The opening moments of Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket, which play over Johnny Wright’s ballad “Hello Vietnam”, feature his central characters on their first day of basic training. They have joined - or were drafted into - the United States Marine Corps. Most, if not all of them, will be heading to Vietnam once their training is over. Yet the first thing they experience, on that very first day on Parris Island, is a barber’s chair. Every incoming recruit has their head shaved.

I have always heard this particular ritual was symbolic, a way to put each and every man, regardless of race or background, on an even playing field. They are no longer individuals, and before long they won’t even have a name anymore. Just a nickname, assigned to them by their bombastic drill instructor, Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, played to perfection by R. Lee Ermey (in part because, as a former Marine drill instructor in real life, he was essentially playing himself).

Among the raw recruits Hartman must mold into finely-tuned soldiers are Joker (Matthew Modine), Cowboy (Arliss Howard), Snowball (Peter Edmund), and the dim-witted Private Pyle (Vincent D’Onofrio, in what is undoubtedly one of the greatest screen debuts in cinematic history).

Hartman is merciless in his approach to their training, especially where Pvt. Pyle is concerned. Overweight and a little slow, Hartman works on Pyle, insulting him at every turn, and humiliating him when he cannot complete the obstacle course. When Pyle continues to foul up, Hartman changes tactics by punishing the entire platoon. If he cannot motivate Pyle, then maybe incurring the wrath of his fellow recruits will do the trick (in one of the film’s most disturbing scenes, the squad does take its anger out on Pyle after lights out).

Pyle eventually falls into place, and becomes like everyone else. But his psyche has been shattered. Hartman’s goal at the outset was to break every man down and build them up again, into a team, proud members of the United States Marine Corps. The tale of Pvt. Pyle is what happens when a broken man cannot be rebuilt, and his story stands as the first act of Kubrick’s masterwork, a film as much about the mentality of war as it is about war itself.

Now that the recruits have been prepared for life in the Marine Corps, it is off to war. Most are assigned to infantry units in Vietnam, but Pvt. Joker, who occasionally acts as the film’s narrator, fancies himself a writer, and joins the staff of Stars and Stripes. He is assigned a photographer, Rafterman (Kevyn Major Howard), and writes stories that reflect favorably on the U.S. war effort.

That changes, however, after the Tet Offensive, when the Viet Cong breaks a peace treaty during the country’s New Years’ festivities and hands the Americans a handful of crippling defeats. With things looking bleak for the U.S., Joker and Rafterman are re-assigned to field duty, to tag along with a platoon of Marine grunts and report on their progress.

By chance, Joker is sent to the unit of his old buddy Cowboy, who, along with fellow Marines Eightball (Dorian Harewood), Animal Mother (Adam Baldwin), and Lt. Touchdown (Ed O’Ross), are sent to a deserted village to verify reports that the enemy has retreated, only to find themselves facing off against a very skilled sniper.

So, that’s the story that makes up Full Metal Jacket, but it doesn’t scratch the surface of what Kubrick and his team accomplish with this movie.

The second half of the film, which centers on the war itself, is skillfully shot, with fluid handheld shots that follow the Marines as they carry out their orders, moving from one life-threatening situation to the next. These scenes are punctuated by the film’s haunting score (created by Vivian Kubrick, under the alias Abigail Mead), which keeps the audience on edge, always at the ready for something to happen.

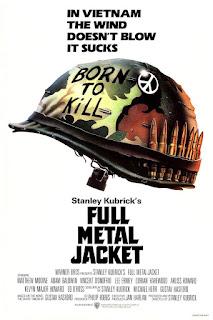

The cast is equally superb, with Matthew Modine leading the way as the complex Joker; he wears a peace symbol on his uniform, but has “Born to Kill” written on his helmet. Because we spend more time with him than any other character, Modine's Joker is essentially the lead. But every individual gets a moment in the sun, and is given a chance to strut their stuff. And they all make the most of the opportunity (especially D’Onofrio and Adam Baldwin, who more than earns his character's nickname "Animal Mother").

The sets are well-realized, the action scenes are impeccably staged, and the inherent drama of the basic training sequences builds the tension to an almost unbearable level.

But then, when it comes to Kubrick, we know the physical aspects of a film will be flawless. He was a perfectionist, doing as many as 30-40 takes of a scene, until he, and his cast and crew, got it right. To call Full Metal Jacket a stunning technical achievement is not newsworthy. Kubrick would have never released it were it not so.

What it comes down to, then, is the film’s central theme, and how Kubrick and his team convey it: the effect of not only war, but the preparation for war on the individual, as seen through the eyes of men whose individuality has been stripped away. Kubrick could have easily made some grand statement here, damning the loss of one’s identity, or the impact that uncertain death can have on a man’s psyche. There are traces of both here, but more than anything, it is about the attitude of the soldier, who knows he could die at any minute yet performs his duties without question.

There is no cowardice to be found in Full Metal Jacket, no hesitation in carrying out orders, regardless of how dangerous they might be, or their ultimate consequences. Kubrick’s fascination, as I see it, was with the mindset of soldiers in the midst of war, who, surrounded by enemy combatants attempting to kill them, somehow throws caution to the wind to serve their country. Gunnery Sergeant Hartman’s job was to turn men into killing machines, and Kubrick shows us time and again during the Vietnam sequences that he and his fellow drill instructors managed to do exactly that.

I saw Full Metal Jacket during its initial run in 1987 with my father, who is himself a Vietnam veteran. He had been critical of some Vietnam-themed films in the past, saying he found Apocalypse Now “weird”, and Platoon a little too over-the-top. During the initial scenes of Full Metal jacket, I sat there and wondered what his reaction to this movie was going to be.

As the story played out, though, I realized that Kubrick had pulled me into his film completely, to the point that, when the end credits did finally roll, my father’s opinion was no longer my primary concern. I knew I had just seen a masterpiece, and that was all that mattered.

Rating: 10 out of 10