A blood-stained “do not disturb” sign hung on the door of hotel room 1215 of the Dupont Plaza in down-town Miami. Inside, the bodies of Chinese-Jamaican father and son Derrick Moo Young, 53, and his son Duane, 23, lay on the floor.

A blood-stained “do not disturb” sign hung on the door of hotel room 1215 of the Dupont Plaza in down-town Miami. Inside, the bodies of Chinese-Jamaican father and son Derrick Moo Young, 53, and his son Duane, 23, lay on the floor.

Downstairs a journalist, Neville Butler, was seen walking through the lobby with blood-splattered on his clothes and shoes, his shirt ripped open and a broken watch.

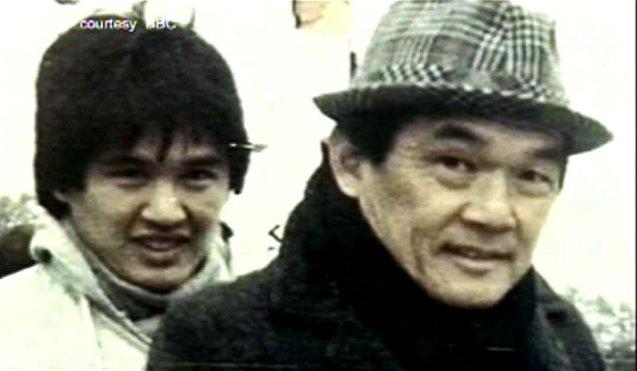

Earlier that morning Krishna Maharaj (pictured above) had entered room 1215 for a business meeting set up by Mr Butler. His fingerprints were on a coffee cup and newspaper.

A Columbian man in the room opposite 1215 checked out, with the Moo Youngs’ blood on his door too. That same morning a man, thought to be Adam Amer Hosein, who bore an uncanny resemblance to Mr Maharaj, was also seen in the hotel, according to a witness.

The victims: Derrick and Duane Moo Young

Another man, Eddie Dames, told a colleague he was going to the hotel that morning too, and was later seen in a car with a blood-splattered Mr Butler.

Nobody had heard anything. The fatal shootings may well have been carried out with a silencer. Mr Butler went to the police and reported that he had seen Mr Maharaj carry out the double-killing and that he had been forced to take part.

These events took place on October 16th 1986. According to the State the murders took place sometime between 11am and noon. Mr Maharaj was convicted of the killings and sentenced to death.

Over 25 years later the case remains mired in controversy. Six witnesses place Mr Maharaj in Fort Lauderdale at the time the prosecution say the murder was committed and gave statements but none were called to give evidence.

Mr Butler was granted immunity from prosecution to testify against Mr Maharaj, who has now spent a quarter of a century behind bars. 15 of those were on death row after being handed the death penalty.

The death penalty was quashed in 2002 but the Florida authorities refused to free Mr Maharaj who was instead handed a 50 year jail term and faces dying behind bars for a crime he, and many others, say he did not commit.

He has always freely admitted being inside the hotel room but denies having anything to do with the murders and claims he was set-up to be the fall-guy because he had a business dispute with the Moo Youngs. Lured to the scene on false pretences, he maintains he is a victim of a conspiracy to pin blame for a professional hit on him while other theories about possible motives for the homicide were ignored.

Witness: Neville Butler

Beside the Moo Youngs’ bodies, a briefcase belonging to the Moo Youngs’ which was never revealed during the original trial in 1987. It contained evidence of possible illegal activities of the victims that would have provided a strong motive for someone else to kill them.

Papers, some signed by the Moo Youngs’, suggested their companies had given loans of up to US$1.5 billion each to several Caribbean governments. One document referred to a financial transfer involving a staggering US$5 billion in Japanese Yen bonds.

Receipts also revealed evidence of a lavish multi-millionaire lifestyle seriously at odds with their annual tax returns in the United States which suggested that the Moo Youngs’ lived on the breadline with a total household income of just US$20,000 a year earned through a modest bathroom fittings business. That would have meant the Moo Youngs living in relative poverty, yet they traveled the world staying at expensive hotels and ate at the best restaurants.

The accountancy firm Ernst and Young have carried out analysis of the contents of the briefcase, which were not disclosed at the trial. They conclude that the Moo Youngs could not have been operating a legitimate business and were either dealing in drugs or laundering money. According to Mr Maharaj’s current lawyer, Clive Stafford Smith, the briefcase papers showed the Moo Youngs’ were big time “money-launderers.”

According to the State, the murders took place between 11am and noon. Mr Maharaj says he arrived at the hotel at around 8.30am and when his business contact, Mr Dames, failed to arrive he left at 10.20am before driving 30 miles away to Fort Lauderdale.

Questioned by police, Mr Dames claimed he was shopping with a friend, Prince Ellis, at the time of the double-killing. But Mr Ellis has since recanted his testimony and claimed that Mr Dames was involved in the crime.

Questioned by police, Mr Dames claimed he was shopping with a friend, Prince Ellis, at the time of the double-killing but Mr Ellis later recanted his testimony and claimed that Mr Dames was involved in the crime.

Various witnesses collaborate Mr Maharaj’s story that he visited a printing press in Fort Lauderdale at the time the murders were said to have taken place, before having lunch with Portuguese-born wife Marita, at 1pm,when police swooped. Yet none of the witnesses backing Mr Maharaj were called to give evidence.

Apart from one. When first interviewed Tino Geddes confirmed Mr Maharaj’s story that they were together at the printing press. But later he changed his version of events and testified against him. Mr Geddes’s testimony was crucial to the conviction.

Astonishingly, during the 1987 trial a stunned jury watched in amazement as the trial judge, Howard Gross, was led away in handcuffs, and later disbarred, following an FBI sting into a number of corrupt judges in Dade County, Florida.

Mr Maharaj says the same judge tried to solicit a bribe from him through intermediaries, but his original defence team failed to complain or call for a retrial. Just as bizarrely, the new judge, Harold Solomon, asked the prosecutors to write the order sentencing Mr Maharaj to death before the sentencing hearing had even begun.

A policeman who was part of the team investigating the murders, Ron Petrillo, told BBC Newsnight that there was “no doubt” in his mind that Mr Maharaj was innocent. He said he was “stunned” that defence witnesses were not called. Mr Petrillo also said that a lawyer defending Mr Maharaj told him he had received a threatening phone call, a claim the lawyer now denies.

The only man to have admitted being inside room 1215 when the murders were committed, Mr Butler, was receiving “help” from the State over a drink-drive offense when he gave evidence, according to Mr Maharaj’s current lawyers from the anti-death penalty campaign group Reprieve.

Mr Butler was a reporter on the Caribbean Echo which was run by a man named Eslee Carberry. Mr Maharaj knew Mr Carberry because they were both newspaper proprietors on the islands. Mr Maharaj owned the rival Caribbean Times but the two publishers were on speaking terms.

When, in 1986, Mr Maharaj believed he had been defrauded by the Moo Youngs’ to the tune of US$400,000 he approached Mr Carberry to run a story about it in the Echo and paid Mr Carberry a $400 “sponsorship fee” for the article.

Derrick Moo Young was angered by this and went to Mr Carberry himself. The Caribbean Echo then published a series of articles attacking Mr Maharaj and accusing him of taking millions of dollars out of Trinidad. Mr Maharaj called in the lawyers with a view to suing the Moo Youngs’ for monies he felt was owed to him, and was advised he had a strong case. Mr Maharaj claims he had no idea that the Moo Youngs were at the DuPont Plaza that day and had no reason to meet them.

Mr Butler told the Miami court that as the Moo Youngs entered the room Mr Maharaj emerged carrying a pillow in his left hand and a gun in his gloved right hand before ordering Mr Butler to tie up the victims before Mr Maharaj shot them. No gun has ever been found but the bullets could have come from a Smith and Wesson 39 like the one Mr Maharaj owned.

However ballistics reports suggest that two different types of bullets were used suggesting a second gun may have been in play.

However there was no ballistic evidence which proved that Mr Maharaj had fired his Smith and Wesson at all, let alone in the hotel. No residue, such as blood or gun powder, was on Mr Maharaj. And he had no scratches or injuries, in stark contrast to the appearance of Mr Butler when he left the hotel. However no evidence has emerged to suggest that Mr Butler fired a gun.

Garage mechanic George Abchal has another theory. He told a BBC Newsnight investigation in 2004 that his boss, Mr Hosein, owned a gun and silencer and told him he was going to the hotel that day.

Mr Abchal also claims that Mr Hosein told him he had “eliminated” a two people whom he had owed money to, been paid $200,000 and gained possession of some cocaine. Yet Mr Abchal was never called to give evidence. Yet police never interviewed Mr Hosein or considered him material to the case.

Court documents show that Mr Hosein and Mr Dames have been linked to F. Nigel Bowe, a former Bahamian attorney who, in 1985, had been charged with a large drug trafficking scheme involving the Columbian Medellin Cartel, and that Moo Youngs’ Bahamas-based companies were taking a percentage of the Columbian cartel’s income.

One of the Moo Youngs’ companies, Cargil International, was negotiating to purchase a Panama bank for $600m. Cargil’s office was based at the same office address as Nigel Bowe’s law office.

Mr Maharaj’s lawyers, and the former British attorney-general Sir Nicholas Lyall QC, say that Mr Maharaj was inadequately represented by his original defence team who made a string of basic errors.

The British government has issued a brief calling for a retrial after nearly 300 UK parliamentarians, from various parties, wrote a letter to the Governor Jeb Bush in 2001, asking for a retrial, saying there were ‘astonishing flaws’ in the case against him and his original trial, and Conservative MP Peter Bottomley raised the issue in the Commons.

However in February 2004 Miami judge William C Turnoff rejected an appeal by Mr Maharaj claiming innocence was not enough to warrant a retrial. He said: ‘Newly discovered evidence which goes only to guilt or innocence is insufficient to warrant relief.’

Yet as we approach the 25th anniversary of Mr Maharaj’s conviction, there is a mountain of evidence suggesting other motives for the killing and various clues that strongly suggest a miscarriage of justice.

BBC Newsnight are currently renewing their investigation amid signs that even more evidence is about to come to light which may prove Mr Maharaj’s innocence.

However there are also reasons why some people may not want the conviction quashed. If Mr Maharaj is freed it will bring into even sharper focus suggestions of a web of corruption involving the Florida justice system, a Columbian drug cartel and individuals from Caribbean, and possibly even Caribbean governments.

It is an extraordinary case, but given how high the stakes are perhaps less astonishing that Mr Maharaj remains behind bars. Mr Maharaj, who came to Britain in 1960 before making millions from a fruit import-export business at one point becoming the second-biggest racehorse owner, retains old friends who will never give up hope that justice will eventually be done.

They are determined that Mr Maharaj and the circumstances surrounding his conviction are not forgotten.