Costa-Gavras is an equal-opportunity antiauthoritarian. After Z (1969) attacked Greece's slide into reactionary dictatorship, he excoriated Communist repression in The Confession (1970). Then there's State of Siege (1972), fictionalizing the murder of CIA operative Dan Mitrone. It's a topical drama that hasn't dated, exposing hard truths about American foreign policy.

Costa-Gavras is an equal-opportunity antiauthoritarian. After Z (1969) attacked Greece's slide into reactionary dictatorship, he excoriated Communist repression in The Confession (1970). Then there's State of Siege (1972), fictionalizing the murder of CIA operative Dan Mitrone. It's a topical drama that hasn't dated, exposing hard truths about American foreign policy. In Uruguay, the revolutionary Tupamaros kidnap and execute American citizen Phillip Santore (Yves Montand). He's lionized as an American hero, his death an atrocity; yet as a bureaucrat with USAID, how did he deserve such attention? Flashbacks depict Santore as America's imperial fixer, helping overthrow leftist governments in Brazil and the Dominican Republic before moving to Uruguay. Under his guidance, Uruguayan authorities unleash death squads who kidnap, torture and murder their exponents indiscriminately.

Costa-Gavras enlists Franco Solinas, screenwriter for The Battle of Algiers, which explains the focus on urban warfare and enhanced interrogation. (Siege also repeats Algiers' device of playing revolutionary communiques over scenes of repression.) The Tupamaros are chic hustlers in trench coats and ponchos, chirping that their robberies are "expropriation" and voting on their hostages' fate. Despite their amateurish methods (hijacking dozens of cars for a kidnapping), they're well-organized enough to threaten Uruguay's government.

State of Siege occasionally recaptures Z's grotesque humor: the blustering ministers, policemen smashing courtyard speakers blaring revolutionary ballads. But the anger overwhelms humor, rather than complementing it. We're treated to graphic torture sessions (electrodes to genitals, yikes!) and wholesale massacres of dissidents, capped by a student radical's assassination in broad daylight. By kidnapping Santore, the Tupamaros expose a rotten nexus of Uruguyan fascists and foreign manipulators.

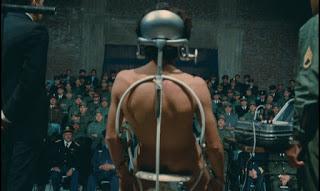

But State of Siege emphasizes that Uruguay's oppression isn't homegrown. America uses aide organizations to smuggle military advisers into Latin America, dominating regional infrastructure while cataloguing natural resources. Government meetings are controlled by American diplomats and corporation heads. One scene depicts the School of the Americans, where dictators in training learn about torture. If Solinas leans towards Marxist dialectic, the message is sound. Under the guise of anticommunism, Cold War America encouraged violence and repression throughout the Third World.

But State of Siege emphasizes that Uruguay's oppression isn't homegrown. America uses aide organizations to smuggle military advisers into Latin America, dominating regional infrastructure while cataloguing natural resources. Government meetings are controlled by American diplomats and corporation heads. One scene depicts the School of the Americans, where dictators in training learn about torture. If Solinas leans towards Marxist dialectic, the message is sound. Under the guise of anticommunism, Cold War America encouraged violence and repression throughout the Third World.Costa-Gavras provides striking direction, relishing long takes that show Montevideo reacting to police crackdown. From the opening, panning across bare mountains to the clogged cityscape, to the tense, intricate kidnappings, every set piece plays with clockwork efficiency. Pierre William-Glenn photographs exteriors with a striking bluish tinge that gives an air of unreality, contrasting with the city's grotesque modern style. Ironically, most of State of Siege was filmed in Chile, months before Pinochet's coup d'état.

Yves Montand he sputters anticommunist platitudes and implausible denials with weary resignation, suggesting an amoral professional rather than fanatical oppressor. It's a brilliant subversion of his previous Costa-Gavras roles: a man of integrity, playing for the wrong team. Renato Salvatori (Burn!) plays a credibly venal bureaucrat moonlighting as an assassin. German actor O.E. Hasse (Decision Before Dawn) plays an intrepid journalist who pokes holes in the official story.

Today, only the most naïve could find State of Siege shocking. In the '70s, Americans were just waking up to their country's Cold War moral compromises. The countries on their receiving end, of course, knew all along.