Tickets is a film

rarely discussed by cineastes. If it is discussed, it is often to compare and

contrast its three celebrated directors. It is therefore more satisfying to

evaluate it as a single movie more than a portmanteau film. This is a movie

that progresses in intensity of purpose from one segment to another as though

it was one director’s idea rather than of three directors and their own teams.

Tickets is a film

rarely discussed by cineastes. If it is discussed, it is often to compare and

contrast its three celebrated directors. It is therefore more satisfying to

evaluate it as a single movie more than a portmanteau film. This is a movie

that progresses in intensity of purpose from one segment to another as though

it was one director’s idea rather than of three directors and their own teams.

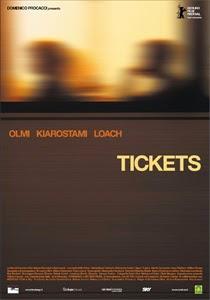

Tickets is a film that examines how different individuals react with strangers. And interestingly the film focuses on the varied reactions of Europeans on a single train journey to Rome as carefully developed by three top-notch filmmakers Ermanno Olmi from Italy, Abbas Kiarostami from Iran, and Ken Loach from UK. Each director makes the viewer think about the unusual reactions of the characters under differing conditions—all three sections carve out delectable perspectives about human nature. There is a common thread—all three segments underscore the good side of human beings and are therefore uplifting. Of course, the film can also be perceived as a political allegory of the new Europe grappling with immigration, anti-military views, and social inequality. Undeniably, all three directors have a socialist leaning.

The rich scientist about to board a train

What is most interesting to note is the gradual progression in the film from the subtle to the obvious, from the world of silence, spare lines of conversation, predominance of non-verbal communication though glances and/or stares, and discrete notes classical music (Chopin’s preludes) contrasted to the other extreme decibel level with sounds of raucous yelling and singing of the Celtic song as in a football stadium, verbal abuse, without losing the interest of the viewer in the narrative. The reverse progression would not have worked. Olmi is the master of subtlety, and naturally begins the film. Loach is the master of the “kitchen-sink” cinema with Glaswegian humor spat out like machine-gun fire and naturally deals with the end segment of the film. Kiarostami balances the two opposites—a delightful mix of some polite conversation between four sets of actors set off against an obnoxious harridan, once rich and powerful when her husband was alive, some pop music, providing the progressive transition from Olmi’s quiet cinema to Loach’s loud cinema.

The film is equally interesting as the film progresses gradually from the rich to the poor. The Olmi segment introduces us to a scientist in the pharmaceutical industry, who is rich enough to pay for two seats instead of one for his additional comfort and privacy. The second section dealt by Kiarostami deals with a woman holding second class tickets without reservations but traveling in a first class compartment. The third section deals with sections of the public who either don’t have money for their tickets or do not have money to pay the fines for a stolen ticket.

The three sections in the film are consciously or unconsciously divided into the past, the present and the future as well.

The recent past: The public relations official (Valeria Bruni Tadeschi)

ensures the scientist has a comfortable journey with a lot of care

The opening Olmi section allows for the respectable 60-year-old scientist to recall his childhood when he had heard the same Chopin piece being played by a girl whose face the scientist cannot recall or perhaps eludes his memory. He is constantly recalling the attractive public relations lady (Valeria Bruni Tadesschi, sister of Carla Bruni)) who had taken great pains to ensure he has a comfortable trip back to Rome. She has noticed him for years, but the scientist has not but is pleased to note her kindness towards him. Gentle reveries of the distant past and the recent past are shaken by the present—a sullen military official who occupies a seat opposite him and an Albanian family of limited means he can view traveling evidently without reservations between his coach and the next. Olmi nudges the viewer to evaluate the present in the context of the past. The final action of the scientist is unusual but assertive; all his co travellers in the first class coach (including a rich Indian regal family, a music enthusiast and a man cutting up news snippets from a daily newspaper) are staring at him, while the military man hides his face behind his jacket. The importance lies in the silence and stares that end the segment.

The present: The harridan who lacks sympathy

The present: A young man is forced to make a choice

The middle section from Kiarostami allows for gentle verbal communication among strangers—some characters are polite even under trying circumstances, others aggressive and repugnant. As in the first segment, glances and visual appraisal of strangers are important –but with a difference, they are longer than in the Olmi segment. But each visual and now increasingly verbal appraisal is more detailed than in the previous segment. The movie has discretely begun to change its narrative pace. The segment encapsulates several vignettes: a man insisting that a stranger is calling on his cell-phone without his permission, two men who insist on being seated in their reserved seats occupied by strangers, a young man conversing with a young girl from his own Italian town who recalls having played with him years ago, and the harridan who making the life of young male companion increasingly miserable. The future and the past alluded to in the segment matter less than the present.

The future: Decisions that can make a difference

The final Loach section is about the future as grappled by three lower middle class football crazy Glasgow young men. One of the three well-meaning youngsters seems to have lost his ticket (it is possibly stolen) and has to pay a heavy fine or face jail in Rome if doesn’t pay up. The jail term in turn would affect their jobs they hold in Scotland. Another Albanian immigrant family has possibly stolen the ticket but need it more desperately to reach their destination as it affects their lives. This segment puts the future of the two groups in perspective, with and without the tickets.

Tickets is therefore interesting to appreciate as a well-structured movie made by three directors with similar attitudes to immigration, wealth, and military/police. Olmi’s brilliant Golden Palm winner The Tree of Wooden Clogs (1978), which he wrote, directed, edited and even personally photographed was also an endearing tale on immigrant farm labourers looking at the differences between the rich and the poor in rural Italy a century ago. In Tickets, Olmi looks at the same subject of immigrants from the point of view of the rich, prodding the rich to step out of dreamy comforting images of the past into the present tribulations of the poor. In Tickets, as Olmi advances in age, it is Olmi’s son behind the camera.

The military and their lack of empathy towards poor Albanian immigrants

Kiarostami’s segment in Tickets recalls his first film The Bread and Alley (1970) in which a child encounters a hungry dog while carrying fresh bread in an alley. If one chooses to replace the obnoxious woman in Tickets with the dog in The Bread and Alley, there are several parallels. The man behind the camera is another talented Iranian, Mahmoud Kalari, who was the cinematographer for Kiarostami’s Shirin and Gabbeh and the recent acclaimed Asghar Farhadi films The Past and A Separation.

The Loach segment in Tickets is considerably helped by the cinematography of Chris Menges and scriptwriter Paul Laverty. Laverty’s collaboration with Loach has always raised Loach’s cinema, just as scriptwriter Piesiewicz collaboration with Kieslowski raised the quality of the latter’s later works. Viewers who have seen Loach’s movie The Angels’ Share (2012) will note several similarities in Tickets , including two actors common to the two movies.

A philosopher would have given the film a title such as “The Train Journey” but the film is instead called Tickets. Money and wealth-related power can be associated with the purchase of Tickets. Tickets is a ticket to evolved entertainment for an attentive and perceptive viewer.

P.S. Olmi’s The Tree of Wooden Clogs and Loach’s The Angels’ Share have been reviewed on this blog earlier.