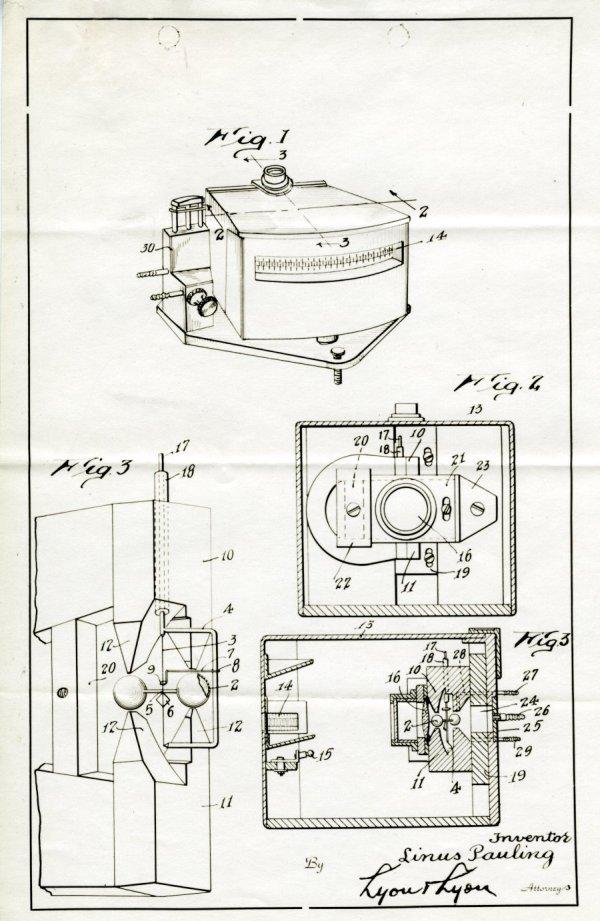

Series of diagrams of the Pauling Oxygen Meter. June 8, 1942.

The story of how Linus Pauling’s Oxygen Meter came into being has already been well documented on this blog. In our previous discussion we outlined the workings of the oxygen meter itself, the improvements that were made, and the fate of the invention in the aftermath of World War II. Today’s post will add to that story by focusing on the uniqueness of Pauling’s invention and the means by which the Oxygen Meter came to be patented.

On October 7, 1940, a contract was drawn up between Caltech and the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) for the development of the instrument. In a letter addressed to the NDRC, Pauling stated that, in view of the circumstances, and because his desire was to be of service to the country, he was willing to grant the government a non-exclusive, royalty-free license covering the entire invention throughout “the period of national emergency,” referring to World War II. He also expressed his desire that the National Defense Research Committee decide who would be given the rights to the apparatus at the end of the war.

Pauling wanted to file an application for a patent on his invention “inasmuch as it seems it will be of use in various fields other than that of national defense” – a correct supposition as it turned out. At the end of the letter, he commented that he wished to “proceed with the greatest speed in developing the instrument to the point of maximum usefulness in national defense.”

Irvin Stewart, secretary of the NDRC, wrote back and essentially told Pauling that, according to the patent clause, because he had created the invention after signing a contract with the Committee, the government was entitled to a royalty free license on the invention not only during the war, but throughout the life of the patent.

In a letter to Dr. James B. Conant of the NDRC, written February 15, 1941, Pauling next expressed a desire to patent the fundamental idea of his oxygen meter, “now that my oxygen meter will soon be put in use in other laboratories,” rather than the actual device itself. He mentioned the contract agreed to by the NDRC and Caltech, which stated that the Committee would have the sole power to determine whether or not a patent application should be filed. He also noted that “there are many uses to which the instrument might be adapted other than the original one.”

Pauling received an answer from Irvin Stewart on March 28, 1941, in which Stewart advised Pauling to apply for a patent on all of his developments that antedated the contract between the Committee and Caltech. Pauling replied that it was only after attending a meeting of the National Defense Committee in Washington, D.C. on October 3, 1940, that he initially learned of the need for an oxygen meter, and it was from this meeting that his ideas stemmed. Pauling’s desire to patent his idea was running into roadblocks, but the uniqueness of what he had devised could not be denied.

The Pauling Oxygen Meter. approx. 1940.

Pauling’s “Apparatus for determining partial pressure of oxygen in a mixture of gases” was unique for many reasons. For starters, it was both light-weight and tough. It also made use of the fact that oxygen is a strongly paramagnetic gas, which means that its magnetism does not become apparent until it is in the presence of an externally applied magnetic field. Only a few gases other than oxygen are paramagnetic, but they are less susceptible to magnetism than is oxygen. For this reason, the apparatus was valuable in determining the oxygen content of a mixture of gases, except where other paramagnetic gases such as nitric oxide, nitrogen dioxide, and chlorine dioxide were present.

Because Pauling’s device was going to be used in war, the government wanted to limit the number of people who knew of its existence. The NDRC eventually granted permission for Pauling to reveal the nature of his invention to his patent attorney in Los Angeles, provided that he did not disclose the nature of the invention to anyone else. When Mr. Richard Lyon, of Lyon and Lyon, Attorneys, requested information on the assembly of Pauling’s invention in order to better research existing inventions like it, Pauling asked Dr. Reuben E. Wood, who worked on the device with Pauling, to fill in the attorney. It is from this exchange that we learn a bit more about what made the device special.

Wood told Lyons that Pauling’s device was novel in many ways. For one, Wood could not find any other reference to the use of the magnetic susceptibility of oxygen as a means of analyzing a mixture for it. Also unique to the Pauling method were the facts that the composition of the gas sample was not altered by analysis, and that “the moving part of the device is actuated directly by the presence of the gas in the analyzing chamber.”

A similar apparatus, designed by Glenn G. Havens, had a recovery time of three minutes after being jarred or after a gas sample reading before it could be used again, while Pauling’s only needed one second. Another major difference between the two devices was that Pauling’s was portable while Havens’ was immobile and fragile.

Furthermore, Pauling’s model utilized a permanent magnet instead of an electromagnet, which meant that his magnet weighed less. Also, no source of electricity was required for the instrument to work except that required to operate a light bulb, which could be powered using a flashlight cell. All in all, Pauling’s model was more efficient, portable and dynamic than any competing instrument. Wood believed that all of these unique attributes were patentable.

Pauling filed a patent application on August 23, 1941. Having done so, he was promptly informed by the Department of Commerce of the United States Patent Office that the contents of his application “might be detrimental to the public safety of defense,” and was warned by the government to “in nowise publish or disclose the invention or any hitherto unpublished details of the disclosure of said application, but to keep the same secret.”

Later, Pauling discussed with the Office of Scientific Research and Development the procedure for obtaining a suitable manufacturer to produce his invention. The parties involved ultimately decided on Dr. Arnold O. Beckman and his organization as the likely purveyors, as they were familiar with instrument production problems through their experience in manufacturing parts for this and other technical equipment for laboratory use.

Reuben E. Wood. March 1948.

Dr. Wood, who had worked on the oxygen meter with Pauling, was also interested in patenting certain features which he had developed, so he wrote to the NDRC for permission to apply for a patent in March 1942. Important aspects which he improved upon were a “method of balancing the test body;” an improvement “which reduces the effect of temperature changes in the indication of the meter;” and “a method of selecting range of maximum sensitivity.” He later wrote to Richard Lyon enclosing four Records of Invention statements detailing his improvements on the Pauling Oxygen Meter.

However, in a letter to Captain Robert A. Lavender of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, Pauling communicated that it was not the intention of the California Institute Research Foundation to apply for patents on the inventions of Dr. J. H. Sturdivant and Dr. Reuben E. Wood. As concerned the Oxygen Meter patent, Wood was left out in the cold.

In March 1944 the Naval Research Laboratory of Washington, D.C., sent a confidential statement to the Chief of the Bureau of Ships in which it was stated that

this Laboratory has been interested in the development of an oxygen indicator suitable for service on submarines. The most satisfactory instrument has appeared to be the Pauling Oxygen Meter and a detailed study has been made of its operating characteristics, ruggedness, dependability and general efficiency with very promising results.

The letter also noted that the Pauling Oxygen Meter was found to be superior to a similar instrument – namely, the one created by Havens. The efficacy of Pauling’s invention was becoming manifest. As he himself had predicted, the device would be of use for both the war effort and in peace time.

Finally, after much brainstorming and years of collaboration, hard work and improvement, and after having been proven exceedingly useful during World War II, Pauling’s Oxygen Meter was patented on February 25, 1947, some five and a half years after the initial application was submitted.