“I saw a drive in him” —Terence Fletcher in Whiplash, referring to his former student Sean Casey

“The next Charlie Parker would never be discouraged” —Terence Fletcher in Whiplash

A quick assessment of Damien Chazelle’s Whiplash would be that the film is about a music student carving out a drumming career in a jazz band. Another would be classifying the film as a tale of a musician’s long and winding journey to acquire recognition by the critics who matter. Others would only remember the film as one that forces the viewer to hate and cringe at the actions of an inhuman mentor, a perfectionist, who wrecks the lives of young creative diligent minds by physical and verbal abuse. While all these are justifiable perceptions of the film, young Damien Chazelle’s script and film offers more than the obvious.

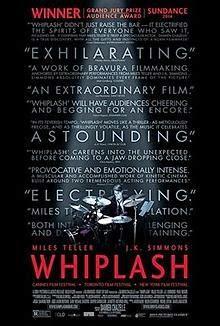

The film’s opening sequence is of the camera (the viewer’s point of view) entering a darkened corridor at the end of which the student Andrew Neimann (Miles Teller) is religiously practicing on a drum and cymbal set. Concentrating on his music, he is oblivious of all else around him. The lighting and camera movement innocuously provide the prologue for what is to follow without a word spoken. Chazelle’s poster of the film captures that very mood. The spotlight is on the drummer. And that is what could mislead the viewer. The film is equally about what is not under the spotlight, the shadowy part of the space, surrounding the drummer.

Fletcher (Simmons) (right) exacting what he wants from the drummer

The prologue over, from the darkened closed doors emerge a man in black Terence Fletcher (J K Simmons) like a cat’s stealthy entrance, followed by a defining staccato conversation and the removal of his jacket (denoting that he is at work), and an equally dramatic exit slamming the doors only to reappear again apologetically to collect his jacket. Most viewers will be transfixed by the overpowering presence of the man in black (Simmons), but a keen viewer will note the effect is totally orchestrated by the scriptwriter and director Chazelle. It is not Simmons who has grabbed your attention; it is Chazelle who is really shaking up the viewer, with the lighting, Fletcher’s clothes, the quiet entry and the loud exit. Chazelle by getting Fletcher to remove his jacket for such a short time has told the viewer that the man takes his job very, very seriously.

Whiplash is more than a movie about music; it is a lovely work exploring the ultimate Svengali bringing out the best of drumming in a wannabe using insults, intimidation, skulduggery and psychological manipulation. While Andrew takes the spotlight, Fletcher is the less assessed ogre lurking in the shadows.

Developing the Charlie Parker in a first year student with 'a drive"

The viewer is manipulated by Chazelle to hate Terence Fletcher, who does everything to ensure his jazz ensemble is the best of the best. He spots the “drive” in a former trumpet player Sean Casey when the rest of the Schaefer School of Music faculty was telling him “Maybe this isn’t for you “ (who the viewer never gets to see on screen), picks him for his ensemble just as he does Andrew the drummer, to push them to the limits psychologically and physically to bring out the best. Sean Casey ultimately becomes the first trumpet at Lincoln Center. Only Casey dies shortly after “in a car accident” according to Fletcher. Casey’s Svengali—Terrence Fletcher (Simmons)—is sorry and provides a eulogy for the departed in a touching manner by making his entire ensemble listen to a CD of Casey, with the name Sean scribbled on it playing. Evidently, Fletcher had recorded Casey’s musical output and kept the recording with him. There is a human side to the beast, who spits out venom at his students, spots the real talent and makes them famous. Much later in the film, we learn that Sean Casey did not die in a car accident but hanged himself. The spacing and timing of the two differing bits of information about Casey's death provided to the viewer is clever. The original details that Chezelle provides work as an antidote to the evil sketch of Fletcher elsewhere in the film. The revised information on Casey’s death makes the viewer to reappraise Fletcher and his tactics. So are the innocuous yet brilliant lines written by Chezelle and mouthed by Fletcher “I never really had a Charlie Parker. But I tried. I actually fucking tried. And that’s more than most people ever do.” The man in black is not all black. He too has a talent to spot the Charlie Parkers of the future and chisel them into a live Charlie Parker. And he does transform Andrew into a Charlie Parker, Andrew’s ideal musician.

Who is this Charlie Parker mentioned again and again in this movie? Charlie Parker is a legendary jazz saxophonist who often combined jazz with blues, Latin and Classical music. The recurring references to Parker in Whiplash relate to a real incident involving Parker, the jazz saxophonist. Apparently a real drummer colleague of the teenage Charlie Parker named Jo Jones threw a cymbal at the floor near Parker’s feet because Parker didn’t change key with the rest of the band (according to Wikipedia) , just as Fletcher threw a cymbal close to Andrew’s head in Whiplash. In real life that incident apparently inspired Charlie Parker to practice inordinately until he became a legend in music. In Whiplash, Charlie Parker is first mentioned over dinner by Andrew. Then you hear Fletcher wishing he had a Charlie Parker to mentor. And finally you see Andrew transform into a Charlie Parker not with a saxophone, bit with the drums. Again, if one looks at the film closely it is the brilliant screenplay that comes out trumps.

Light and shadows effectively used by Chezelle

There are aspects of the Svengali’s manipulation that one has to conjecture from what is not shown in screen. One of them relates to the mysterious disappearance of the musical notes folder of the drummer Fletcher decides is better than Andrew. Fletcher tells the band never to lose the notes. Then director/scriptwriter shows Fletcher noticing Andrew sitting by the drummer turning pages for the drummer. This is followed by the mysterious disappearance of the folder. One can only surmise that it was Fletcher who ensured the disappearance so that Andrew could play without the notes. If the viewer takes the incident to be happenstance, one is missing out on the brilliance of the screenplay (Chezelle) and editing (Tom Cross) in Whiplash.

It would be short-sighted to view Whiplash as a duel of egos between the mentor and the mentored. Whiplash is more about levelling of the egos between the two. A keen viewer will note the camera perspective that allowed Fletcher to tower over ensemble players throughout the film making a defining change in the point of view at the end when drummer seems to be looking down at the conductor Fletcher, and finally having both Fletcher and Andrew appear at the same visual level , each appreciating the other. So much is said in the film without the spoken word—in a movie where spoken word seems to be overarching at key moments. Are the words of Fletcher, “Not my tempo” more memorable in the film or the door opening precisely when second hand of the clock moves to 9 o’clock? There are invisible aspects of Fletcher the Terrible not so subtly brought on screen by the scriptwriter/director.

The Svengali in black merges with the shadows

Ironically Whiplash is competing with one another film at the Oscars that deals with another obsession of another character, that of the real life Alan Turing the mathematician turned inventor of the world’s first computer in The Imitation Game. In both films, a flat tire delays two different characters to make the films interesting. In both films, the love interests are peripheral to the tale but add considerably to the character development. Only Whiplash does it all with subtlety, an aspect bereft in the competing film. But then most audiences do not appreciate subtlety.

The shadows/lack of lighting gains importance in the final drum sequence as in the prologue as lights seems to go off before Andrews drum solo takes center stage. Fletcher is shadowed out, the ensemble is not lit, and slowly the drums are lit by the spotlight. Then follows the amazing solo by Andrew which at times are not heard (by the human ear but heard by the mind’s ear) but only seen (a brilliant exhibition of sound mixing in the history of cinema and deserving of the Oscar nomination). First, Chezelle shows us the sweat drops on the cymbals and later a few drops of blood. Fletcher is shown lending a helping hand to set Andrew's cymbals right. Fletcher takes off his jacket during the solo as in the first scene of Fletcher in Whiplash. Fletcher is in business again, he has spotted the real Charlie Parker. Such importance to details make Chezelle’s work truly amazing. The final body language between Fletcher and Andrew is one of mutual appreciation. A Svengali is sometimes needed. Somewhere in the shadows, Andrew’s dad’s visage changes from concern for his son’s physical agony to one of celebration. What a film! It is one of the finest films from USA in a long while with incredible attention to scriptwriting, editing, sound mixing (that includes patches of near silence) and cinematography. The contribution of Simmons as Fletcher is overarching in this lovely film. Chezelle deserved a nomination for direction as well, despite the Oscar snub. One wishes the 30 year old Chezelle, with just two feature films behind him, proves to be a Charlie Parker of cinema.

P.S. Whiplash is one of the author's best ten movies of 2014. It has won the Golden Globe award for Best Supporting Actor for J.K.Simmons who plays Fletcher. At Sundance Film Festival it won the Grand Jury Prize and the Audience award. The film is nominated for 5 Oscars--Best Picture, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Editing, Best Supporting Actor and Best Sound Mixing.