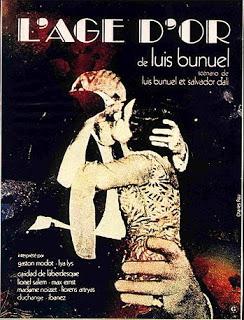

Directed By: Luis Buñuel

Starring: Gaston Modot, Lya Lys, Caridad de Laberdesque

Tag line: "A surrealist masterpiece"

Trivia: For 50 years, this film remained unavailable to the general public

L’Age d’Or (The Age of Gold) marked the second collaboration between Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali, whose first movie together was the surrealist classic Un Chien Andalou. As film historian Robert Short notes in his audio commentary for L’Age d’Or, the financial success of Un Chien Andalou was both a blessing and a curse for its makers, showing the world that motion pictures were a viable medium for the surrealist movement while, at the same time, failing to generate the reaction that Buñuel and Dali had hoped for (it’s embrace by the public was, for them, proof that the film was an artistic flop). Needless to say, they didn’t make a similar mistake with L’Age d’Or, a motion picture that both shocked and appalled audiences, critics, and even the Catholic Church.

Following a short documentary sequence detailing the physicality and behavior of scorpions, L’Age d’Or presents a series of vignettes, loosely tied together by the ongoing difficulties that a man (Gaston Modot) and the woman he loves (Lya Lys) encounter while trying to consummate their relationship. The action shifts from a religious ceremony on a remote island (commemorating the deaths of four bishops) to an aerial view of Rome (though it was actually Paris), the former hub of paganism that is now headquarters for the Catholic Church.

From there, it’s off to an upper-class party hosted by the woman’s parents, where the man, in his attempt to get close to his lover, pisses off everyone around him. After a brief, yet unfulfilling meeting with the woman in a small garden, the man, in a fit of rage, tears apart a bedroom, tossing everything from a burning fir tree to a bishop out the window. The movie’s grand finale comes courtesy of the Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom, introducing us to the four survivors of a 120-day orgy of sex and violence, one of whom, referred to as the Duke of Blangis (Lionel Salem), looks and acts an awful lot like Jesus Christ!

With imagery that is both bizarre and beautiful, L’Age d’Or takes aim at several well-respected institutions. Those in authority are mocked in an early segment, where the man, arrested for interrupting a religious ceremony with his lewd behavior, is being led off to jail. During the trip, the man presents the arresting officers with paperwork proving he belongs to a local Goodwill chapter, at which point he’s immediately released. His first act after being freed from custody was to walk across the street and beat up a blind beggar. The sometimes callous attitude displayed by society, including the time-honored family unit, is covered during the party sequence, where revelers fail to notice everything from a horse-drawn carriage parading through the main greeting area to a deadly fire that breaks out in the kitchen.

Perhaps most shocking of all is the film’s attack on religion, which did not go unnoticed by the leaders of the Catholic Church, who condemned the movie (in addition to its scandalous 120 Days of Sodom ending, the final image is that of a crucifix with female scalps nailed to it; and at one point earlier in the film, the woman, sexually frustrated, sucks on the toes of a religious statue adorning her parent’s garden).

There’s a lot going on in L’Age d’Or, some of which I didn’t understand (I’ve no idea what the symbolism was behind the cow in the woman’s bed, or why the hunter shot the child who playfully stole money from him). The film’s central message, at least as I see it, is how the various branches of authority involve themselves in the lives of everyday people, and how their often-puritan ideals prevent a free expression of love. I’ve no doubt this is at least part of what the film was trying to imply, but I’m equally as certain there were other points that went over my head.

Whatever the true meaning (or meanings) of L’age d’Or might be, one thing is certain: Buñuel and Dali (who had a falling out before it was completed, and would never work together again) evoked a reaction from all corners with this movie. A French right-wing group, known as the Patriots, was so enraged by the film that its members disrupted screenings by throwing ink at the screen, and, a while later, the Prefect of Police in Paris had the picture pulled from circulation. Finally, these two champions of surrealism had produced a work that struck a chord with its viewers, one that caused them to look at things in a way most would rather not.

This, I’m sure, made the two of them smile.