Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, December 1950.

[Ed. Note: September 28, 2015 will mark the one-hundredth anniversary of Ethel Greenglass Rosenberg’s birth. Over the next three weeks, the Pauling Blog will explore the famous Rosenberg trial and discuss Linus Pauling’s involvement in the public debate that it engendered.]

The trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg was a source of very vocal public debate in the U.S. and around the world in the early 1950s. Charged with conspiracy to commit espionage and accused of stealing atomic bomb secrets from the Manhattan Project to give to the Soviet Union, the Rosenbergs’ trial highlighted widespread American fears that the Soviets were quickly catching with the United States in terms of technological prowess, and that these gains might be attributed, at least in part, to the assistance of unloyal Americans.

The trial also bore many of the hallmarks of a sensational media event. It included defendants who maintained their innocence no matter how hard they were pressed, the public airing of a family feud, and potential court appearances from celebrated atomic scientists and a “Red Spy Queen.”

The Rosenberg trial might now be viewed as both a piece of a larger quest to uncover Soviet spies in the wake of World War II and an outgrowth of the fear of communism that so characterized the Cold War. What is certain is that event sparked outrage nationally and internationally, inciting involvement and protest from a wide range of actors, including Linus Pauling.

David Greenglass.

The Rosenberg trial was actually just one high-profile event among several others that came about as the U.S. security apparatus sought to identify “atom spies” in its midst. One such individual, Klaus Fuchs, a German-born British physicist, was convicted on March 1, 1950 after willingly granting interviews detailing his involvement. His testimony prompted a larger investigation into potential spies at the Manhattan Project, as his statements suggested that someone else in the project had been supplying information to the Soviets before Fuchs did around 1942.

Fuchs’ testimony led to the discovery of Harry Gold, a key witness in the trials against David Greenglass, and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. Gold was identified as the courier for information supplied by Greenglass at Los Alamos, which he then passed on to Julius Rosenberg. Gold served fifteen years in prison for espionage, while Fuchs was charged with four counts of supplying secrets to an allied country during war. (Importantly, this distinction of the Soviet Union as an ally was made in England, where he was tried.) Fuchs was ultimately sentenced to fourteen years imprisonment, of which he ended up serving nine years and four months.

Greenglass, a machinist working on the Manhattan Project in Los Alamos and the brother of Ethel Rosenberg, was arrested on June 15, 1950. His arrest prompted Julius’ initial interview and the surveillance that followed. Julius was arrested on July 17, 1950 after being interviewed on June 16. Ethel was arrested one month later, based largely on new testimony given by her brother on August 11. In this August statement, Greenglass specifically pointed out that his sister, Ethel, had typed the notes that were delivered to the Soviets, and not his wife Ruth, who had been identified in Greenglass’ original interview.

Greenglass and his testimony served as the foundation for the prosecution’s case. It was Greenglass’ claim that Ethel had typed the notes that he made from knowledge gleaned at Los Alamos. These notes were then given to Anatoly A. Yakovlev, the Soviet vice consul in New York City, through the courier Harry Gold. Many years later however, Greenglass confided to author Sam Roberts – who was researching his book The Brother – that indeed it was most likely Ruth who had done the typing and not Ethel. In 1950 Greenglass had implicated Ethel to spare the life of the mother of his children, choosing to sacrifice his sister in the process.

Greenglass’ decision to change his testimony and accuse his sister Ethel rather than his wife Ruth came as a welcome turn of events for government prosecutors, who believed that they could use Ethel as a lever against Julius and force him to give up more names by charging her equally with him. However, this tactic did not work as planned, as Ethel committed to stand by her husband and refused to incriminate herself or anyone else. During their sessions in court, both of the Rosenbergs upheld their Fifth Amendment rights and refused to divulge other names or admit to Communist Party ties in the past.

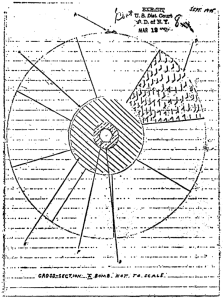

Greenglass’s sketch of an implosion-type nuclear weapon, ca. September 1945.

The specific information that was alleged to have been relayed to the Soviets, per Greenglass’ testimony, can be divided into four categories:

- General information about the layout of the labs at Los Alamos and potential recruits working on the Manhattan Project.

- Description and a sketch of the lens molds that were used in experiments of the implosion-type bomb.

- Description of what Greenglass referred to as a naval-type bomb, which was the type dropped on Nagasaki.

- Description and a sketch of an experiment to determine a reduction in the amount of plutonium or uranium needed to construct an atomic bomb.

The evaluations required in arguing and adjudicating the Rosenberg trial were complicated by a wide variety of factors; even discussing certain allegations in an open court proved problematic, as much of the information under review was classified.

Most importantly, because the Rosenbergs had been charged with conspiracy, there did not need to be any concrete evidence against them to arrive at a verdict of guilty. And indeed, over the course of the trial, no evidence was ever produced that showed that the couple had successfully passed information on to the Soviets.

While treason is one of the hardest crimes to prosecute, conspiracy is among the easiest. Hearsay testimony can be admissible in a conspiracy case, and once a conspiracy has been proven to exist, all members involved can be held accountable for the actions of the others regardless of their knowledge of others’ acts. In addition, the success of a conspiracy does not have to be proven, only that those involved conspired towards an agreed upon goal.

The lack of concrete evidence presented in the trial combined with the media frenzy surrounding the proceedings to incite strong feelings among the public. As the trial moved forward and sentences were issues, many would come to believe that the punishments handed down were excessive, regardless of innocence or guilt, and that the process used to arrive at a verdict was deeply flawed.