An image of the April 24, 1971 March on Washington, as held in the Ava Helen and Linus Pauling Papers. The Paulings participated in a companion march held in San Francisco that same day.

[Pauling and the Vietnam War, Part 7 of 7]

“The American people are now learning the truth about the war…our entry into it on a great scale without even a request from South Vietnam…the corruption, the complete absence of a rational and moral goal…and the American people are now determined to bring this madness to an end.”

-Linus Pauling, 1969

In September 1969, Ho Chi Minh died at the age of seventy-nine and was replaced by Premier Pham Van Dong. At this same time, the anti-war movement was gaining considerable strength in the United States. In October, a “Vietnam Moratorium Day” was declared, during which students and faculty alike walked off of campuses across the country to talk about the war with members of their community.

At Stanford University, Linus Pauling, who had recently taken a position there as a visiting lecturer, was a central figure in this event. On the evening of the moratorium, he delivered a speech in which he proclaimed that the American people were finally learning the truth about the Vietnam War and the United States’ “cold blooded” ambition to retain control of Southeast Asia as part of a Western capitalist “economic sphere.” He delivered a similar message a month later in a talk given at Huntingdon College in Montgomery, Alabama. A story on the event, published in the Montgomery Advertiser, quoted Pauling as follows:

We – you and I and the majority of Americans – who are going to stop this war, are now face to face in opposition to the small group of rich and powerful people who are using their power to keep the war going, year after year: the people who benefit from the war, the military-industrial complex, the Pentagon and the war contractors who get the 15 billion dollars per year of excess profits on the guns, bombs, Napalm, planes and other instruments of war; and also the politicians, such as President Nixon, who are indebted to them.

The United States’ new President, Richard Nixon, had begun the troop withdrawals that he had promised on the campaign trail the year before. His plan, dubbed the

Nixon Doctrine, was to build up the Army of South Vietnam to the point where they could take over the defense of their own country. This policy came to be known as “Vietnamization.” Meanwhile, China and the Soviet Union continued to supply the North Vietnamese – and by extension the National Liberation Front – with aid. By 1970, Nixon announced that 150,000 U.S. soldiers would be withdrawn over the next year, thus reducing the American troop presence by about 265,500 people from the time when he had entered office.

However, at the same time, Nixon ordered a massive increase in bombing along the Vietnam-Cambodia border, and likewise redeployed many of the withdrawn troops to areas along the coast or just outside of Vietnam. These actions incited huge protests by those outraged by the President’s apparent subversion of his promise to de-escalate the war effort.

Pauling was among those who protested, speaking out in particular against the bombing incursions into Cambodia. While attending a benefit in support of the McGovern-Hatfield Amendment to End the War, Pauling also declared that it had made him “sick” when Nixon stated before Congress that he would draw down troop numbers, and then, “five days later,” sent aircraft and ground troops to Cambodia. In response, Pauling suggested that everyone in the Bay Area “get sick” and take a week off of work. He explained his rationale as such:

When everyone is sick, the work stops, the economy is slowed down. If there is such an epidemic here, during the next week, it might spread over the whole country! Let our slogan be, “We’re sick of the war.”

Illness of another sort was also on Pauling’s mind. Around the same time that he proposed calling in sick to work, Pauling also recorded a radio address for KPFK-FM in Los Angeles on the subject of defoliant use in Vietnam. By 1968, he explained, 500,000 acres of cropland had been destroyed in Vietnam through the use of herbicides, some of which contained arsenic compounds. Not only did this action purposely lead to the starvation and death of civilians – especially the young and elderly – but Pauling attested that four scientists returning from South Vietnam with samples of food, hair, mother’s milk, and other substances had found them to be contaminated by these highly toxic herbicides.

Moreover, some of the herbicides being used in the war effort were not only very lethal but also very stable, and Pauling emphasized that these poisonous compounds would remain in the ecosystems of Vietnam for many years. Pauling further pointed out that several of the herbicides had been developed deliberately for the purpose of crop destruction as a tool of war by E.J. Kraus, the chairman of the Botany department at the University of Chicago. Pauling saw this as a violation of the proper role of university research, and cast aspersions upon the influence that the military and corporate war profiteers alike were gaining with respect to his academic colleagues’ research agendas.

The Paulings at an unidentified peace rally, possibly the April 24, 1971 San Francisco companion event to the March on Washington.

As these and other horrors of the Vietnam War gained increasing media traction, the anti-war movement, and the concurrent withdrawal of troops, continued. In 1971, Australia and New Zealand withdrew their complements of soldiers, and the American troop count was likewise further reduced to 196,700, with the return of an additional 45,000 troops promised for 1972. But even as this significant drawdown in ground forces was underway, significant U.S. naval and air might remained in the Gulf of Tonkin, as well as in Thailand and Guam.

From Pauling’s perspective, the major problem now hampering on-going peace talks in Paris was President Nixon’s continuing support of Generals Thieu and Ky of South Vietnam, political figureheads who had been put into power following a United States-sanctioned coup that had resulted in the assassination of the previous leader, President Diem. Both the North and many citizens of South Vietnam now refused to acknowledge these men as representatives of the provisional government of South Vietnam, and negotiations predictably suffered as a consequence.

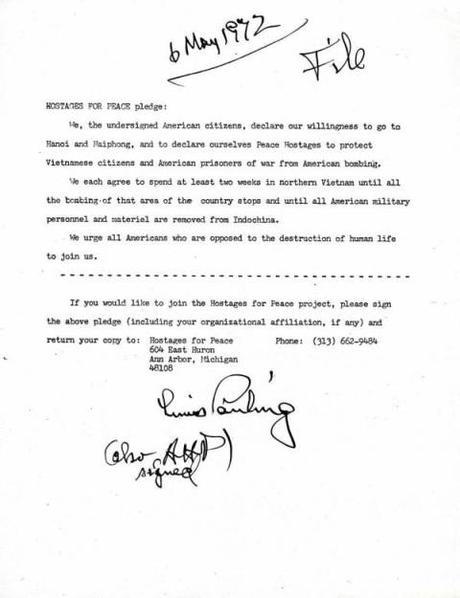

In May 1972, a group based in Ann Arbor, Michigan and calling itself Hostages for Peace organized an extraordinary measure in an attempt to curb the violence in Southeast Asia. The group circulated a pledge which read as follows:

We, the undersigned American citizens, declare our willingness to go to Hanoi and Haiphong, and to declare ourselves Peace Hostages to protect Vietnamese citizens and American prisoners of war from American bombing. We each agree to spend at least two weeks in northern Vietnam until all the bombing of the area of the country stops and until all American military personnel and meteriel are removed from Indochina.

Linus and Ava Helen Pauling signed this pledge, agreeing to use themselves, effectively, as human shields against further American bombardment of North Vietnam. It was a courageous and potentially deadly commitment that the couple would, thankfully, not be called upon to realize.

“Hostages for Peace Pledge.” May 6, 1972.

On January 15, 1973, just weeks after a major bombing offensive had decimated what remained of North Vietnam’s economic and industrial capacity, President Nixon ended all military action against the North. The Paris Peace Accords were signed twelve days later, officially ending direct U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War. A cease-fire was subsequently declared across North and South Vietnam, and U.S. prisoners of war were released. The agreement guaranteed the territorial integrity of Vietnam and, like the Geneva Conference of 1954, called for national elections in the North and the South.

In other words, the conditions that Ho Chi Minh had made clear to Linus Pauling in 1965, and which Pauling had argued in favor of for the past eight years, had now been codified as an international agreement. In that time, it is estimated that anywhere from 800,000 to just over a million Vietnamese soldiers and civilians on all sides were killed, in addition to 200,000 Cambodians and 60,000 Laotians. Over 58,000 U.S. soldiers also lost their lives, with more than 1,500 still missing in action.

Tragically, like the Geneva Accords before them, the Paris Peace Accords were quickly broken. In 1974, the Viet Cong resumed military operations, and South Vietnam’s President Thieu declared that the Paris agreement was no longer in effect.

But this time, no American help arrived. In 1975, President Gerald Ford requested that Congress fund the re-supply of South Vietnam to defeat the National Liberation Front, who were now aided by a formal North Vietnamese invading force that was well-equipped, in large part, by other communist countries. Ford’s request was refused, and on April 27th, 100,000 North Vietnamese troops encircled Saigon, shelling the city while American helicopters evacuated vulnerable South Vietnamese citizens until the North’s tanks finally breached the lines of the South Vietnamese Army and captured the city.

In July 1976, North and South Vietnam were merged to form the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and, over the next ten years, more than one million South Vietnamese were sent to reeducation camps, with as many as 165,000 dying as a result.

After the war’s end, Linus Pauling carefully filed away the letters, the posters from various protests and anti-war lectures, and the memories of a long and bitter conflict. Included in these papers was correspondence concerning the Democratic Republic of Vietnam’s 26th celebration of nationhood in 1971. Though he was not in Hanoi for the event, Pauling had been in contact with a group that was, National Peace Action Coalition representatives Judy Lerner, David McReynolds, James and Patricia Lafferty, Joseph Urgo, and Ruth Colby.

The group had been met by the Peoples’ Coalition for Peace and Justice of North Vietnam, which hosted their visit. At the birthday celebration, where Premier Pham Van Dong declared the regime of the south fascist and called for the peoples of Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos to unite to gain, “freedom, independence, peace and friendship, happiness and prosperity” for all of Indochina, the Americans were invited to make a statement of their own. Taking the stage, they articulated their feelings as best as they could:

No words of ours can fully express how deeply we have been moved by the way in which we have been received. We, citizens of a nation that has brought such terrible suffering to the peoples of Indochina, have been received as friends. The people of Vietnam understand that it is the rulers of the United States and not its citizens who are the enemy of the Vietnamese. One of our members is a veteran of the Vietnam War, and it would have been natural if he had been received with hostility. Instead, the guide in the War Museum embraced him with tears in his eyes – a simple human encounter which lifted both men above the level of being Vietnamese or American, to the level of brothers who suffered together in this, the most tragic war America has ever waged.

As North Vietnam celebrated its independence – an independence that had never been gained by South Vietnam – the American delegation in Hanoi affirmed again that, as the anti-war movement in the United States continued to swell, they would do everything in their power to end the conflict. This was a cause to which Linus and Ava Helen Pauling likewise devoted considerable energy over a full decade, and one that ultimately – through the pressure placed upon the governments involved by many such individuals throughout the world – played an important role in ending the Vietnam War.