Never Trust Your Own Bad Press

Mozart in his later years (nndb.com)

We take it for granted that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was an overindulged, childlike, and devil-may-care fellow who loved good wine and good jokes (but not so good women). That he was also a supremely gifted artist is a matter of historical fact.

Despite the obviously bad press he’s gotten throughout the years, there’s been no argument whatsoever that Mozart, above all the composers of the Classical period, was perfectly capable of writing in just about every conceivable form. From piano pieces, string quartets, octets, and concertos, to symphonies, sonatas, solo works for individual instruments, cantatas, motets, songs for soprano, dozens of operas (both comic and tragic), and even lofty church music.

In fact, his varied output of sacred works has been described as miraculous, melodious, and this side of heaven – in more ways than you might imagine. One of his absolute best came near the very end of his life: the unfinished yet spiritually uplifting Requiem in D Minor from 1791.

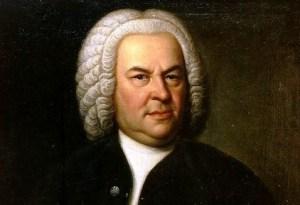

This fabulous choral and instrumental piece, “fueled by a dark and furious energy,” has been deemed by most musicologists as rivaling, if not altogether surpassing, the finest church music that issued forth from the pen of Johann Sebastian Bach. That’s high praise indeed, considering that Bach was one of the most prolific musicians who ever lived, with two (count ‘em) two wives to his name, as well as a boatload of talented offspring.

How the Requiem came to be written has been a matter of conjecture for a number of years. Believe it or not, playwright Peter Shaffer was right on the mark (well, almost) when, in the play and movie Amadeus, a mysterious masked stranger comes to Mozart’s door to commission a mass for the dead. Little does Wolfie know that the man behind the mask, and under the three-cornered hat, is his arch-rival Salieri; and the mass in question is for Mozart himself!

As patently melodramatic as this may have all sounded, there is some basis in fact. The reality of the situation was this: an eccentric aristocrat named Franz von Welsegg had the nasty habit of commissioning others to write music that he would later claim as his own. Such was the case with the Requiem. According to accounts of the time (some of which are purely speculative), Welsegg, through several intermediaries, gave Mozart a partial down payment to begin work on the project, only to have Mozart die a short while later.

Welsegg never fulfilled the remainder of his contract and was all set to claim the mass as his personal property. Fortunately for posterity, Mozart’s widow Constanze was able to deter this miscreant from making off with her late husband’s work by having the mass, or what little of it there was, a) completed by others, notably Franz Xaver Süssmayr and Joseph von Eybler; and b) performed in a public concert. Unlike the ditzy movie version, the real Frau Mozart knew a thing or two about how to outsmart others!

You can judge the beauty and power of this work for yourself in the following clip from a live Vienna Philharmonic concert, conducted by maestro Herbert von Karajan: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ia8ceqIDSJw

Johann Sebastian Bach

While J.S. Bach succeeded in accomplishing his many labors by living to a then-ripe old age of 65, poor Mozart suffered an early demise at 35. We should bear this in mind the next time someone attempts to compare these two artists’ gifts. Dare we ask who was the greater of the two? That’s a matter of personal taste and opinion. I’m of the conviction that both men were equally great, but in their own individual way. Of one thing we are certain: Mozart wrote operas – many of them forming the cornerstone of the standard repertory – whereas Bach did not, which is why Bach was not included in our fabulous foursome.

You’re Not Getting Older, You’re Getting Better

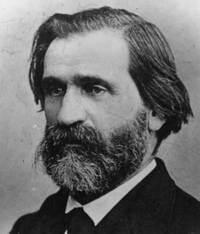

Another long lived member of the Fab Four of Opera was the Italian-born Giuseppe Verdi (1813 – 1901). As serious and sullen in his outlook on life as Mozart was sunny and disarming, the mature maestro Verdi, who regularly sported a full beard that gave him a suitably brooding countenance, had all the darkness of character implicit in Shaffer’s play that its cackling protagonist Wolfie so sorely lacked.

Giuseppe Verdi (longisland.about.com)

Due to an outbreak of typhoid, Verdi suffered the loss of his entire family early on, to include his wife and two young children. Yet, for such a melancholy gentleman Verdi left the public with a most imposing list of stage triumphs. Even a partial litany of his accomplishments would make any operagoer’s head spin: Nabucco, Ernani, Macbeth, Luisa Miller, Rigoletto, La Traviata, Il Trovatore, Un Ballo in Maschera, La Forza del Destino, I Vespri Siciliani, Don Carlo, Aida, Otello. The list seems endless.

His finished product numbered over two-dozen works, several of which were thoroughly reworked or refurbished several times during his lifetime. That was Verdi for you: the man just kept at it, until he finally got the thing right. No wonder he’s been hailed the world over as one of the few composers around who grew better at his task the older he got.

Consider if you will that Verdi lived to the age of 88. Consider, too, that he was a mere lad of 26 when he composed his first opera, the nearly forgotten Oberto; and that his last stage-work, the comic opera Falstaff (based on Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor and parts of Henry IV), was written when he was nearing 80. What we’re talking about, then, is a career that spanned more than half a century. Imagine how many operatic hits Herr Mozart might have completed had he lived as long as Verdi! Too many notes, indeed!

Born on October 13, 1813, in the provincial town of Le Roncole, in the north of Italy, young Verdi was not blessed with financially well-to-do parents. Quite the opposite: he was considered a pauper by the rigid social standards of the time, yet his talent for music and grasp of the fundamentals of his art were plainly evident from an early age.

I can reasonably assure you that once heard, a Verdi melody will not soon be forgotten. Think of the Drinking Song from La Traviata, or better yet the aria “La donna é mobile” from Rigoletto. Here’s a sample, sung for us by Juan Diego Florez: http://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=juan%20diego%20florez%20la%20donna%20e%20mobile&source=web&cd=4&cad=rja&ved=0CDsQtwIwAw&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.youtube.com%2Fwatch%3Fv%3DeHcjAXmDHSs&ei=KxXzUeqNKJLy8ASU34GYDA&usg=AFQjCNGLnEim6w-CFLxsBbTa5T09Z3ahww

The case for “La donna é mobile” is an especially compelling one.

Juan Diego Florez (musicalcriticism.com)

The story goes that the tenor at the opera’s premiere was desperate for a third act showstopper. Verdi, that wise old man of the theater, knew perfectly well he had a hit tune on his hands. To release that tune prematurely into the music world, however, would have spelled doom for his piece. Why, every organ-grinder in town would have played the catchy theme before it had a chance to be heard in context, thus losing the dramatic impact its composer had originally intended.

Consequently, Verdi refused to give the tenor the music for the number until just before curtain time. Heard in its proper setting, the aria was the hit of the show! This is only one example from among many of the composer’s incredible farsightedness with regard to his own melodic output.

Here’s another example of his melodic output: it’s one of Verdi’s most potent scenes for tenor, the aria, “Ah, si ben mio,” followed by the fiery cabaletta “Di quella pira” (“The blaze from that funeral pyre”), from the opera Il Trovatore (The Troubadour), a tour de force if ever there was one. It will be sung by one my favorite artists, tenor Luciano Pavarotti, accompanied by soprano Joan Sutherland.

As a side note, Verdi did not write the two famous high C’s that conclude this piece. Those were added some time later by a lead singer who really wanted to show off his talents. With that said, this is as good an opportunity as any for Pavarotti to show off his talents. Let’s see if he can pass the tenor acid test:

Joan Sutherland & Luciano Pavarotti (images)

(End of Part Two — To be continued…)

Copyright © 2013 by Josmar F. Lopes