A “Slave ” to Passion

Carlos Gomes in his later years (memoriadaopera.blogspot.com)

In 1880, the ill-tempered, disillusioned, and financially hard-pressed Carlos Gomes returned to native shores, where, by his own account, he was greeted “like a prince” and treated “like a king.”

He immediately set to work on several new projects, all of which were prematurely aborted for one reason or another, thus repeating a pattern of fits and starts first displayed back in Milan. It was during this same period that his fellow Brazilians became fully cognizant of his stage works, due in part to the slew of productions Gomes had personally supervised while on extensive tour there.

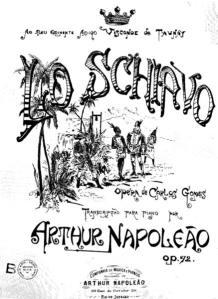

Traveling to and from Italy, he put the finishing touches to his next opera, Lo Schiavo (O Escravo, or “The Slave”), which debuted in Rio, on September 27, 1889, to wide acclaim. Based on “a hurried five- or six-page draft” by his good friend, the liberal activist Viscount Alfredo d’Escragnolle de Taunay, the scenario called for an African slave named “Ricardo” to participate in the epic struggle against slavery in Brazil circa 1801, no doubt a powerfully authentic tale — a little too authentic, in the eyes of some.

At the insistence of librettist Rodolfo Paravicini and publisher Giulio Ricordi, the black slave would be transformed into the Tamoio Indian “Iberê” in deference to the continuing European taste for “exoticism” in art music. Additionally, the time of the action was pushed back some two and a half centuries, purposely dulling the effect of the more relevant slavery issue and resigning the drama to the long-ago plight of defenseless South American natives and their brutal Portuguese colonizers.

In short, it was all a rather diaphanous attempt to recapture the glory years of La Scala by recycling some of Guarany’s previous plot threads. Doubtless the composer had been spoiling for a comeback, wherein his mounting financial obligations would finally be met and his future employment secured; consequently, he conceded to these changes without much of a fight. The catch, however, was that Lo Schiavo was never performed in the Italian mainland during his lifetime. It had been tentatively scheduled for Bologna, but due to Gomes’ continuing cash-flow problems and simultaneous legal action by Paravicini to prevent him from inserting his polemic Hino à Liberdade (“Hymn to Liberty”), with words by a different poet, into the score, the engagement was abruptly cancelled.

Adding insult to his injuries, Gomes broke free of Casa Ricordi’s constraints. He had reached the unavoidable conclusion that once the publishing house had secured the services of its newest discovery — one Giacomo Puccini, a fast-rising talent from Lucca — it perceptibly lost interest in the problematic Brazilian. From here on, Gomes would have to go it alone in the publishing world without Ricordi’s backing. In retrospect, he was no worse off for leaving Casa Ricordi than if he had stayed with them from the outset.

Still, why would the appearance of a black-African male figure on the Italian stage have caused such a stir, in light of the sympathetic treatment wise, old maestro Verdi had given his Ethiopian princess Aida, or the Moorish general Otello, for that matter? The only explanation one can arrive at is a none-too-subtle hint of racial prejudice: Indians battling settlers was one thing; but black slaves seeking independence from their masters may have hit too close to home for nineteenth-century audiences to accept.

We should not be at all surprised that the composer’s freedom-loving “Slave” was being treated no differently in his second homeland than Gomes himself had been treated of late. The experience of producing the opera was a most painful one for his friend Taunay to be embroiled in as well. Profoundly disappointed with the whole manipulative affair, Taunay repudiated any claim of authorship to the work — a situation that, almost 70 years later, would call to mind a similar act performed by poet-musician Vinicius de Moraes, after the Brazilian premiere of the 1959 movie Black Orpheus.

Negotiations to bring the new opera to Brazil, where the political climate was no better, commenced almost immediately. These were long and drawn out, and eventually necessitated the direct involvement of Emperor Dom Pedro and his daughter, Princess Dona Isabel, who helped inject much-needed capital into the proceedings — to the absolute displeasure of the anti-royalists.

Cover page of the piano score of Lo Schiavo

In spite of the various setbacks, however, the opera’s long-awaited first night was a smashing success. Along with its predecessor Guarany, Lo Schiavo is but one of only a handful of works in the entire active repertoire that have even treated or addressed Brazilian-based subject matter, in this instance the politically charged, hot-topic issue of slavery. The Gazzetta Musicale, Casa Ricordi’s representative voice in Milanese circles, dispatched its critic to Rio to deliver a favorable verdict, for once, on one of Gomes’ finest achievements: “…this Slave has many times the enchantment of musical might; it is ardent, imaginative, and moving, it draws you in and convinces. The ‘Hymn to Liberty’ is one of those fresh and spontaneous inspirations that [should] serve to popularize its author.”

The most curious description of the piece came, astoundingly enough, from Brazil’s Veja na História magazine: “A pity that the music’s sparkle is distorted by the grotesque image of semi-nude tenors in improbable mustaches, singing in Italian, an example of which occurred in Il Guarany. Indians in place of Negro slaves is difficult enough to take – but an Indian in a mustache is just too implausible.”

Facial hair or no, the melodic advancement Gomes showed in his writing of Lo Schiavo has never been equaled by him in his remaining works. Similar to Peri, the juicy starring part of Iberê is a favorite among baritones. The opera itself was dedicated to Her Serene Princess Dona Isabel, who had earlier signed the Lei Áurea, or “Golden Law,” into existence, abolishing the institution of slavery. Bolstered by that now-historic event and by Lo Schiavo’s impassioned ex-post-facto appeal, her father, the emperor of Brazil, decorated his most “faithful and reverent subject,” Carlos Gomes, with the title of Grand Dignitary of the Order of the Rose, and so much as promised him the directorship of the reconstituted Music Conservatory in Rio de Janeiro.

A Revolting Development

Unfortunately for the composer, the atmosphere in his home country was rife with revolution. In all, the bloodless coup d’état that resulted had altogether rocked Gomes to his very foundation:

“The shock that affected my heart, which was so devoted to the Royal Family, was so great that to this day I have yet to completely recover. My health has suffered greatly, even to the point of my body losing its balance. I cannot describe my profound sorrow, the reality of which appears to me more like some horrible dream that such a thing could take place in my native land… God forgive the perpetrators of this brutal act and, at the same time, protect the Brazilian nation and its people.”

By November 15, the Proclamation of the Republic was all but a fait accompli. The aging sovereign Dom Pedro II, the very symbol of Old World aristocracy and the ruling elite, was deposed and unceremoniously shipped off to Portugal. As a recipient of the benevolence and generosity of the now-exiled monarch, Gomes lost his yearly stipend, which he had been accustomed to receiving for nearly three decades. Because of his diminished economic status and personal connection to his royal patron — and amid unremitting allegations of his having squandered the emperor’s money while “living it up” in Europe — he was forced to temporarily leave Brazil. “They don’t even want me as the doorman,” the composer complained in an 1895 letter, written long after he had been passed over for the job of director, “because the government wants Miguez to be there.”

Leopoldo Miguez, a European-trained musician and composer from the city of Niterói, near Rio, had been chosen as the new head of the Music Conservatory. A disciple of Wagner and Franz Liszt, he became the New Republic’s man of the moment. As overtly political as this appointment appeared to be, Gomes’ unguarded praise for his former benefactor did his cause no justice and likely contributed to the Conservatory’s decision to go with Miguez. “I come from a barbarous race,” Gomes grumbled to his editor, “yet I am grateful until death to him who deigned to appreciate me, above all as a man.”

Statue of Condor at Praca Ramos de Azevedo, Sao Paulo (Antonio de Andrade)

Placing his tail strategically between his legs, Gomes clawed his way back to La Scala — the last time he would associate himself with that venerable institution — to fulfill a contract for a new work: the oriental-themed Condor, his own variation on those exotic stage pageants that were all the rage in Europe. Given in February 1891 to much local fanfare but very little monetary recompense, it nonetheless racked up a fairly respectable number of performances, and against some remarkably stiff competition that included Wagner’s Lohengrin. The appearance of the opera a year later in Rio, with Romanian soprano Elena Theodorini as Odaléa, left Brazilian audiences cold. Sadly, the year 1891 ended with the death in France of his most ardent supporter, Dom Pedro II, thus sealing the composer’s financial fate.

As a test of his allegiance to the new order, he was invited by the recently-installed government to write an appropriate musical theme for the occasion. Surprisingly, Brazil’s most revered classical musician turned down the monetarily lucrative offer. Quite rightly, Gomes felt that his closeness to the dethroned ex-ruler should have excused him from taking up such a disloyal (in his eyes) commission; that being the case, his overtly righteous tone about it all played right into unscrupulous hands. Where he did the most damage was to his own long-term career prospects: by refusing the government’s one and only handout, he shot his chances for further advancement in the foot, as well as cleared the way for Miguez to be accorded the honor.

America Discovers Columbus

For the upcoming Fourth Centennial Celebration of the Discovery of America, Gomes contributed the four-part oratorio Colombo, which he dubbed a “symphonic poem with chorus.” One of his most ambitious and fully evolved large-scale compositions, it premiered in Rio de Janeiro on October 12, 1892 — Columbus Day, to be exact — to generally negative reviews. Desperate for new sources of revenue, Gomes had earlier grasped at the chance to present Colombo in two separate venues: one, a contest sponsored by the city of Genoa, the Italian explorer’s home port; the other in Chicago, for the International Columbian Exposition the year after. It lost out on both counts to others.

Rehearsal of Colombo at the Teatro Municipal, Sao Paulo (Tiago Quieroz / AE)

Gomes may have run afoul of partisan politics, but there was something else besides the writing of his symphonic poem that caused the cantata to be dropped so quickly from competition. Apart from its celebration of a major past event, this lushly orchestrated and lyrically refined masterwork re-enacted, in musical terms, his earliest encounters with the emperor and empress of Brazil, in the historical personages of Christopher Columbus, the Spanish King Ferdinand of Aragon, and his headstrong spouse, Queen Isabella of Castile. The scene in Part Two, in which Columbus tries to entice the monarch with his dreamlike vision of a sumptuous New World; followed by Isabella’s prodding of her irresolute spouse to finance the explorer’s questionable sea venture, mirrored that decisive point in Gomes’ own life when he was presented with the opportunity for study abroad, along with the more recent behind-the-scenes controversy involving the Brazilian staging of his “Slave.”

This final show of gratitude to the late emperor and his wife for their favor and trust in his abilities did not sit well with republican sympathizers. By and large, they were as outraged by the composer’s obliging attitude toward the royals as the abolitionists had been with the ludicrous alterations to Lo Schiavo’s plot. Who was the real slave to special interests, they pondered warily, the opera’s title character or the composer himself? Their uncompromising view of his work practically guaranteed that no such favor and trust would be forthcoming from the current administration — of that, Gomes learned firsthand.

Tired of waiting for authorization to participate in the International Columbian Exposition, Gomes used his own severely limited resources to journey westward from Europe to the Windy City. In September 1893, he caught up with his country’s delegation, which paid little heed as he scurried about preparing for what he had imagined were fully-staged performances of Guarany and Condor. However, when an “expected” subsidy from the Brazilian government failed to materialize — the result of political foot-dragging for his unofficial attendance at the fair — the put upon composer was forced to give free public concerts of excerpts from his works instead.

So what were his lasting impressions of an Industrial-Age Middle America? In a letter from that period, written in the United States to a colleague in Italy, the exasperated Gomes complained:

“The presentation in Chicago of Guarany came to nothing… I had hoped to make a world of contacts, but too late I realized the sad truth. In this country, art is a myth. Americans are only interested in new and practical matters, that is, in the easiest methods for making money!”

(End of Part Three)

Copyright © 2012 by Josmar F. Lopes