing. They would avoid falling into the trap of "nation-building" in Afghanistan. On that score, the presidents failed miserably. The United States has allocated more than $133 billion to build up Afghanistan — more than it spent, adjusted for inflation, to revive the whole of Western Europe with the Marshall Plan after World War II. The Lessons Learned interviews show the grandiose nation-building project was marred from the start. U.S. officials tried to create — from scratch — a democratic government in Kabul modeled after their own in Washington. It was a foreign concept to the Afghans, who were accustomed to tribalism, monarchism, communism and Islamic law. “Our policy was to create a strong central government which was idiotic because Afghanistan does not have a history of a strong central government,” an unidentified former State Department official told government interviewers in 2015. “The timeframe for creating a strong central government is 100 years, which we didn’t have.” Meanwhile, the United States flooded the fragile country with far more aid than it could possibly absorb. During the peak of the fighting, from 2009 to 2012, U.S. lawmakers and military commanders believed the more they spent on schools, bridges, canals and other civil-works projects, the faster security would improve. Aid workers told government interviewers it was a colossal misjudgment, akin to pumping kerosene on a dying campfire just to keep the flame alive. One unnamed executive with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), guessed that 90 percent of what they spent was overkill: “We lost objectivity. We were given money, told to spend it and we did, without reason.” Many aid workers blamed Congress for what they saw as a mindless rush to spend. One unidentified contractor told government interviewers he was expected to dole out $3 million daily for projects in a single Afghan district roughly the size of a U.S. county. He once asked a visiting congressman whether the lawmaker could responsibly spend that kind of money back home: “He said hell no. ‘Well, sir, that’s what you just obligated us to spend and I’m doing it for communities that live in mud huts with no windows.’ ” The gusher of aid that Washington spent on Afghanistan also gave rise to historic levels of corruption. In public, U.S. officials insisted they had no tolerance for graft. But in the Lessons Learned interviews, they admitted the U.S. government looked the other way while Afghan power brokers — allies of Washington — plundered with impunity. Christopher Kolenda, an Army colonel who deployed to Afghanistan several times and advised three U.S. generals in charge of the war, said that the Afghan government led by President Hamid Karzai had “self-organized into a kleptocracy” by 2006 — and that U.S. officials failed to recognize the lethal threat it posed to their strategy. “I like to use a cancer analogy,” Kolenda told government interviewers. “Petty corruption is like skin cancer; there are ways to deal with it and you’ll probably be just fine. Corruption within the ministries, higher level, is like colon cancer; it’s worse, but if you catch it in time, you’re probably ok. Kleptocracy, however, is like brain cancer; it’s fatal.” By allowing corruption to fester, U.S. officials told interviewers, they helped destroy the popular legitimacy of the wobbly Afghan government they were fighting to prop up. With judges and police chiefs and bureaucrats extorting bribes, many Afghans soured on democracy and turned to the Taliban to enforce order. “Our biggest single project, sadly and inadvertently, of course, may have been the development of mass corruption,” Crocker, who served as the top U.S. diplomat in Kabul in 2002 and again from 2011 to 2012, told government interviewers. He added, “Once it gets to the level I saw, when I was out there, it’s somewhere between unbelievably hard and outright impossible to fix it.” Year after year, U.S. generals have said in public they are making steady progress on the central plank of their strategy: to train a robust Afghan army and national police force that can defend the country without foreign help. In the Lessons Learned interviews, however, U.S. military trainers described the Afghan security forces as incompetent, unmotivated and rife with deserters. They also accused Afghan commanders of pocketing salaries — paid by U.S. taxpayers — for tens of thousands of “ghost soldiers.” None expressed confidence that the Afghan army and police could ever fend off, much less defeat, the Taliban on their own. More than 60,000 members of Afghan security forces have been killed, a casualty rate that U.S. commanders have called unsustainable. One unidentified U.S. soldier said Special Forces teams “hated” the Afghan police whom they trained and worked with, calling them “awful — the bottom of the barrel in the country that is already at the bottom of the barrel.” A U.S. military officer estimated that one-third of police recruits were “drug addicts or Taliban.” Yet another called them “stealing fools”who looted so much fuel from U.S. bases that they perpetually smelled of gasoline. “Thinking we could build the military that fast and that well was insane,” an unnamed senior USAID official told government interviewers. Meanwhile, as U.S. hopes for the Afghan security forces failed to materialize, Afghanistan became the world’s leading source of a growing scourge: opium. The United States has spent about $9 billion to fight the problem over the past 18 years, but Afghan farmers are cultivating more opium poppies than ever. Last year, Afghanistan was responsible for 82 percent of global opium production, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.