Birds of a Feather Sing Together

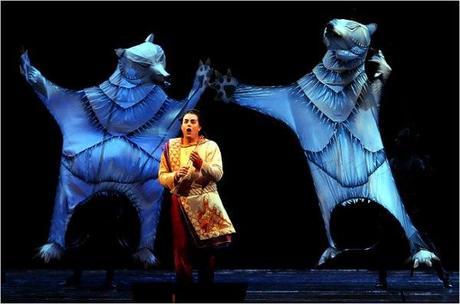

Papageno & Dancing Flamingos (Ken Howard/Met Opera)

If movie and theater director Julie Taymor struck out with Spider-Men and Green Goblins, she had much better luck elsewhere with lions, tigers, and bears (oh my!). Seven years after her fabulous 1997 hit, The Lion King, dazzled Broadway audiences, Ms. Taymor hit her stride with a thoroughly entertaining, sumptuously staged, geometrically-arranged rendition of The Magic Flute.

The Metropolitan Opera revived her 2004 production of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s final work for the stage in a condensed English-language version for boys and girls of all ages. Featuring a number of elaborate cartoon-like figures — i.e., dancing lady flamingos and impressive mammoth-sized bruins (but no alligators or hippopotamuses, thank goodness) — this family-friendly diversion proved a treat for listeners in the first radio broadcast of the New Year, given last Saturday afternoon on January 4, 2014.

The Magic Flute, or Die Zauberflöte as it is known in the original German, comes from a tradition of suburban theater presentations described as “magic opera.” One part farce, one part frolic, and several parts rollicking revue, with a number of special scenic-effects scattered between moments of high-mindedness, this two-act pageant (the Met presented its version in one continuous act) came at the tail end of the Austrian composer’s busy life.

The premiere took place in Vienna on September 30, 1791. A little over two months later, Mozart was no more. Although reviews of those performances are non-existent, by all accounts (mostly word of mouth) the opera was a phenomenal success. Wolfgang had the time of his life conducting the score from the pit while his librettist, the barnstorming singer, sometime playwright and actor, and full-time impresario Emanuel Schikaneder, pranced about the stage as the flamboyant birdman, Papageno.

No fool when it came to the theater or his public, Schikaneder was clearly attuned to the popular tastes of his time. As a consequence, he asked his old friend and fellow Freemason Mozart to compose the music for a proposed comic extravaganza, which soon took on humanistic overtones. He even wrote a nice, fat part for himself, a pleasant little bonus for a performing artist, wouldn’t you say?

The opera — actually, a Singspiel, which stresses spoken dialog over sung recitative — derived from several sources, including a collection of Oriental tales compiled by Christoph Martin Wieland, and a contemporary stage play, Kaspar the Bassoonist or the Magic Zither [sic], by Schikaneder’s chief rival, an individual named Marinelli.

Despite the tomfoolery present in Milos Forman’s 1984 Oscar-winning film adaptation of Peter Shaffer’s play Amadeus, the opera enjoyed a vogue among serious musicians. Why, Beethoven himself held it in high regard as a worthy stage vehicle. More than that, it’s a supreme challenge to directors and producers alike. The principal roles are no pushover, either. Any artist who believes The Magic Flute to be a “walk in the park” is in for a very bumpy ride indeed. In order to pull this opera off, the cast must be comprised not only of decent singing actors (both comic and serious), but of superbly trained musicians as well.

Nathan Gunn as Papageno (nytimes.com)

Fortunately, the Met had an ample supply of them, starting with the audience’s favorite, baritone Nathan Gunn as Papageno. Gunn, who’s been busy of late performing in such Broadway classics as Carousel, Camelot, and Showboat, was the splitting image of a walking, talking (and humming!) bird-catcher dude.

A Mr. Green Jeans-wannabe, his Papageno was so infectiously appealing, so charmingly charismatic, and so immensely likeable, that Gunn aroused the audience’s sympathy merely through his sighing. You can catch his performance of the part on the DVD/Blu-ray edition of this production with other Met artists. But for me, no matter whom Nathan Gunn appears with, all eyes and ears will be on his Everyman Papageno — as funny, sad, amorous, playful, deceitful, and human a trod-upon soul as I’ve seen or heard.

The part was tailor-made for Gunn’s talents, and he did not disappoint. From his engaging entrance song, “I’m Papageno, That’s My Name,” to his feigned suicide attempt, this birdman took off on feathered wings in high-flying vocal fashion.

His counterpart, Papagena, played and sung by soprano Ashely Emerson, was every bit his acting equal. She and Gunn made beautiful music together in their delightful duet near the end (“Pa-pa-pa, Pa-pa-pa”), while Ashley’s laughter-inducing speaking voice as the Old Lady provoked snickers from the younger members of the audience. And, most important in such a dialogue-heavy piece as this, every word the couple spoke was clearly and audibly enunciated.

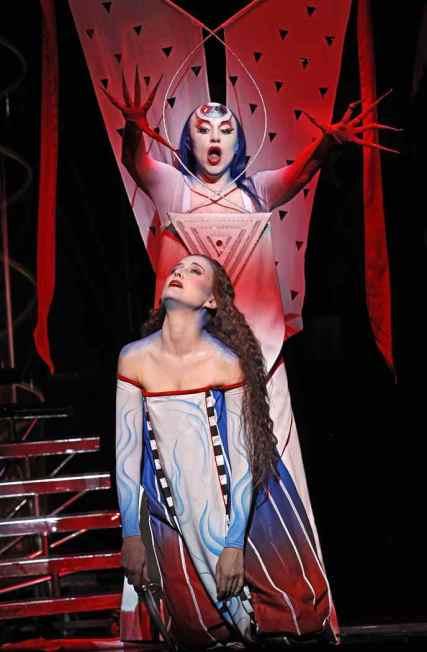

Tamino & the Bears (nytimes.com)

Alek Shrader’s Tamino was persuasively delivered, too, although I sensed a bit of tentativeness as he approached some of his notes. The sound became more constricted the higher up the scale he ventured, although his first-act aria, “This Portrait’s Beauty,” wherein he praises Pamina’s loveliness, was earnestly phrased. In addition, his diction was well-nigh perfect. Shrader was the English-language Count Almaviva in last year’s abridged edition of Rossini’s The Barber of Seville, with lyrics and text by poet J.D. McClatchy, who also provided the English translation for The Magic Flute. I wasn’t especially enamored of The Barber, but The Flute rang truer for me this time around.

This year, the tenor repeated the feat by excelling in the part of Tamino, who goes off in search of the supposedly kidnapped Pamina. Along the way, he meets up with any number of various and sundry individuals, among them the birdman Papageno, the Three Ladies in Waiting, the vengeful Queen of the Night, a wicked blackamoor named Monostatos, an aged Speaker, the High Priest Sarastro, Two Armored Men, and a certain magical flute.

His Pamina was elegantly sung by soprano Heidi Stober. She drew much applause for the poignancy of her second-act number, “Now My Heart is Filled with Sadness,” bemoaning the loss of Tamino’s love. Stober wrung every ounce of emotion and pathos from this piece as could be expected, without letting it turn mawkish.

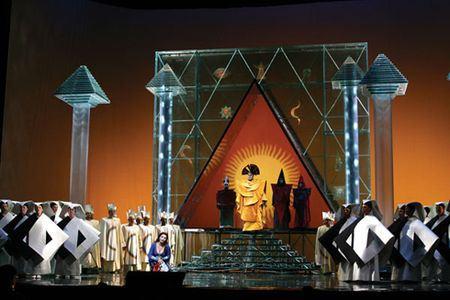

Pamina & the Queen of the Night (Photo: Jeff Busby)

Her mother, the evil Queen of the Night, was taken by coloratura Kathryn Lewek, who was up to the challenge of this brief but demanding role from the get-go. Her introductory aria, “My Fate is Grief,” gave only the barest hint of what was to come. It constantly amazes me how anyone can sing those sixteenth notes in alt without pausing for breath. Lewek hit every one of them fully and solidly, while sailing through this vocal and histrionic exercise with flying colors. She received the loudest and most prolonged ovation of the day for her superbly rendered “Vengeance” aria.

The remainder of the cast included the mellow-voiced Sarastro of bass Eric Owens, who plumbed the role’s lowest notes to fine effect in his aria, “Within Our Sacred Temple”; bass-baritone Shenyang as the dramatically alert Speaker; tenor John Easterlin as a comically devious Monostatos (who threw out the opera’s funniest line, “If I can’t have the daughter, I’ll try the mother,” with exaggerated relish); Wendy Bryn Harmer, Renée Tatum, and Margaret Lattimore as a mellifluous trio of Ladies in Waiting; Thatcher Pitkoff, Seth Ewing-Crystal, and Andre Gluck were appropriately “in tune” as the Three Boy Spirits who get to ride around on a floating cloud; and Anthony Kalil and Jordan Bisch sang what was left of the Two Armored Men.

Finale to Act 1 – The Magic Flute

Lest we forget, this was an abridged Magic Flute. And as such, about an hour or more of the music was trimmed from this sparkling score, to say nothing of the lengthy passages of spoken dialog that were snipped away and re-calibrated for the kiddie crowd.

The most regrettable cut of all, however, was the missing overture: a resoundingly showy piece of music, it’s one of Mozart’s finest compositions. Overlooking this glaring omission, British conductor and early-music specialist Jane Glover led a highly-polished reading of the opera in buoyant, stiff-upper-lip fashion. In fact, there was little to find fault with in this revival, which proved a great start to the New Year’s opera season. A Happy 2014 to all!

Copyright © 2013 by Josmar F. Lopes