The cartoon campaign that made Thomas Nast the most recognizable cartoonist in the nation during the late nineteenth century was his campaign in Harper’s Weekly that brought down William Tweed and Tammany Hall in 1871. In it, Nast drew cartoons critical of the kleptocracy that was running (and ruining) New York City. Because Tammany Hall was a political machine bent on keeping itself in power and enriching its supporters, there were many people and institutions that were supposed to keep that power in check but did not because they were caught up in the racket like most of the power structure in the city.

That campaign is well-documented. It reaches its climax with the famous Tammany Tiger mauling Columbia. What made it famous is the fact that it worked. Harper Brothers, the publishing house that produced Harper’s Weekly in the 1870s, was more national than local so did not have to kowtow to the Hall and bend to its will. Although Harper Brothers was threatened by the machine,it did not stop the campaign.

Other cartoon campaigns have earned success as well, but they are less well-known. One such campaign was waged by Joseph Pulitzer, the new owner of a newspaper called The New York World. Pulitzer bought the struggling publication in 1883 and by 1884 went on a journalistic warpath to defeat James Blaine in the presidential election. The cartoonist Pulitzer employed to illustrate the campaign was Walt McDougall. According to Sidney Kobre, author of The Yellow Press and Gilded Age of Journalism (Florida State University), because Blaine lost the electors in New York, he lost the election and it was largely because of the Pulitzer/McDougall/ World campaign.

The effort to defeat Blaine (notice that I do not use the more positive reference that the effort was to help Grover Cleveland win—that is because it really did not matter who the Democrat was in the race, the objective was to defeat the Republican) began in June soon after the Republican Convention ended. By September the illustrations were in full attack mode. Not only that, they were published on page 1, above the fold and centered under the masthead. Readers who were choosing a newspaper at newsstands in New York were attracted to the cartoons, and because of them, the struggling World became the highest circulation newspaper in New York—on the days that it ran a cartoon (mainly Saturdays and Sundays).

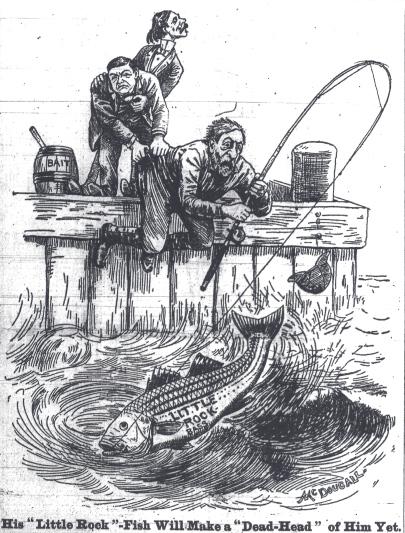

As with most negative campaigns, The World began with a lingering scandal from 1876 in which Blaine was accused of taking a bribe in the form of selling bonds to the Union Pacific Railroad for the Little Rock and Ft. Smith Railroad at a price greater than their value. He was the Speaker of the House at the time. The following cartoon from September 14, 1884 depicts Blaine hooking a Little Rock bass and being “pulled in” by the fish while Union Pacific executives rescue him.

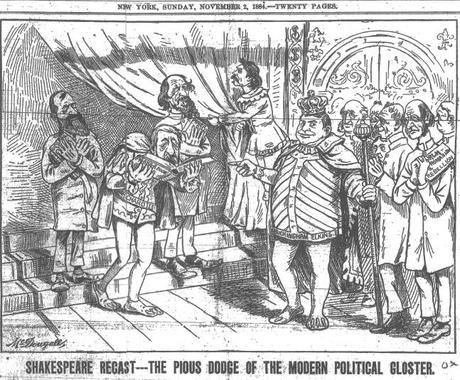

In a cartoon of November 2, 1884, Blaine is depicted as Gloucester (Gloster) in Shakespeare’s Richard III. In the play, Gloucester is accused of “weeping millstones” at a death. In this “scene,” Blaine appears to be weeping while reading a prayer book. Incidentally, McDougall later depicts Blaine in a dream from Richard III at his “Bosworth Field” (Waterloo). Both the prayer book and Richard III are recurring themes in this campaign.

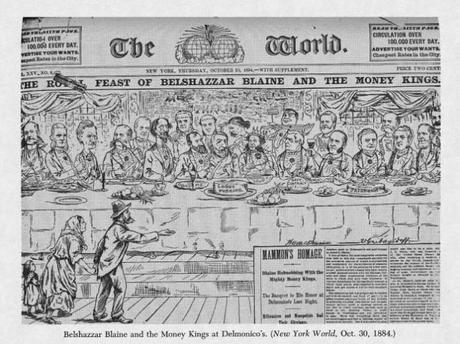

Unlike Thomas Nast who ran the best cartoon of his campaign as the final cartoon before the election, McDougall ran his best cartoon of the campaign on October 30, 1884. “The Royal Feast of Belshazzar Blaine and the Money Kings” depicts James Blaine front and center with the wealthiest of his supporters at Delmonico’s Steak House in New York. In front of the table are the depictions of a poor father, mother, and child who are ignored as they beg for any food that can be spared. A close inspection of the cartoon reveals the various serving dishes which are labeled “Monopoly Pudding,” “Gould Pie,” “Navy Contract,” and “Patronage.” The various celebrities were recognizable to New York readers in 1884. They include, John Aspinwall, J. F. Dillon, William Evarts, Levi Morton, Scott Sloan, Cyrus Field, David Dows, Jay Gould, Blaine, Whitelaw Reid, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Stephen Elkins, John Roach, William Dowd, Chauncey Depew, Noah Davis, Rufus Hatch, Jesse Seligman, Russell Sage, and Anson McCook. Many of them are labeled on their napkins or on their foreheads (a rhetorical device of 19th century cartoonists that, fortunately, is no longer in use).

The beauty of this cartoon is that a feast of this sort actually did take place shortly before the election, and it was reported as an exclusive and extravagant affair attended by only the most celebrated of New Yorkers–and beyond. By putting this on the cover of The World shortly before the election, it sealed Blaine’s fate–oh, and Grover Cleveland’s victory in New York, and consequently, the entire election. The lesson that is to be gleaned from this cartoon is that a candidate should not thank his/her supporters before the election is over.

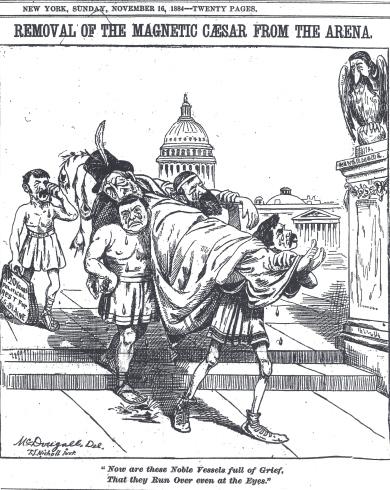

In both the Nast and the McDougall campaigns, the negative cartoons did not end with the defeat of the bad guy (as with all good stories this is a conflict between good and evil). On November 16, The World printed “Removal of the Magnetic Caesar from the Arena,” a cartoon depicting Roman soldiers carrying a vanquished James Blaine from the Capitol. In a nod to E. A. Poe, a vulture observes the action from a pedestal labeled “Nevermore.” The caption at the bottom contains ekphrasis that is paraphrased from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. Trailing the weeping warriors is William Walter Phelps, a congressman from New York, carrying baggage that states, “20 years Political rest for J. G. Blaine.” Blaine never ran for president again, and died in 1890 while serving as Secretary of State under Benjamin Harrison.

On December 15, 1884, The World reported that it outsold all other newspapers in New York on Sundays, the days on which it ran political cartoons (they ran on other days as well, but always on Sunday until the election). There is no doubt that the cartoons on page 1 were the main reason why it sold so well.

In the election of 1884, there were a total of 401 electors. Therefore, the winning candidate had to garner 201 votes to win. New York had 36 electors, the most of any state at the time. And while it was not necessary to win New York to win most presidential races, in this one it was. Without New York’s 36 votes, the total was Blaine 182 and Cleveland 183. The difference in the popular vote in New York was that Cleveland won 1,047 more votes than Blaine of the 1,167,003 votes cast (a difference of less than .09%). That is what led Sidney Kobre to conclude that the presidential race of 1884 was probably won because of The World’s cartoon campaign.