There is always an unusual distinct flavor when a director

makes a film on a tale that he or she has written from scratch. Praveen

Morchhale’s three films are such films and have shown an ability to highlight

positive bonding of people in ordinary situations and as well as in

extraordinary situations.

There is always an unusual distinct flavor when a director

makes a film on a tale that he or she has written from scratch. Praveen

Morchhale’s three films are such films and have shown an ability to highlight

positive bonding of people in ordinary situations and as well as in

extraordinary situations.

In his debut film, Barefoot to Goa (2013), Morchhale highlighted two unusual bonding situations. The first was the love of two kids for their lonely grandparents, a wistful look at the large Indian family being gradually replaced by a more impersonal nuclear family due to economic compulsions. The second was contrasting the humane attitude of poor rural folks towards kids and strangers compared with the uncaring attitudes of the urban rich.

In his second film, Walking with the Wind (2017), Morchhale chose to write a film on a school boy of modest means living in the high elevations of Ladakh, in Kashmir, trying to repair his chair in his school classroom that he inadvertently broke and desperately attempting to procure a bottle of ink critical for his sister to write her forthcoming school examinations. Nobody tells the young kid to do these acts: these are conscientious decisions taken by the school kid to act proactively without the knowledge of the school authorities or parents.Morchhale’s ability to magnify the maturity of the kid in taking responsibilities without being told to do so and ensuring his microscopic school-centred world of writing examinations remains Utopian is commendable. The family in the second film was essentially reduced further from the first film to a caring brother-sister relationship, with the parents/grandparents having much lesser roles. Morchhale’s second film recalls the early works of the late Iranian maestro Abbas Kiarostami such as The Bread and Alley. (The film was formally dedicated to the maestro in the film’s credits.) Walking with the Wind has been subsequently rewarded with recognition in India and elsewhere.

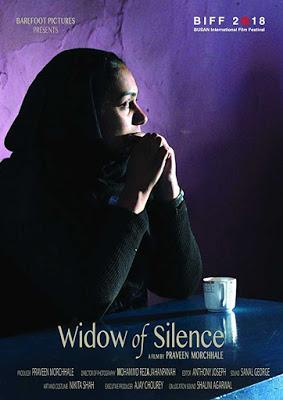

The pensive "widow" silently washing clothes.

In Widow of Silence, the third film, the writer/director further reduces the family size under the cinematic microscope, either intentionally or unintentionally. Here unlike small kids of the earlier films, there is only a single major figure—a married woman making a living working as a nurse. Her husband is missing for 7 years, and is therefore called a half-widow, as he is technically missing and not dead. She supports, from her meagre earnings as a nurse, two other members in her family: her 11-year-old school-going daughter and a semi-paralysed mother-in-law who can’t speak. As in Morchhale’s first film there is a bond between granddaughter and grandmother but the communication in this film is one way. The daughter’s presence is minimal uttering a few lines to express her loss of paternal presence and that classmates taunt her for being the daughter of a “half-widow”, who cannot pay her school fees.

The "widow's" 11-year-old daughter returns home from school

The "widow's" mute and semi-paralyzed mother-in-law has

to be tied up to a chair when she is alone in the locked house

The main story of Widow of Silence deals with the plight of half-widows where husbands go missing after they are abducted by security forces or militant groups. The lack of a death certificate creates economic and social distress for the wives. If they are attractive and young, they have to fend off suitors and predatory men.

The 7-year "absence" of of the widow's husband (in the torn photograph)

causes anguish to the widow's daughter

Morchhale’s film Widow of Silence rings true in the context of the #Metoo social upheaval unsettling the rich and the powerful. It rings true of the problems faced by the average peace loving Kashmir denizen who is not taking political stands. Who can give succour to the families who are bereft of male members to protect them and earn sufficient, steady income for the family in a unjust male-dominated Islamic society?

Morchhale’s first two films were on love and innocence; his third is on an anguished cry from the upright and marginal individual for justice and protection from predators in a democratic republic. The creation and introduction of the poetic taxi driver (Bilal Ahmad) serves as a chorus in a Greek tragedy mourning the lack of humanity and love in the once beautiful and tranquil Kashmir.

The three films of Morchhale prove a few undeniable facts.Directors and screenplay writers don’t have to look far for good ideas; the best subjects for a film can come from a keen sense of observation. Morchhale’s gambit of following the style of Kiarostami’s cinema and seeking the collaboration of the Iranian cinematographer Mohammad Reza Jahapanah for both Walking with the Wind and Widow of Silence have paid off. Jahapanah has worked for Iranian directors of repute such as Jafar Panahi as the cinematographer in his film Closed Curtain. Jahapanah recreates the Kiarostami-like visuals in the two Morchhale films shot in Ladakh and in Kashmir—the exterior long winding road shots of Kiarostami’s Taste of Cherry and the driver and co-passenger in an automobile's front seats recreating images of Kiarostami’s Certified Copy, while one of them is talking.

A long shot of the taxi in which the widow travels:

a visual touch reminiscent of Taste of Cherry

The widow sits in a taxi with flowers grown in her garden:

a visual touch reminiscent of Certified Copy

Morchhale’s gambit in investing on a talented crew for sound management and editing has made a difference. He is able to make low-cost films of international quality which his contemporary filmmakers in India have not been able to do, because those directors invest on actors instead of compact talented production crews. Morchhale brought a breath of fresh air to Indian cinema just as Anand Gandhi did by investing on a Hungarian sound designer for his remarkable Indian debut film Ship of Theseus (2012). Indian directors have lagged behind their international peers because they never saw value in acquiring talented production crews with their modest budgets. Morchhale and Gandhi did see the value and they reaped their rewards with national and international recognition. Both have made films with titles in English. Both these young directors are likely to gain further recognition in future if they trudge on the same trodden path and not deviate.

P.S. The film Widow of Silence has already won the Best Indian feature film at the Kolkata International Film Festival. Morchhale’s earlier films Barefoot to Goa and Walking with the Wind were earlier reviewed on this blog. So also were other films mentioned in this review: Certified Copy and Ship of Theseus. (Click on the coloured names of the films in this postscript to access the individual reviews.)