A new Brazilian stage production, titled All of Chico Buarque’s Musicals in Ninety Minutes, is set to debut in January 2014, just in time for Chico’s 70th birthday. The musical, which features songs and numbers from the celebrated singer, songwriter, author, and playwright’s stage and screen output, will be presented in Rio de Janeiro by the award-winning team of Charles Möeller and Claudio Botelho.

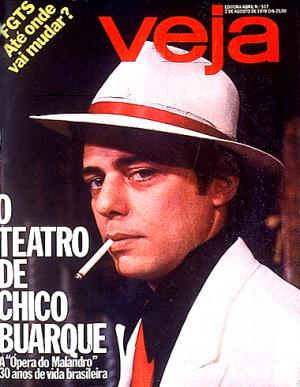

Chico Buarque, on the cover of Veja Magazine, depicted as a “malandro”

The new musical will follow the same pattern as Möeller-Botelho’s previous productions, Beatles in the Sky with Diamonds and Milton Nascimento – Nothing Will Be as Before: that is, a musical revue without text or dialogue, where each number (or potpourri of songs) links the various episodes of an artist’s career together.

“We prefer to show off the work instead of the author, that’s really what counts,” said musical director Claudio Botelho. “I detest those kinds of biographical shows,” he added, “where the artist is on his deathbed, and then gets up to relive his past accomplishments.” The revue, which highlights Chico’s songwriting skills and craftsmanship, will be small in format, with only eight actors in attendance.

This is similar to an arrangement Möeller and Botelho had prepared, back in 2006, of the singer’s Ópera do Malandro, in a stripped-down format they retitled Ópera do Malandro in Concert. A more compact version of the original play, Malandro in Concert showcased all of the work’s songs, which were interspersed with bits of dialog used, primarily, to connect the musical numbers and inform the public of the plot.

Playing to the Crowd

By way of clarification, the play known as Ópera do Malandro, or “The Street Hustler’s Opera,” Chico Buarque’s carioca twist on Brecht-Weill’s Threepenny Opera and John Gay’s The Beggar’s Opera, is set in a Rio de Janeiro of the 1940s, the heyday of strongman Gétulio Vargas’ power and influence.

As such, it’s a typically Brazilian piece – and quite a controversial one at that. I devoted several blog posts to the background of, and influences on, this groundbreaking work, which premiered back in 1978 during Brazil’s military dictatorship years (see the link, “Chico Buarque’s Modern Street Opera”: http://josmarlopes.wordpress.com/2012/10/27/chico-buarques-modern-street-opera-the-influences-on-opera-do-malandro/).

Revived in Rio, after a long hiatus, in 2003 by Charles Möeller and Claudio Botelho, the play’s songs are a mishmash of old and new styles – from samba, tango, and pop, to a riotous pastiche of the “Toreador Song” from Bizet’s Carmen, the Pilgrim’s Chorus from Wagner’s Tannhäuser, Verdi’s “La donna è mobile” from Rigoletto, and other operatic airs. In short, it’s a stand-alone stage spectacular that’s pretty-much in the popular vein.

In case you haven’t heard, a malandro is a sort of Brazilian “Goodfella,” a streetwise conman who makes his living by strictly unlawful means. For the most part, the plot of Malandro follows the same contours as that of Threepenny Opera, but with some notable exceptions. (See “What’s It All About, Max Overseas?” for a detailed overview of the story – http://josmarlopes.wordpress.com/2013/06/02/opera-do-malandro-the-street-hustlers-opera-whats-it-all-about-max-overseas/)

There was even a foreign-film version, directed in 1986 by the Mozambique-born Ruy Guerra, one of those Cinema Novo auteurs of days gone by, whose plot was drastically altered for the big screen and, as a result, does not compare favorably to the original.

The More We Talk, the More We Learn

A ninety-minute retrospective of Chico’s stage and film work sounds particularly enticing to the Brazilian singer’s many admirers. But just how such a show could possibly do justice to his extensive song production, and in the relatively brief run-time allotted to it, is a logistical nightmare most producer-directors would rather pass up. Not the Möeller-Botelho team. For them, it’s all in a day’s work: “Another opening, another show,” as Cole Porter would say.

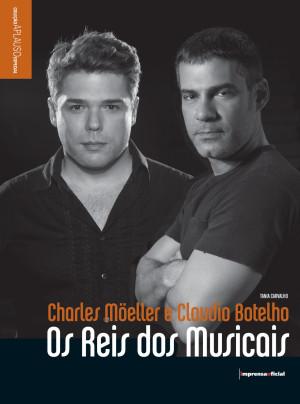

Charles Moeller & Claudio Botelho, “The Kings of Musical Theater”

A while back, I had the distinct pleasure of discussing Ópera do Malandro, as well as other aspects of the production, with musical director and adapter, Claudio Botelho, and his partner, director Charles Möeller. In addition to which, I consulted Brazilian journalist Tania Carvalho’s excellent coffee-table volume, Charles Möeller e Claudio Botelho: Os Reis dos Musicais – “The Kings of Musical Theater” (Imprensa Oficial, São Paulo, 2009), for additional insights into their mind-set and methodology.

In view of the challenges they experienced in reviving this long dormant show (among numerous other productions), what were the attractions it held for Möeller and Botelho at the time? In our talk we covered the genesis of their version of Malandro, which placed added emphasis on Chico’s incomparable songs and characters, and less on the political climate of the play’s premiere:

Josmar Lopes – It’s been ten years since you and Charles revived Ópera do Malandro. What can you tell me about your version? How did it differ from the original?

Claudio Botelho – We rewrote many of the scenes in order to make the music more combined with the dialog. The original book follows the Brecht-Weill concept, where the dialog is separated from the songs, [with the] songs usually coming at the end of each scene. We mixed music with dialog at many points and cut out about 40 percent of the dialog in order to have more musical numbers (including those from the 1986 movie version). We also created Ópera do Malandro in Concert in 2006, which has practically no dialog but still tells the story [but] with only the songs. This version includes a total of about 25 numbers.

Josmar Lopes – Who wrote the original text and numbers, and how did you and Charles get involved with the play?

Claudio Botelho – The author of the book, music, and lyrics is Chico Buarque. The show was originally produced in 1978, as it’s been published in a book, our main source to start. We were asked in 2003 to re-inaugurate the old Carlos Gomes Theater on Praça Tiradentes, which hadn’t been used or seen an orchestra or musical play occupy its space since the 1960s. Our first thought was to do Ópera do Malandro, which we had been wanting to stage for the longest time… We asked Chico directly [if we could] make a new production, and he authorized us to make any changes we needed and also include any song that he wrote for the movie version. This was discussed in a long lunch with him, Charles, and me. He only asked to see one rehearsal prior to the opening.

Josmar Lopes –Tell me a little about your specific version.

Claudio Botelho – Our version is an adaptation of his original, plus five songs from the movie version, and also a new version of the book (which was originally about four hours long!). We made many cuts in the dialog and created new introductions (i.e., spoken lines) for most of the musical numbers, as well as we included spoken lines in between the chorus of some songs… Let’s say it was a mix of everything that Chico had written for Malandro for the theater and for the cinema. This is what Chico watched and what he approved.

Josmar Lopes – What was his reaction?

Claudio Botelho – Two weeks before the opening, Chico attended one rehearsal and was very emotional about what he saw, [he] took pictures with the cast, and his lead producer, Vinicius França, decided to make a recording of the score with the new cast. This was how a long road [got] started.

Josmar Lopes – So how did the premiere go? Was it well received?

Charles Möeller – When we started working on the production, everyone was telling us, “You’ll never get this show to work, you’re crazy to even try, this in an historical landmark from the 1970s.” We went forward anyway. The play has strong political undercurrents, which we had no idea if they would be of interest to today’s audiences, and it’s extremely verbose. This troubled me, even though I loved the story. We had a closed rehearsal for our friends three days before the premiere – and it was a total fiasco.

Claudio Botelho – When the rehearsal ended, we were told it was going to be the biggest flop in Brazilian-theater history. They used words like “catastrophe” and “disaster…” People said such horrible things – and right to our faces. Charles got so sick, he couldn’t stop throwing up. But life can be very entertaining: just two days after our friends’ dire predictions, Ópera do Malandro premiered and turned out to be the biggest hit of the season – the show was supposed to last for three months, but went on to play for a solid year! From the opening in 2003 to the last performance in 2006, it ran in both Rio and São Paulo to packed houses (sold out every single night!). We then went on tour (with the whole Brazilian cast) to Portugal. The show was a huge success in Lisbon, Porto, and the Algarve in theaters of about 5,000 seats (Coliseu de Lisboa and Coliseu do Porto). Then, we went back to Portugal two other times, [but] with a different cast. The CD recording of our cast, produced by Chico’s label Biscoito Fino, was and still is a BIG HIT in the Brazilian CD market.

Josmar Lopes – I can vouch for that! It’s almost impossible to find a copy nowadays, they’re all sold out.

Charles Möeller – We became a little more “mainstream” after Ópera do Malandro debuted. Just about everyone had seen our show, Cole Porter: He Never Said He Loved Me, but it was still considered an “undergound” production, at the Arena Theater. Company was a legit Broadway outing, but more of a niche-type musical, an island in a sea of productions for the masses. But Malandro was the talk of the town. I used to walk down the street and see people dressed in T-shirts from our show. It was from that point that we took the first step in the direction of the type of show Rio de Janeiro had been unaccustomed to viewing: the type that hordes of fans would want to see over and over again.

Josmar Lopes – Have you considered loaning your production out to other producers or directors?

Claudio Botelho – In short: we have an adaptation, which is ours. No one can use our changes without our permission because that’s evidently our version (it’s never been put on stage by any other producer or director). But on the other hand, we can’t produce the show without asking Chico’s permission, again because he’s the original author of the most precious material: the songs.

Charles Möeller – Malandro gave audiences a great deal of pleasure, but for us the show was very difficult to put on; it was extremely demanding, and every day we had problems. Back then, we didn’t have the kind of structure for shows that exist today. For example, an actor would lose his voice, but there were no understudies to take over for him. Many times we had to rehearse someone at the last minute; the revolving stage platform would break down and needed to be fixed before that night’s performance. It was a never-ending cycle we had no way of preparing for. It was only in Portugal that we were able to take control of the situation and understand the dimensions of what we were doing.

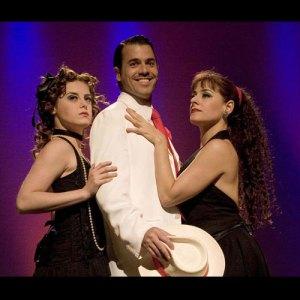

Alessandra Maestrini, Claudio Lins & Soraya Ravenle, Opera do Malandro in Concert (axion.com.br)

Josmar Lopes – With Brazil soon coming into the world’s focus, especially with the 2014 World Cup Soccer Tournament just around the corner, and the Summer Olympic Games approaching in 2016, have either of you given any thought to reviving Malandro again – possibly for the Broadway stage? If so, what changes would you anticipate making to your version?

Claudio Botelho – The thing is: we’re dealing with the Brazil of 1978 and 2003, not the Brazil we have now, where musical theater has grown to a much more professional status and structure… The original staging cost $900,000 reais [at today’s exchange rate, that’s half a million dollars]. Everything was being done for the first time. Sound, scenery, lighting, no one had done that size musical before (with the exception of Company, which had a cast of fourteen). Today, that staging would be unacceptable from a technical standpoint… That said, I think that Ópera do Malandro is a great opportunity to have Chico Buarque’s songs introduced to American audiences. He’s an idol in many countries in Europe, especially in France, and his songs from Malandro are no doubt his best work ever. We have all the orchestrations created for OUR VERSION. That’s really our material and belongs to an agreement between us and our musical arranger – Liliane Secco – and we have all the musical materials (instrumentation for twelve musicians, etc.). But we also have all the vocal score of our version written and printed.

Josmar Lopes – Have you anticipated any unforeseen situations, of the type that Charles described above?

Claudio Botelho – Well, in the middle of the production I realized that the final song of the show – which is a samba adaptation of “Mack the Knife” – was not authorized by any agency. They used it here in 1978, [but] paying only the ECAD royalties. Thank God that’s the only song with a melody by Kurt Weill, [so] it can be cut from a U.S. production if that becomes an issue. Anyway, the film version’s title is Malandro (and not Ópera do Malandro) because they needed to disguise any resemblance to Threepenny Opera. So they took out the word “opera” from everything.

Josmar Lopes – Ah, o jeitinho brasileiro! A little bending of the rules, perhaps? A typical Brazilian solution to life’s problems!

Claudio Botelho – At this point, I’d like to add a footnote, if I may: that, in my humble opinion, Brazilian actors in general were not accustomed to the rigors that musical shows demanded. It could have been a holdover from the chanchadas [an early type of musical-comedy revue], and the eternal compromises one was forced to make with the improvisational nature of such shows. But the fact remains that it was difficult to hold some actors back from wanting to “outshine” the show itself. That’s how it used to be. In the same sense, the newer generation that, in the last decade or so, has gone into the theater by way of musicals, to me seems more prepared to confront the longer runs these shows require without trying to be makeshift “co-authors.”

Charles Möeller – There’s this mistaken vision with actors who feel that, to keep their art alive, one constantly needs to invent some bit of stage business. The ones in charge of carrying out that vision are us, not the actors. I feel that the actor’s vision and talent can remain vibrant in the art of repetition, which is something Brazilian actors – in general – have trouble accepting during the course of a show’s run. And they hate to be admonished. But I admonish them just the same. At the end of each show I have one of my assistants go around and tell the actors what was different about their performance. There are actors who love this. But the majority hates it.

(End of Part One)

English translation by Josmar Lopes

Copyright © 2013 by Josmar F. Lopes (with sincere gratitude and acknowledgement to Claudio Botelho, Charles Möeller, and Tania Carvalho)