During the 2024 JAFF, director Yandy Laurens frequently mentioned Hirokazu Kore-eda’s Nobody Knows as one of the films that inspired him; he credited the film for its masterful balance of emotional depth and understated storytelling, elements he sought to integrate into 1 Kakak 7 Ponakan in his own unique way. he even placed it among his Letterboxd’s Four Favourites. Kore-eda’s 2004 docudrama is bittersweet and painful, but beyond its poignant themes, the film brims with a humane sense and sympathy, which the Japanese auteur masterfully conveys.

Laurens’ vision for his new film, 1 Kakak 7 Ponakan (1 Brother 7 Siblings), seems deeply influenced by Kore-eda’s work. While there are clear references, this is not a mere pastiche; rather, it’s a testament to the filmmaker’ ability to internalize the tender moments that resonate with him and present them through his own lens. His frame of work is largely hopeful and positive, contrasting with Kore-eda’s more muted and somber tone. Yet, 1 Kakak 7 Ponakan is not all sunshine and rainbows or rose-tinted tragedy; it’s an exercise in tenderness—a deliberate, heartfelt exploration.

Laurens has demonstrated his aptitude for tenderness in Keluarga Cemara and Jatuh Cinta Seperti di Film-Film. However, this time he takes a more extreme approach, even by his standards, where tragedy serves as the gravitational force.

This film marks the director’ second adaptation of an Arswendo Atmowiloto story (the first being Keluarga Cemara). The film follows the transformative journey of a promising young architect whose dreams are abruptly sidelined when tragedy strikes, leaving him to care for his nieces and nephews. It’s a heartfelt depiction of the struggles and sacrifices of the sandwich generation, delicately dramatized yet profoundly relatable.

The Father, The Mother & The Brother

The film opens with a sequence that leads to a pivotal moment revisited multiple times. Moko (Chicco Kurniawan) and his nieces and nephews wave goodbye to their parents before heading to school. The scene, bathed in soft morning light, captures a bittersweet simplicity that sets the tone for the narrative. At first glance, it’s a seemingly normal gesture—a daily tradition. However, as the story unfolds, this gesture takes on profound significance. The irony of waving goodbye—a casual act often accompanied by smiles—becomes apparent when juxtaposed with the pain of parting. Laurens uses this small, poignant moment to draw the audience into the narrative, asking us to stay and observe rather than say goodbye.

Moko, a gifted architect, is on his way to defend his final assignment. After graduation, he plans to pursue a master’s degree with his girlfriend, Maurin (Amanda Rawles), and eventually open an architecture firm. But fate has other plans. His in-law passes away, and shortly after, his sister dies while giving birth to their youngest child. Suddenly, Moko’s world crumbles. His dreams are shattered as he takes on the responsibility of raising his nieces and nephews—each with distinct personalities: Woko (Fatih Unru), the nonchalant one; Nina (Freya of JKT48), who struggles to express her emotions; Ano (Nadif HS), the cheerful one; and, of course, the newborn.

Moko is forced to adjust his life, putting aside his ambitions to care for his family while trying to make ends meet. In a twist of events, his former music teacher arrives with her daughter, further complicating his situation. Moko has to take Ais (Kawai Labiba), basically non-relative, under his guidance as well.

Despite the slight age gap, Moko prefers to act as an older brother to the kids (hence the title Kakak, meaning ‘older sibling’). Yet his role extends beyond that—he simultaneously becomes their father, mother, and sibling. This multilayered dynamic echoes the Bhagavad Gita’s sentiment about omnipresence and selflessness.

Kurniawan’s portrayal of Moko stands out as nuanced and deeply emotional, revealing his ability to embody a character balancing vulnerability and strength. This is not the first time the actor portrays a role that navigates the spectrum of masculinity and femininity; he’s done it before in Pria, where he stars as a young queer. While 1 Kakak 7 Ponakan is not about sexual identity, gender roles play a significant part in the narrative, and Kurniawan embodies this complexity with finesse.

Moko’s internal struggle might initially appear naive, exacerbated by Kurniawan’s deliberate empty stares. However, this is not a character flaw, it’s more like a calculated risk by Laurens, molding Moko into a layered character. His repressed ambitions and eagerness to do everything for his family make him a human punchbag—a part of his trial and tribulation. And the film is eager to immerse the audience in this learning process.

Living someone else’s life is a resonant theme. Maurin’s efforts to save Moko might seem like blind love, but they can also be read as survivor’s guilt. She critiques Moko’s superhero complex, but upon closer inspection, we see her own reflections of this attitude. Laurens’ film plants subtle hints for hindsight observations, encouraging the audience to rethink the characters’ decisions.

Home is Where the Hearts Are

Laurens frequently captures Kurniawan in isolated frames, staring into space. These moments invite the audience to delve into Moko’s psyche—to imagine his thoughts and find solace in his solitude. As Moko observes his “siblings-cum-children” interacting in cramped spaces, the atmosphere is both burdensome and liberating. A faint, blink-and-you-miss-it smile reveals sparks of joy amidst the chaos.

Recurring imagery—such as Moko watching the children sleep together in their shared bedroom—emphasizes the siblings’ unity. This motif is both ironic and iconic, as Laurens later reveals the underlying reasoning, compelling audiences to see the blessing in the curse.

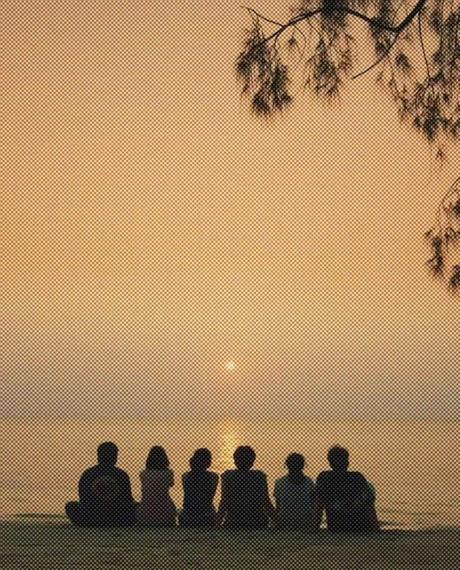

Dimas Bagus Triatma Yoga’s cinematography complements Laurens’ vision, using natural framing to capture raw emotions. A standout scene features the siblings jamming to Jangan Risaukan (transl. Don’t You Worry). The song, a hopeful anthem of resilience, underscores the film’s themes of enduring hardships and finding happiness in small moments. Sal Priadi’s ballads, woven throughout the film, further enhance its emotional depth. The camera, capturing this moment from afar, gives hints to a pivotal hint that will change the way we see the story eventually, but the mise-en-scene tricks us (or rather diverts the attention) into focusing on the human, finding humanity in them. And that’s beautiful.

This creates a striking contrast with the scenes where Moko feels confined in a home that paradoxically feels both overcrowded and empty. This duality mirrors his emotional state, amplifying the tension between the physical space and the void left by his personal sacrifices. When the film portrays the walls around Moko closing in, with his brooding eyes conveying profound fear (captured masterfully in the early video call scene), it gives away some hints of the film’s true purpose, even when it might elude viewers at first. The walls, as it turns out, were never there from the moment we first saw them (both figuratively and literally). Much like Moko, whose mind is clouded with anxiety and emotional turmoil, the film cleverly deceives the audience into adopting the same perspective. Only when the viewpoint changes do we (and Moko) finally see the reality—clear and unambiguous.

The dynamics between Moko and the other characters create abundant tender moments, brought to life by an excellent ensemble cast. Through this lens, Laurens’ admiration for Kore-eda’s humanistic touch is evident but distinct, earning its own ‘Laurensian’ identity. While some scenes veer into melodrama, most strike a perfect balance.

However, the film is not without flaws. For a significant portion, audiences may wonder why the title mentions “7 Ponakan” when it’s not immediately apparent. The revelation, though impactful, introduces a sentiment that the film suddenly requires a villainous figure to conclude the story. This plot element feels like an afterthought, a decorative addition to an otherwise well-built structure. Without having to come up with a horizontal conflict (despite maybe having a valid reference to the source material), the film is complex enough to stick with Moko’s struggle against the unexpected situation. Even if a sinister force is needed, the film could simply go on and blast the government for taking social welfare for granted — although this has always been subtly hinted at in the background. Thankfully, the film’s strong foundation upholds its integrity.

Like an architectural landmark, 1 Kakak 7 Ponakan is constructed with tender moments layered upon each other, creating not only a beautiful pièce de résistance but also a functional home — where the hearts have always been. And what a home it becomes: a solid, warm shelter for everyone willing to get invited in. A home where everything feels abundant — through thick and thin, hope and resilience.