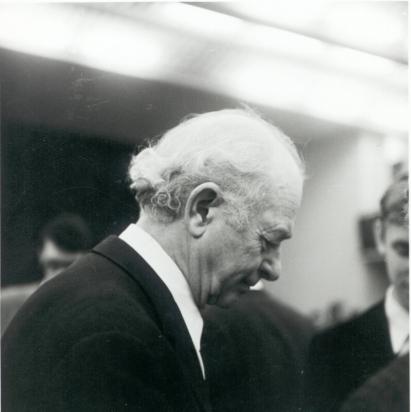

Corliss Lamont

[Ed Note: This is part 2 of 7 in our series focusing on Linus Pauling’s activism against the Vietnam War. This is also the 600th post to be released on the Pauling Blog. We thank you for your continued readership.]

“As individuals who believe that the only security for America lies in world peace, we wish to ask you why at present the United States is sending its Army, Navy and Air Force to bring death and bloodshed to South Vietnam, a small Asian country approximately 10,000 miles from our Pacific Coast.”

-“An Open Letter to President John F. Kennedy Against U.S. Military Intervention in South Vietnam,” April 11, 1962.

In spring 1962, Linus Pauling was in communication with Corliss Lamont, a philosopher and the director of the American Civil Liberties Union, who was organizing an open letter to President Kennedy (which Pauling ultimately signed) opposing military action in Vietnam. Lamont had written to Pauling share the details of his own correspondence with McGeorge Bundy, the U.S. National Security Advisor. Bundy was highly critical of Lamont’s open letter and had provided documents intended to both enlighten Lamont and dissuade him from taking a strong stance against the U.S. position.

The documents supported the argument that North Vietnam had been making a strenuous effort to conquer South Vietnam. This point of view ran in opposition to a competing reference frame that saw the conflict as being led by South Vietnamese insurgents who were waging a local civil war. Suffice it to say, Lamont remained unconvinced by Bundy’s argument, flatly stating, “I have seldom read more phony materials.”

McGeorge Bundy

In developing his position, Lamont cited Homer Bigart of the New York Times, who had reported in 1962 that only a “small trickle” of arms were actually reaching the National Liberation Front (NLF) fighters from North Vietnam, the Ho Chi Minh Trail being painfully difficult to navigate. Most NLF weapons, Lamont argued, were “crudely manufactured jungle arsenals” or had otherwise been obtained by raids on the army of the Republic of Vietnam in the south and, increasingly, by raids on American troops, whose numbers in South Vietnam continued to grow.

Additionally, Lamont argued against the American perception that the anti-Diem movement in South Vietnam was exclusively communist. In support, Lamont cited the head of the Democratic Party of South Vietnam, Nguyen Thai Binh, whose Vietnam: The Problem and a Solution supported the claim that a wide array of political groups favored unification under the government in Hanoi.

Bundy, the National Security Advisor, countered on behalf of the White House by pointing to a different New York Times report, this time filed by William Jorden. Bundy interpreted Jorden’s piece as ruling out the possibility that the NLF was a militant expression of a popular movement within South Vietnam seeking independence. Bundy offered no further specific critique or debate on the issue, stating simply that

You will not expect the President to agree with either your premises or your conclusions. For myself, I will say only that the degree of irresponsibility and inaccuracy in this letter is what I would have expected from some of the signatories, but not from all.

Responses from Vietnam to Lamont’s open letter told a different story from that being promoted by McGeorge Bundy.

In May 1962, once Lamont’s open letter had gained a global audience, a communication arrived from Le Quang. The author was a former officer of the Cao Dai Armed Forces, the military wing of a Vietnamese religious sect that acted in opposition to the Diem regime. Le Quang wrote from Paris, where he was living as a political refugee.

“Your cry of alarm has found in us an echo all the more faithful as we are more and more anxious in front of the progressive deterioration of the situation of our country,” he told Pauling. He added that it did not seem that the people of North Vietnam and the people of the United States had established just cause to go to war. Nonetheless, if the Americans continued to support the Diem government, then opposition to it in both North and South Vietnam would, by extension, constitute grounds for conflict between America and Vietnam. Le Quang implored Pauling to please help him put forward this point of view.

In September 1962, Lamont sent another letter to Pauling, this time saying that ten South Vietnamese intellectuals (two doctors and two academics as well as a pharmacist, journalist, architect, engineer and lawyer) had written to thank him for urging President Kennedy to end American involvement, and specifically calling for an end to American support of the Diem regime. The regime hierarchy, they argued, was not fairly representative of the people of South Vietnam who, by the intellectuals’ reckoning, broadly agreed with the need for unity with the north. However, the only way to know if this was indeed true, they said, was to allow the unification vote called for by the Geneva Accords in 1954.

Indeed, it seemed that a cease-fire was likely to be accomplished only if negotiations that upheld the Geneva Accords were carried out. The U.S. policy of rejecting the National Liberation Front from any such discussion was seen by American political figures as necessary, given their belief that the NLF was fundamentally an illegitimate political entity. As such, the United States would recognize only the authority of Diem, a leader whose rise to power and consolidation of control had been supported by the U.S. and whose regime was clearly receiving American military intelligence and policy guidance.

For many South Vietnamese, the U.S.’s position on the NLF appeared to be merely a means for ignoring the voice of the people in any negotiations that might occur. Especially as the war ramped up, this stance helped to crystallize South Vietnamese sentiment against the United States, possibly intensifying local support for communism and strengthening arguments against negotiation. “We firmly believe that no violence can quench a nation, however small, which is struggling for independence,” the group of Vietnamese intellectuals wrote, adding,

The history of the United States since its founding, like that of our country over the past 4,000 years, has clearly proved that the invaders and oppressors, however strong they might be, are always defeated in the end.

In March 1963, yet another letter arrived, this time addressed by seventy Vietnamese intellectuals and delivered to sixty-two Americans, including Pauling, who by now was being included directly in these international conversations. The letter’s argument was straightforward: the State of Vietnam in the south and its use of napalm and noxious chemicals (provided by the United States) constituted war crimes according to the international laws of 1922 and 1925, and the articles of the international military tribunals issued in Nuremberg and Tokyo after the Second World War.

Linus Pauling, 1963.

As the violence in Vietnam intensified, and as he became more deeply involved in these communications with the people of Vietnam, Pauling’s thinking began to shift. Whereas he had initially hoped to uncover the root cause of American involvement in Vietnam, he now saw that the reasons for the conflict, as well as his own opinions on whether or not the United States had any just cause to enter into Vietnam, were inconsequential in the face of the horrors that were transpiring.

In other words, for the purposes of facilitating an end to the violence, it no longer mattered to Pauling who was to blame. It only mattered that the fighting stop. Of course, doing so would require that both sides allow for a cease-fire and enter into negotiations.

Pauling’s task at this point became that of a would-be international arbiter; one hoping to broker the terms necessary for a mosaic of warring factions to enter into negotiations. It was a task that would consume him in the years to come.