Mind Blowing!

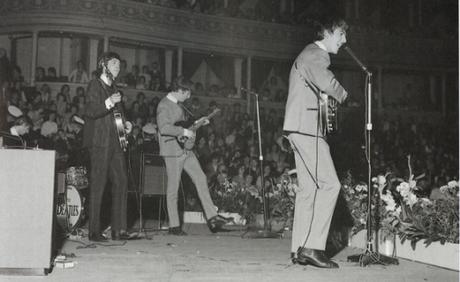

Producer George Martin surrounded by the Beatles in Abbey Road Studios, ca. 1967

Producer George Martin surrounded by the Beatles in Abbey Road Studios, ca. 1967

From the modal beauty and formality of “She’s Leaving Home,” to the purity and simplicity of “Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite,” we come to Side Two of the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. If anyone at the time of the album’s June 1967 release entertained such far-flung ideas that the Fab Four had run out of inspiration, they were in for quite a jolt.

It’s almost considered a cliché that critics and adherents alike held Sgt. Pepper up as a benchmark achievement in the pop-music field. True, the album had a considerable following among listeners and record buyers. In retrospect, many of these same folks looked at this release as not up to the standard set by the group’s earlier efforts, Rubber Soul and Revolver. Many also fell into the trap of reading way too much into its lyrics.

There may be some truth to these assertions. Be that as it may, once we get to the B Side, that illusory “drop in quality” disappears with the next two items on the list: George Harrison’s mesmerizingly hypnotic, five-minute-and-three-second “Within You, Without You,” and the rollickingly jaunty “When I’m Sixty-Four” by Paul McCartney. These two numbers are as different from one another as, say, “Eleanor Rigby” was from “Yellow Submarine.” Yet, the words and music for both “Within You, Without You” and “When I’m Sixty-Four” helped sustain the image of the Beatles as modern-day pop purveyors working at their whimsical best.

A lot has been written about the Indian-derived, sonic texture for “Within You, Without You.” There’s a quantifiable, trance-inducing aspect to it, a mystical call-to-the-spirit-world ambiance unlike anything that had come before. Harrison, known to fans as the “quiet Beatle,” was speaking out and finally coming into his own as a songwriter. “One of George’s best songs,” John Lennon maintained in the Playboy Interviews. “One of my favorites, too. He’s clear in that song. His mind and his music are clear. There is his innate talent; he brought that sound together.”

Prior to this occasion, George had tinkered with Indian music in his “Love You To” (also written as “Love You Too”) on Revolver, playing the exotic-sounding sitar on that cut, and on Lennon’s “Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)” from Rubber Soul. At the time of “Norwegian Wood,” George was far from a proficient sitar player. According to Lennon, in the Rolling Stone Interviews (1970), “it took some doing to work it in. The instrument was still unfamiliar to George, and John had thought up an accompaniment that challenged his new skill. Trying and failing repeatedly to get the version they wanted frustrated John, but Harrison kept at it, mastered the part, and it was dubbed in later.”

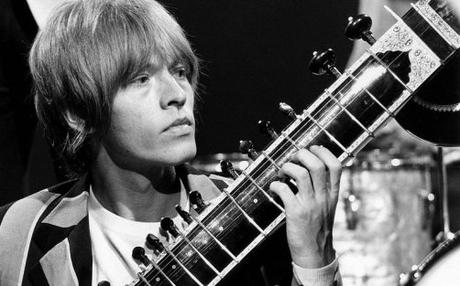

Inspired by his own studies into the music of India, in addition to Moroccan soundscapes, the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones experimented with the sitar’s capacity to hold one’s rapt attention in their classic “Paint It Black,” recorded on March 8, 1966 and released as a 7-inch single two months later — over a year before Harrison’s “Within You, Without You” began to take shape.

With the exception of boyhood chum and former roadie Neil Aspinall, George Harrison was the only Beatle present when he recorded the number. On it, he played the tamboura, along with Indian and other session musicians, who provided the dilruba, additional tamboura, the tabla, the swordmandel (a zither-like instrument, reputed to have been played by George as well), eight violins, and three cellos.

Producer George Martin worked closely with Harrison “on the scoring of it, using a string orchestra, and he brought some friends from the Indian Music Association to play special instruments. I was introduced to the dilruba, an Indian violin, in playing which a lot of sliding techniques are used. This meant that in scoring for that track I had to make the string players play very much like Indian musicians, bending the notes, and with slurs between one note and the next” (All You Need is Ears, 1979).

The origin for the piece came from a conversation George had with German-born artist and musician Klaus Voormann, the fellow responsible for the psychedelic cover art for Revolver and other albums. “Klaus had a harmonium in his house,” George recalled in The Beatles: A Celebration (1986), “which I hadn’t played before. I was doodling on it, playing to amuse myself, when ‘Within You, Without You’ started to come. The tune came initially, and then I got the first line [‘We were talking’]. It came out of what we’d been discussing that evening.”

We were talking about the space between us all

And the people who hide themselves behind a wall of illusion

Never glimpse the truth

Then it’s far too late when they pass away

We were talking about the love we all could share

When we find it to try our best to hold it there with our love

With our love, we could save the world, if they only knew

Try to realize it’s all within yourself

No one else can make the change

And to see you’re really only very small

And life flows on within you and without you

That’s deep stuff, Georgie Boy! And he was the type to deliver it, too.

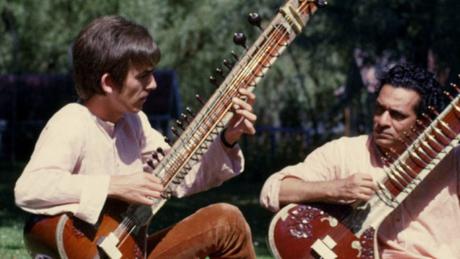

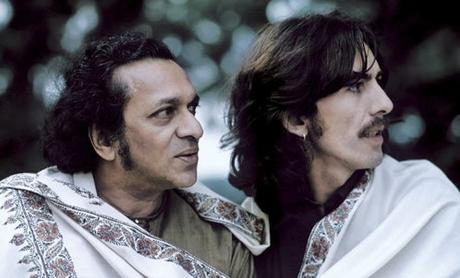

The previous fall, in September 1966, George and his wife Pattie had gone to India to study with Ravi Shankar, whom he met in June of that year. “The press had been trying to put me and him together since I used the sitar on “Norwegian Wood,” Harrison wrote in Anthology. “They started thinking: ‘A photo opportunity — a Beatle with an Indian.’ So they kept trying to put us together, and I said ‘no,’ because I knew I’d meet him under the proper circumstances, which I did…. So in September, after touring, I went to India for about six weeks … Ravi would give me lessons, and he’d also have one of his students sit with me. My hips were killing me from sitting on the floor, and so Ravi brought a yoga teacher to start showing me the physical yoga exercises.”

“It was a fantastic time,” he went on to explain. “I would go out and look at temples and go shopping. We traveled all over and eventually went up to Kashmir and stayed on a houseboat in the middle of the Himalayas. It was incredible. I’d wake up in the morning and a little Kashmiri fellow, Mr. Butt, would bring me tea and biscuits and I could hear Ravi in the next room, practicing … It was the first feeling I’d ever had of being liberated from bring a Beatle or a number… I saw all kinds of groups of people, a lot of them chanting, and it was a mixture of unbelievable things, with the Maharajah coming through the crowd on the back of an elephant, with the dust rising. It gave me a great buzz.”

Consequently, we would also expect to get a “great buzz” from listening to this seminal track, the only one written by Harrison for Sgt. Pepper. George expanded his contacts with Indian personalities, and his knowledge of their culture, when he and Pattie, along with Lennon and his wife, Cynthia, flew to New Delhi in February 1968 to study Transcendental Meditation with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

Age Before Beauty…

Following on the heels of “Within You, Without You,” “When I’m Sixty-Four” gives the appearance of being an inoffensive pop confection with an entirely innocent tone and hurdy-gurdy backdrop to match. The quartet of Paul, John, George and Ringo are back, along with session musicians on bass clarinet and two normal-sounding clarinets (that “tooty” accompaniment was composed by producer George Martin).

By all reports, Paul wrote the tune when he was about fifteen or sixteen, and to different lyrics. He claimed that the later lyrics were in honor of his father’s sixty-fourth birthday. “So many of my things, like ‘When I’m Sixty-Four’ and those, they’re tongue-in-cheek! But they get taken for real!” Paul told Playboy magazine in December 1986. “Paul says, ‘Will you love me when I’m sixty-four?’ But I say, ‘Will you still feed me when I’m sixty-four?’ That’s the tongue-in-cheek bit.” Oh, right!

Seemingly innocuous at the time, today the words have taken on a dour context, an unintentionally prophetic message about old age creeping up on people and overtaking them in the prime of life:

When I get older losing my hair

Many years from now

Will you still be sending me a valentine?

Birthday greetings, bottle of wine?

If I’d been out till quarter to three

Would you lock the door?

Will you still need me, will you still feed me

When I’m sixty-four?

You’ll be older too

And if you say the word

I could stay with you

Will you want a divorce because I can’t (ahem) “perform” in bed as I used to? Could you stand my presence, now that I’m no longer handsome and svelte as I was in my youth? Hey, you’re getting older yourself! So the shoe can be on the other foot! To save money, we could shack up together! Good questions, all! But wait! There’s more:

I could be handy mending a fuse

When your lights have gone

You can knit a sweater by the fireside

Sunday mornings go for a ride

Doing the garden, digging the weeds,

Who could ask for more?

Will you still need me, will you still feed me

When I’m sixty-four?

Here are my arguments, both pro and con, about the ravages of getting old. Why, look at all those wonderful things we can do together, the narrator tells us. We can fix the lighting or knit ourselves some clothes by that warm fireplace. How about taking a stroll in the park? Trimming the hedges, doing the wash, something, anything? Hey, please don’t abandon me! I’m still useful, even if my back aches like hell from pulling out those nasty weeds. And then, there are all those retirement perks:

Every summer we can rent a cottage

In the Isle of Wight, if it’s not too dear

We shall scrimp and save

Grandchildren on your knee

Vera, Chuck, and Dave

Oh, yeah, about those perks….

Send me a postcard, drop me a line

Stating point of view

Indicate precisely what you mean to say

Yours sincerely, wasting away

Now you’ve locked me up in a damn nursing home! On the Isle of Wight! And you’ve thrown away the key! Thanks a lot! I’m here, all by myself, “wasting away,” in body and mind — waiting for you to call, to visit me, to bring our grandkids. But so far, nothing! Nada! Zilch!!!

Give me your answer, fill in a form

Mine for evermore

Will you still need me, will you still feed me

When I’m sixty-four?

The music’s whimsy stands in barbed contrast to the lyrics’ sentiments. This modest ditty makes for a fine companion piece to the A Side’s “She’s Leaving Home,” about a girl who seemingly had everything she could want (according to her parents) — everything, that is, except love.

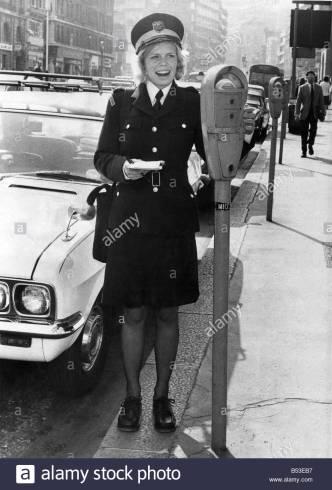

The next number, “Lovely Rita,” also written by the mop-topped Paul, is about a beautiful meter maid. What is a meter maid? In England, they’re called parking-meter attendants. In our country, a meter maid is a public functionary who works for the city or municipality. This individual is in charge of handing out tickets to car owners who park too long in the street. If the owners neglect to pay the parking fee, and the meter’s internal clock runs out (indicating the time the owner has left to move his car), a fine would be levied.

In McCartney’s view, it’s the same logic he used in conceiving “When I’m Sixty-Four”: “The idea of a parking-meter attendant’s being sexy was tongue-in-cheek at the time.” George Martin served once again as arranger. He’s credited with playing the honky-tonk piano. And three of the Beatles scrounged around Abbey Road Studio’s restrooms for the right consistency of toilet tissue in order to play the tissue paper and combs used in the song.

And Now, A Word from Our Sponsor

Moving on to “Good Morning, Good Morning,” this was a one-hundred-percent John Lennon effort. “Effort” is an extraordinarily exaggerated claim when used in connection with John’s compositional acumen. “I often sit at the piano,” he told Beatles in Their Own Words, “working at songs, with the telly on low in the background. If I’m a bit low and not getting much done then the words on the telly come through. That’s when I heard ‘Good Morning, Good Morning’….. it was a cornflakes advertisement.”

A commercial for breakfast cereal as inspiration? Well, why not, but the barnyard noises and sound effects, to include a fox hunt, bleating sheep, a mooing cow, and a cock crowing — overkill perhaps? No, not really. The chicken clucking at the end of “Good Morning, Good Morning” segues perfectly into the next to last number, a reprise (at one minute and twenty seconds) of “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.”

No horns are present, as in the opening number. Instead, a Liverpudlian brass ensemble, Sound Incorporated, was employed for “Good Morning, Good Morning.” Here, an acoustic guitar and clanging piano lead directly into the album’s pièce de résistance, a highlight to end all highlights: the Beatles’ masterly “A Day in the Life.”

Entire chapters, if not whole theses, have been devoted to this one song, so controversial and ground-breaking it became in its day and in our own time as well. Although “A Day in the Life” is the last number on the album, it was also one of the first to be recorded (after “Strawberry Fields,” “Penny Lane,” and “When I’m Sixty-Four” in December 1966). Instead of being incorporated into Sgt. Pepper, the studio decided to release “Penny Lane” and “Strawberry Fields” separately, in February 1967, as the A and B sides. After Christmas break, recording picked up in earnest on January 19 with “A Day in the Life,” and continued on until early April. Final overdubs and such lasted until its June 1 release date.

Because they were recorded early on in the process, “Penny Lane,” a nostalgic refrain based on the lads’ reminiscences of childhood in postwar Liverpool, and “Strawberry Fields,” the name of a Salvation Army home in the neighborhood where John grew up, set the path as to where Sgt. Pepper would tread, with “A Day in the Life” serving as the encore and summation of all that went before.

News reports gleaned from actual headlines figure prominently in the construction of the initial song. The first story involved the death at age 21 of the Guinness heir, Tara Browne, known to the Beatles personally. “He died in London in a car crash,” John remarked in a 1980 interview. The other story was “about four thousand potholes in the streets of Backburn, Lancashire that needed to be filled. Paul’s contribution was the beautiful little lick in the song, ‘I’d love to turn you on,’ that he’d had floating around in his head and couldn’t use. I thought it was damn good piece of work.”

It sure was. Paul’s “little lick” served as the bridge between John’s two verses. Astonishingly, the numbers combined to form a unified whole. In The Long and Winding Road: A History of the Beatles on Record, Geoff Emerick was quoted as stating, “The need for a middle section became apparent. [Paul] offered some lyrics that he was intending for another song. After discussion, they were accepted, as long as the connecting part was very rhythmic. George Martin suggested the connecting passages have a definite length.”

George Martin added that “In order to keep time, we got [roadie and friend] Mal Evans to count each bar, and on the record you can still hear his voice as he stood by the piano counting ‘one, two, three, four ….’ For a joke, Mal set an alarm clock to go off at the end of twenty-four bars, and you can hear that too. We left it in because we couldn’t get it off!”

Emerick continued: “Martin then asked what should be used in those long connecting passages. McCartney answered that he wanted a symphony orchestra to ‘freak out’ during them. Martin disagreed, but McCartney persisted. They compromised on a smaller, forty-one piece orchestra.”

In another account, it was John Lennon who suggested the use of an orchestra. “Lennon’s only instruction to George Martin was that the sound must rise up to ‘a sound like the end of the world.’ ”

Very aptly put!

Some technical sleight-of-hand was utilized throughout the recording process. You can read about the equipment that was used, the tape splices and editing loops, the laborious electronic and echo effects surrounding John’s voice, the various feeds and feedback employed — all of them fascinating for sound engineers. But all that “tech talk” tends to bog the average reader down and can be stimulating only to those interested in the subject.

For us laypeople, the lyrics are what make this piece stand out from the rest: the way John, as he speaks the words he himself wrote, delivers them in his typically cutting, matter-of-fact manner; Paul, as he introduces his contribution into the framework, imparts a passing sense of relief from the gloominess of the main story line; then John, acting out the dream sequence implied in Paul’s narration, goes off into a wordless “Ah, ah, ah, ah,” his voice rising and falling as it goes up and down the scale, interrupted at length by the rising brass section; John picks up the story about the holes in Blackburn, Lancashire; finished with his tale, he now makes the notorious crack about how we know how many holes (“assholes,” in many people’s estimation) it takes to fill snobby Albert Hall:

John:

I read the news today, oh boy

About a lucky man who made the grade

And though the news was rather sad

Well I just had to laugh

I saw a photograph

He blew his mind out in a car

He didn’t notice that the lights had changed

A crowd of people stood and stared

They’d seen his face before

But nobody was really sure if he was from the House of Lords

I saw a film today, oh boy

The English Army had just won the war

A crowd of people turned away

But I just had to look

Having read the book

I’d love to turn you on….

Paul:

Woke up, fell out of bed

Dragged a comb across my head

Found my way downstairs and drank a cup

And looking up I noticed I was late

Found my coat and grabbed my hat

Made the bus in seconds flat

Found my way upstairs and had a smoke

And somebody spoke and I went into a dream

John:

I read the news today, oh boy

4,000 holes in Blackburn, Lancashire

And though the holes were rather small

They had to count them all

Now they know how many holes it takes to fill the Albert Hall

I’d love to turn you on

The cacophonous crescendo (orchestrated, arranged and conducted by George Martin) shatters the eardrums. The noise continues to mount, rising higher and higher in pitch, louder and louder in volume. It reaches an incredible din, until the final climactic masterstroke sounds: three pianos, played by John, Paul, Ringo and Mal Evans (in some versions, by Martin; in other accounts, by George Harrison) strike the chords as loud as they can. Here’s where the facts become legend.

“The final bunched chords came from all four Beatles,” confirmed journalist and author Derek Taylor in It Was Twenty Years Ago Today, “and George Martin in the studio, playing three pianos. All of them hit the chord simultaneously, as hard as possible, with the engineer pushing the volume-input faders way down on the moment of impact. Then, as the noise gradually diminished, the faders were pushed slowly up to the top. It took forty-five seconds, and it was done three or four times, piling on a huge sound — one piano after another, all doing the same thing.”

John Lennon’s forty-five second “sound like the end of the world” idea brought to completion. And the end of one of the most innovative and significant pieces of pop-music ever created by four (no, five … or maybe more) endlessly inventive artists known collectively as the Beatles.

(End of Part Three)

To be continued….

Copyright © 2017 by Josmar F. Lopes

Advertisements