Few artists create something so wholly original that they themselves become their own genre. This is certainly true of the Marx Brothers. The family of Jewish immigrant entertainers came from the vaudeville stage tradition – which included sight gags, one-liners, and musical and dance numbers – yet the brothers remain utterly unique, even among the vast variety inherent in vaudeville. There is a certain serendipity in these geniuses developing their craft at a pivotal moment in emerging media. The Marx Brothers were able to perfectly bridge an old-fashioned stage routine with the relatively newer medium of talking film, bringing an otherwise antiquated form of entertainment into the modern age seamlessly.

Few artists create something so wholly original that they themselves become their own genre. This is certainly true of the Marx Brothers. The family of Jewish immigrant entertainers came from the vaudeville stage tradition – which included sight gags, one-liners, and musical and dance numbers – yet the brothers remain utterly unique, even among the vast variety inherent in vaudeville. There is a certain serendipity in these geniuses developing their craft at a pivotal moment in emerging media. The Marx Brothers were able to perfectly bridge an old-fashioned stage routine with the relatively newer medium of talking film, bringing an otherwise antiquated form of entertainment into the modern age seamlessly.

Part of their genius lies in their audacity, and it is the manic chaos they created that keeps their work from becoming dated. The films were made mostly in the 1930’s and 1940’s although, other than the occasional plot device, the gags are almost sui generis, entirely detached from any current outside events or influences. By creating these exaggerated characters, and playing them consistently in each film, they create their own world, which can be picked up and dropped into any time and any place. This creates a timelessness to their work and is the reason the films still play just as well today as ever. Part of this success was the fortuitous timing of talking films, but only these four brothers possessed the right kind of mad genius and grounded talent to have seized upon it so well.

The brothers were essentially born into show business, and were each musical from the start. In fact, their original act (including brother Gummo, who soon quit to fight in World War I) was primarily a musical one. Billed, in various incarnations, as The Four Nightingales or The Six Mascots, they played theaters, concert halls and other venues throughout the country as a vocal group. In response to audience behavior and events outside one particular venue Groucho began to incorporate off the cuff one-liners into their act, which immediately became more popular with audiences than the act itself. Eventually, the brothers morphed from a musical act with occasional comedy into a comedy act with occasional music. The Marx Brothers formula as we now know it was born, as was the classic line-up of Groucho, Chico, Harpo and Zeppo.

Musical numbers remained a constant element of the formula. Groucho was an accomplished guitarist, studying the instrument for most of his life. But Groucho’s contribution to the musical numbers in the films was mostly as a comedic vocalist. He did not demonstrate the flashy virtuosity of Chico’s piano or Harpo’s harp, but his numbers became centerpieces of the films and some of the most memorable moments.

Two of his best-known numbers appear as a medley in 1930’s Animal Crackers, where Groucho plays the famed Captain Geoffrey T. Spaulding.

One morning I shot an elephant in my pajamas. How he got in my pajamas I don’t know.

“Hello, I Must Be Going” and “Hooray For Captain Spaulding” create a mock grand musical number complete with company chorus that heralds the arrival and celebrates the exploits of the famed African explorer. As always, Groucho’s unique dance moves are as graceful as they are ridiculous.

This fact I emphasize with stress,

I never take a drink unless –

Somebody’s buying…

I hate a dirty joke I do

Unless it’s told by someone who -

Knows how to tell it.

The Harold Arlen and Yip Harburg penned “Lydia, the Tattooed Lady” from 1939’s At the Circus became one of Groucho’s signature songs, and one which he continued to sing for the remainder of his life at appearances. (The occasional songwriting team of Arlen and Harburg wrote several songs together, most notably “Over the Rainbow.”)

I met her at the World’s Fair in 1900 – marked down from $19.40.

The Marx Brothers were out-there even by vaudeville standards, and that flamboyance carried over into the way they performed even the “straight” musical numbers. Whether interpreting Liszt’s “Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2,” Rachmaninoff’s “Prelude in C-sharp minor,” or the “Beer Barrel Polka,” there is a certain abandon in which they played that can be traced through to the most wildly visual rock ‘n’ rollers who would emerge several decades later. When The Who’s Keith Moon rigged his drum set with explosives, detonating it after a performance on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in 1967, it seemed radical and dangerous. But Harpo had pulled off the same trick 30 years earlier in A Day At the Races with a piano – and then used the metal plate from inside the pulverized instrument as an impromptu harp.

Chico began playing the piano at an early age. Initially he faked a weak left hand and, by default, developed a strong right hand to overcompensate. Eventually he took formal lessons and learned proper technique. But this strong right hand remained evident in the style he developed. Chico glided his fingers up and down the keys effortlessly, landing on key notes he emphasized with the finger-shooting technique that would become his trademark. This style of playing, with its playful, visual panache and repetitive staccato single-note emphasis, was an obvious influence on Jerry Lee Lewis’ ferocious approach to the keyboard. Chico sometimes knocked on the wood of the piano with his fist as a sort of percussive device; a trick Jerry Lee Lewis would also employee, although Jerry Lee would attack the wood as if he were punching a heavy-bag rather than knocking on a door.

A perfect example of Chico’s style can be found in 1940’s Go West. Ever the showman, he even plays the piano with an apple that he casually lifts right out of Harpo’s mouth.

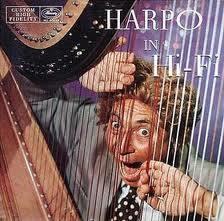

It is impossible to say that any one brother was more talented than any other. Genius, it seems, was proportioned equally among them. But when it comes to strict musicality, Harpo emerges as the true musical genius.

Harpo was entirely self-taught on the relatively obscure and cumbersome instrument. He never learned how to tune the harp properly, and so he played in unusual and technically incorrect tunings. This naturally affected his technique and approach. Unlike Chico, who seemed to be able to summon any song under the sun when at the keyboard, Harpo could only hammer out two numbers on the piano. But when he sat behind the harp, he was an endless, bottomless well of expression. And like brother Chico, Harpo’s style was ahead of its time in dynamics and sheer chutzpah.

Harpo was entirely self-taught on the relatively obscure and cumbersome instrument. He never learned how to tune the harp properly, and so he played in unusual and technically incorrect tunings. This naturally affected his technique and approach. Unlike Chico, who seemed to be able to summon any song under the sun when at the keyboard, Harpo could only hammer out two numbers on the piano. But when he sat behind the harp, he was an endless, bottomless well of expression. And like brother Chico, Harpo’s style was ahead of its time in dynamics and sheer chutzpah.

In a particularly poignant rendition of the Rogers and Hart standard “Blue Moon” from At the Circus, Harpo plucks out the pretty tune with soft legato runs, counterbalanced with dissonant, almost Ray Charles-like blue note clusters – more than a decade before Charles’ early R&B hits utilizing this sound and 22 years before the now definitive doo wop version by The Marcels – segueing into a rhythmic waltz-time bridge, with music box precision, back into an Eastern sounding – almost otherworldly – A section, capped off with modulating runs built into a circular, gentle crescendo. That’s a significant amount of musical ground to cover in less than three minutes with a simple four-chord ballad.

Harpo’s musical numbers were always a placid pause from the chaotic craziness. When accompanying Chico, it was full throttle insanity. But when alone at the harp he seemed to become transported to another place, playing with a reverence and sincerity that only helped to bolster his unorthodox approach. The brothers’ second to last film, 1946’s A Night In Casablanca, is far from their finest, but it contains one of Harpo’s greatest musical film appearances. It is a tender moment, the way Harpo sits poised ready to play, notices a feather on his sleeve, which he gently fingers and drops effortlessly into the open toe of his hobo’s shoes. When he begins to pluck the harp, there is a certain palpable shift in dimension as he transforms from the meddling clown to a serene, focused and almost majestic creator, lost in the dramatic swirls of his own sounds.

Although the brothers, obviously, were not their screwball film personas in real life, sometimes life had a way of mirroring art. In his autobiography Harpo Speaks, Harpo recounts an anecdote involving the composer Rachmaninoff. Newly arrived in Hollywood in 1931, Harpo was staying at the Garden of Allah, a series of bungalow apartments surrounding a common swimming pool, which became a transitory home to eastern transplants to Hollywood, and the site of many a salacious scandal. Harpo remained holed up in his bungalow practicing for the upcoming shoot. Rachmaninoff moved into the bungalow next door and drove Harpo to distraction with his constant pounding of the piano. Management refused to relocate the esteemed composer simply to accommodate the young actor. In response, Harpo opened every window and played the opening four bars from Rachmaninoff’s “Prelude in C-sharp minor” over and over again on the harp for two consecutive hours, until the composer finally demanded he be moved as far away from Harpo’s bungalow as possible. Only Harpo Marx could relegate the serious Russian composer into the Margaret Dumont role in one of his gags. (And he would use that very piece as the centerpiece to one of their greatest bits, from A Day At the Races, six years later – see above.)

Chico was a compulsive gambler and in later years was placed on an allowance to keep him from blowing everything he had earned. He was the first of the brothers to pass away, in 1961. Harpo released three instrumental harp records in the 1950’s for RCA Victor and Mercury, and remained a lasting and immediately recognizable cultural icon, guesting on several television shows in the 1950’s and 1960’s, including a memorable appearance on I Love Lucy. He died in 1964 of a heart attack. Groucho was arguably the most famous brother. He took the leads in the films and had a thriving career well into the middle of the 20th Century as a game show host and television personality. Groucho passed away on August 19, 1977, three days after Elvis Presley. Two larger than life icons, each so bright and brilliant it’s almost hard to believe they existed as mere humans, took their exit the same week. Zeppo, who appeared in only five movies and lived in the shadow of his more boisterous brothers, was a brilliant comic and able to imitate any of the other three flawlessly, often subbing in for them at early performances. His wife, Barbara, had an affair with Frank Sinatra and later divorced the youngest Marx brother in order to become Sinatra’s fourth and final wife. Zeppo outlived his older brothers, passing away in 1979, officially ending one of the world’s great cultural dynasties.

If one song can be considered the quintessential Marx Brothers musical number, it would have to be “Everyone Says I Love You” from 1932’s Horse Feathers. Each brother gets to showcase a bit of his unique personality while attempting to woo the stunning Thelma Todd. (Thelma Todd found success as a comedic actress in the 1930’s until her untimely and suspicious death in 1935. She owned Thelma Todd’s Roadside Rest Cafe on Pacific Coast Highway, where Raymond Chandler’s fictional detective Philip Marlowe parks his car in Farewell, My Lovely. She was found in her car in the garage of her lover’s ex-wife, above the cafe, dead from carbon monoxide poisoning. Despite disturbing evidence to the contrary, her death was ruled a suicide.)

The sequence begins with Zeppo singing the melody as the hapless romantic lead. After one time through straight, we cut to the ever-mute Harpo whistling his verse while caressing a bouquet of flowers. As the camera pulls back, we see he is serenading a horse. Next up, Chico segues into a syncopated rendition under the guise of giving voice lessons to the beautiful Ms. Todd, showcasing both his exaggerated Italian accent and his real-life penchant for using the piano to flirt with women. Groucho gets in a few one-liners (even breaking the fourth wall by addressing the audience directly; a trick Woody Allen would later incorporate into more than one film. Allen also borrowed the song and its title for his 1996 musical of the same name) before we find him on a boat crooning to the conniving Ms. Todd in his cracking, sarcastic tenor and playing a very tasty guitar part as she rows.

The song does little to demonstrate the virtuosity of the bothers’ musicianship, particularly that of Chico and Harpo. The camera never shows Chico’s fingers, which was always the focal point of his piano numbers, and Harpo doesn’t play the harp at all. But it is the entirety and cohesiveness of the sequence that makes it quintessentially Marxian. The point of the Marx Brothers isn’t so much the outrageousness of the characters, but the way in which they interact and work together as a team. The impeccable timing and instincts necessary to simply dare to engage such over-the-top personalities, let alone to compliment them, requires that inimitable sibling bond. The immigrant, hobo and obnoxious charlatan characters would each be funny on their own to some degree, but are magic when riffing off of each other. Adding the “normal” straight man character of Zeppo to the mix only helps to heighten the absurdity. The genius of the Marx Brothers is their ability to shine as individuals, even while singing the same song.

(c) 2013, Matt Powell