Linus Pauling’s involvement in the peace movement, and particularly his circulation of what is now know as the United Nations bomb test petition, made him doubly famous: he was no longer just a scientist, but a humanitarian as well. This fame came at a price though, as his peace efforts did not always receive the positive acclaim afforded much of his scientific work. In an era of McCarthyism and Cold War fear of communism, his activities were sometimes viewed as a threat. Despite Pauling’s attempt to foment nonpartisan promotion of peace, any efforts to curb US armament was seen by many as de facto communist collaboration.

Pauling was monitored by the FBI and questioned twice by the Senate Internal Security Subcommittee (SISS), a committee that was very suspicious of Pauling’s peace activities, especially the petition against nuclear bomb testing. The subcommittee subpoenaed him in June 1960 and demanded to see the names of all those who had helped gather signatures for the petition in 1957 and 1958. Pauling refused to provide this information as he felt a moral obligation to protect others from the types of governmental investigation that he himself was experiencing. The group subpoenaed Pauling again in October, but when he once more refused to produce the names the group backed down and he did not suffer any legal consequences.

On October 10, 1960, the day prior to Pauling’s second hearing before the subcommittee, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat published an editorial on the proceedings titled “Glorification of Deceit.” The piece was written in the context of support having been expressed for Pauling by professors at Washington University, which is based in St. Louis. The editorial besmirched the reputations of two specific Washington professors, Edward Condon and Barry Commoner, and contained incorrect information regarding the June SISS proceedings. Its author wrote

The Senate subcommittee called Pauling to testify as to who helped him collect the petitions. Pauling contemptuously refused to testify and was cited for contempt of Congress. He appealed to the United States District Court to rid him of the contempt citation, which that court refused to do. The appeal from the lower court’s affirmation of contempt is expected to be handed down by the Supreme Court today.

In fact, while Pauling did refuse to release the names of the people who helped him to collect signatures, he was never cited for contempt of Congress.

(Globe-Democrat publisher Richard H. Amberg defended the piece by suggesting that the Washington Post had run an editorial stating that Pauling had been cited for contempt of court, and that this information had been used in composing the St. Louis paper’s editorial. However, no one was able to produce a copy of the original Washington Post text.)

The piece went on to pretty clearly imply that Pauling was, at best, not a patriot. It concluded

Much is made of the fact that Pauling is a Nobel Prize winner. That is no guarantee of anything more than proficiency in chemistry. It certainly is no guarantee of either patriotism or correctness in foreign policy. It above all does not cloak him with an immunity to defy the Senate and to decide on his own prerogative what is best for America.

A great St. Louis institution is being badly used, nor is it the first time, by a group which glorifies deceit and evasion in the outrageous guise of freedom of speech and conscience.

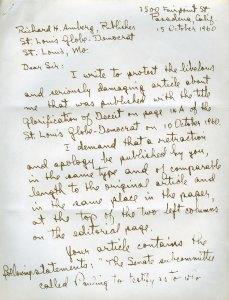

Pauling was infuriated and, on October 15, wrote to Richard H. Amberg, the Globe-Democrat’s publisher, in protest:

Your completely untrue statements have without doubt greatly damaged my reputation and impaired my integrity in the minds of your readers in the St. Louis district and of others who may have seen them in your paper or possibly in other publications where they may have been quoted from your paper…I protest against your imputation that I am lacking in patriotism, and I demand that it be retracted.

Pauling’s letter was sent along with a letter from his lawyer, A.L. Wirin, insisting that both Pauling’s letter and a retraction be published.

Not suprisingly, many others in St. Louis – in particular, a number of Washington University faculty – were outraged by the Globe-Democrat’s opinion piece. Several people wrote letters to the editor condemning the editorial, the paper was deluged with phone calls, and a protest was staged at the university. Although some of the outraged letters were published, the negative response was mostly underplayed. In particular, the protest event received little news coverage and the article’s dissenters were subsequently dismissed in later editorials.

The Globe-Democrat published Linus Pauling’s letter on October 24th but offered only a very mild retraction, so Pauling decided to sue the paper for $300,000, claiming damages to his reputation. He immediately secured the services of at least three lawyers, who pretty quickly encountered an unforeseen problem: the court involved in Pauling’s libel suit demanded that he produce the names of the people who had helped to collect signatures for the nuclear bomb test petition. This was the very information that he had worked so hard to protect during the SISS hearings. The request presented him with a moral dilemma, one spelled out in a letter that he wrote to his lawyer in December 1960.

Most of these 59 American scientists are people of such established reputation that it might be thought that no reprisals could be visited against them. However, the fact that I have suffered through being subpoenaed by the Internal Security Subcommittee and through the issuance of damaging statements about me by the Acting Chairman of the Subcommittee shows, I think, that I cannot by any means be assured that reprisals would not be visited against these scientists, despite their established reputations….The attack on me by Senator Dodd and the Internal Security Subcommittee has continued even after the hearing, and I feel that I cannot turn over names to the Subcommittee or make the names public in such a way that the subcommittee would come into possession of them.

After receiving a letter from his lawyers urging him to change his mind, Pauling replied in January 1961.

Senator Dodd did not overrule my objection and direct me to produce the names. In view of this fact, I believe that I am justified in continuing to keep these letters of transmittal confidential.

His counsel then advised him:

I am afraid that the matter becomes rather different when you are asked to produce them in a libel suit which you yourself have filed. The Court may very well say ‘You may keep the letters of transmittal confidential if you desire, but the defendant has a right to see them to make any possible defense to this suit. If, therefore, you refuse to produce them, the Court has no alternative but to dismiss your suit.’

In the meantime, the Globe-Democrat continued to publish articles attacking Pauling. In March the paper wrote an editorial titled “Pauling Rebuked” that spoke to a report that had recently been issued by SISS. The SISS publication stated that the world communist movement had applauded Pauling’s 1958 petition. The Globe-Democrat surmised

Men, like Pauling, who should know better, and the many in St. Louis and elsewhere who immediately leaped to his defense, have wittingly or unwittingly—and we believe they knew what they were doing—played the Communist game.

Barry Commoner, ca. 1960s.

Wrestling with his moral dilemma, Pauling decided to write to some of the people who had helped to circulate the bomb test petition to see how they would feel about him releasing their names in the context of his libel suit. He wrote to Barry Commoner, one of the men who helped him to formulate the idea of the petition and who collected many signatures for it. Commoner replied that he would like to know more about how the information would be used and expressed a wish to speak to Pauling about it directly over the phone. In August 1961, Pauling wrote back:

I think that it is my duty to make a decision about the letters still in my possession from American scientists who communicated the signatures of themselves and other scientists to the Appeal….Of all of the approximately 60 Americans whose letters I have, you are the one who is most closely connected with the Appeal, other than myself….Your close connection with the Appeal is of course on the public record….I think accordingly that the difficulty that you have found in deciding how to respond to my request, and have expressed in your two letters to me, provides the answer to the question that was on my mind.

Commoner replied to Pauling later that month:

I believe, as you do, that those of us publicly associated with the Appeal have a moral duty to protect from harassment the others who helped in this work….I would regard any demand for details regarding the circulation of the Appeal as a serious threat to academic freedom, and I would consider it my duty as a member of the academic community to resist such a demand….My own judgment is that I could find no justification for giving the Globe-Democrat attorneys answers which I would refuse to give the government agency. In general, I do not understand why my letter is relevant and necessary in order to establish that the Globe-Democrat made false and damaging statements about you. Further, it seems to me that the suit could – regardless of who wins it – have the effect of bringing about a violation of the principles for which you have fought so hard, and in the local circumstances it may precipitate the kind of harassment of our colleagues that is so repugnant to all of us.

While Commoner’s letter built a case against making the letters of transmittal public, another signature gatherer, Charles Coryell, did give permission for his name to be used in court and did not seem concerned about the consequences. After much thought on the matter, Pauling ultimately decided to release the names for the lawsuit.

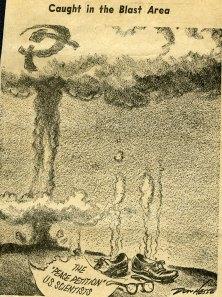

Editorial cartoon published in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 12, 1961.

Meanwhile, Pauling’s lawyers were becoming more and more concerned about how his case might fare were it to go to a jury, due mostly to the barrage of negative commentary being released about him. In a letter between two of Pauling’s representatives, A. L. Wirin wrote to John Green:

It is Dr. Pauling’s considered view that the suit should be filed. We realize fully that it may not be possible to obtain for Dr. Pauling the public vindication which he deserves, as you put it so well. But we feel that good conscience is on Dr. Pauling’s side; good conscience should prevail in the courts; and Dr. Pauling is willing to take the chance that it may not.

Amidst this backdrop, the Globe-Democrat continued to publish opinion pieces that chipped away at Pauling’s standing. On September 12, 1961, the paper released an editorial titled “No Thunder on the Left,” which pointed out that

The Soviet Union has violated its nuclear test pledge openly now – for almost two weeks….We have waited, though without baited breath, for bitter protest from the Pauling galaxy of scientists who raised such a furor in America, demanding absolute ban against nuclear tests of all kinds….[Pauling] seemed immensely more concerned to get the United States and other free countries to prohibit nuclear tests – with no mention made in his proposals for inspection or controls

The piece also reiterated Pauling’s status as portrayed in the March SISS report: “A subcommittee of the Senate last March found that Dr. Pauling had ‘displayed a significant pro-Soviet bias.'”

The editorial further frustrated and angered Pauling, in part because inspection of testing programs in other countries was clearly mentioned in the 1958 petition. Pauling also regularly spoke out against testing in all of the era’s nuclear nations.

By this point, Pauling’s support system was starting to erode. Barry Commoner, in particular, now found himself in active opposition to Pauling’s lawsuit. Though he remained Pauling’s friend and certainly was in line with most of his activism, he was worried about Pauling’s decision to turn over the names of those who circulated the petition. His hope was that Pauling would drop the lawsuit to mitigate further risk to his and others’ reputations, especially in St. Louis.

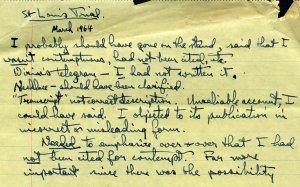

Pauling’s notes on the Globe-Democrat jury trial, following its conclusion. March 1964.

In March 1964, Pauling’s libel suit faced a jury trial in St. Louis and was defeated. Pauling filed many libel suits in the early 1960s and most of them were lost due to an important United States Supreme Court ruling, New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, that established a higher standard of proof for libeling public figures. Interestingly, Pauling lost the Globe-Democrat case before this new paradigm had been established. It may well be that Pauling’s lawyers’ fears had been justified; that his case had gone down in flames largely because of the negative public sentiment engendered by its defendant, the Globe-Democrat.

Embattled and in a stubborn frame of mind, Pauling decided to appeal for a re-trial, but the following year his request was rejected. His lawyers appealed a second time and in 1966 they received an opinion from the United States Court of Appeals denying the claim, based on the New York Times ruling. Pauling then filed a writ of certiorari, but that too was dismissed in 1967. And so it was that the Globe-Democrat debacle finally came to a conclusion, nearly seven years after it began.