Sleeve cap ease – it depends. That was the gist of my post on how to draft a sleeve sloper and I stand by what I wrote. I apologize if this the following paragraph is redundant but it’s important that readers who have not read the sleeve sloper post understand my reasoning. I also want to be consistent. In the post, I wrote that there are many factors that affect the fit of a sleeve, including sleeve cap height, sleeve cap width, and the relationship of the front sleeve cap to the back sleeve cap. But the most important factor that affects the fit of a sleeve is sleeve cap ease. Sleeve cap ease is the extra amount (or length) that is given to the sleeve cap so that it fits over and around the shoulder joint. Sleeve cap ease also effects sleeve cap height, sleeve cap width, and the shapes of the front and back sleeve caps (example: increasing the amount of sleeve cap ease will and/or increase sleeve cap height and sleeve cap width). The secret to sleeve cap ease is that it depends. Another way to say this is that the correct amount of sleeve cap ease depends on the fabric and the silhouette of a particular garment. This is where textbooks go wrong. Many textbooks advise that all sleeve caps should measure between 1” and 1 1/2” more than the sum of the front and back armholes. In some cases, this amount of sleeve cap ease works (tailored jackets) but in most cases, it does not. For the two and a half years I worked in the technical design department, many of the garments that passed through my hands had a sleeve cap that only measured ½” more than the sum of the front/back armholes. It worked and this is because the majority of the garments were knit and styles were basic set in sleeves (on a knit t-shirt, the sleeve cap doesn’t “lift” as it does in a woven – it lays close to the body, stretches with the shoulder, and therefore doesn’t need as much ease). After working on many sleeves during my tech days, I defined my own rule – sleeve cap ease depends. Some sleeves will require little ease (1/2″-3/4″ for knits) while some sleeves require a lot of ease (1 1/2″-1 1/2″ for tailored jackets) and this is because some fabrics ease easily (knits) while others do not (suedes/leather) and some silhouettes require more ease (tailored jackets) while others do not (drop shoulder). And here is an example to prove my rule.

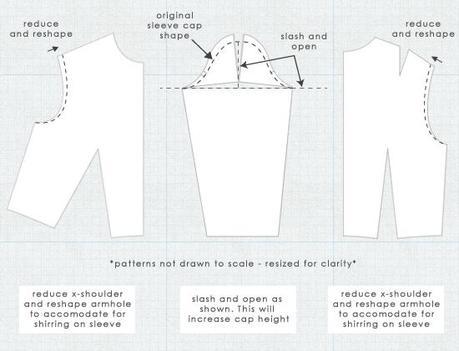

On a basic knit tee with a set-in sleeve, only ½” sleeve cap ease is needed. But what if the sleeve cap is shirred and both the sleeve and the body were woven? Obviously, ½” sleeve cap ease is too little. On such a sleeve, I would slash and open my cap as shown in the diagram and add 1 ½” of ease on either side of shoulder notch (3” of shirring is a good starting point for shirring – not too much, not too little). The act of slashing and opening would increase sleeve cap height and under different circumstances (example: slashing and opening the bottom opening/hem of a pencil skirt to create a flared skirt), I would true the pattern to maintain the original length. But with a sleeve cap, I want that extra length. If the sleeve cap is trued and the extra sleeve cap height was eliminated, there wouldn’t be enough “poof” to the cap. Make sense? Another pattern alteration I would make would be to reduce the across shoulders as shown in diagram. If ¼” was added to sleeve cap height, then I would reduce across shoulders by ¼” on either shoulder (for a total of ½” x-shoulder reduction). Alterations to the sleeves always effect armholes – remember that.

Now do you see why sleeve cap ease depends?