Animal husbandry and crop cultivation were significant advances in various 'cradles' of civilization around the globe. The banks of the Nile were fertile ground on which to grow grain, principally wheat but also barley; and that grain once harvested and milled gave flour from which to bake bread, a staple of the Egyptian diet for all classes of society. Wheat served not only as a vital foodstuff but also as a form of currency. Then, as now, farming was to a degree subject to the vagaries of changing weather patterns. However, as wheat could be stored for a long time, it actually meant that bread, such a key element of the daily diet, would continue to be available, albeit in rationed form, even when occasionally the harvests would fail - meaning that the dire picture I painted in the previous paragraph was probably an apocryphal one.

The type of wheat cultivated in Egypt was known as emmer (or faro) and was closely related to the wild wheat from which it had recently been derived. It differed from the wheat varieties that are common today in that with emmer, its heavy husk did not simply fall off in the threshing process. The spikelet had to be moistened, pounded in a mortar (but not so vigorously as to crush the grain), then dried in the sun, winnowed and sieved before it was ready to be bagged or milled into flour. Emmer is still grown traditionally in a few high and remote regions of Asia as well as on some specialty farms in the west and emmer flour is becoming more widely available again these days, but at a price (approximately three times the cost of standard plain flour).

Emmer was typically only milled to flour when it was going to be used, because the Egyptian heat would turn it rancid within a matter of hours, so the storage of grain, rather than flour, was standard. Stored grain attracts vermin, which is one reason why cats were so highly prized in Egypt, to protect granaries large and small from the scourge of rats and mice. Also, because of that heat, bread really had to be consumed fresh on the day it was made (before going hard or stale), and so of necessity the whole process of milling and baking became a just-in-time affair - literally daily bread.

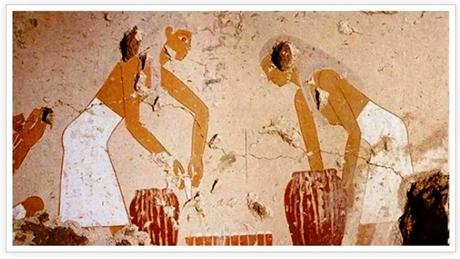

bread-making in the time of the Pharaohs

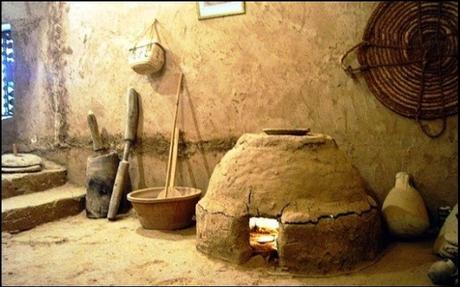

Milling the grain into flour was a small-scale and intensely physical practice, employing a saddle quern and lots of manual pressure. The quern was a concave granite stone. A handful of grains of emmer were placed in the depression of the quern and were then repeatedly rolled over backwards and forwards with a granite rolling pin until they had been crushed to a coarse flour. This process was repeated until enough flour had been produced to make the day's loaves for the household.The flour was then mixed with water into a dough and left to rise slightly (there being sufficient natural yeast in the water to allow this to happen) before being shaped into loaves and baked in a clay oven. The forms varied, judging from pictorial representations, from flat breads to traditional domed loaves to special shapes for ceremonial occasions. Milling and baking was primarily an early morning activity, but there is evidence that it was also repeated in the afternoon as well - twice daily bread; never better than when it's fresh.

a typical Egyptian clay oven, still in use today

Of course, sometimes there would be left-over bread at the end of a day; not fit to eat on the morrow as it would be too dry and stale. Yet nothing was wasted. There were two typical uses for such left-overs.One was in the making of beer, for the stale bread would be soaked and left to ferment (thanks to the yeast it contained) and the fermented liquid would eventually be strained, maybe with the addition of fruit or honey, to make a perfectly quaffable alcoholic drink - not so crazy as it sounds. I've drunk kvass (made from fermented rye-bread) in Russia and it's really very palatable.

The other was the making of Egyptian palace bread (also called Aish El-Saraya), similar to treacle tart, where the softer inner part of any left-over loaves would be sliced, soaked in honey, layered in a pan and then baked for forty minutes. Again, I've sampled this in Egypt and it is delicious in small doses, with a good cup of strong black coffee.

To round the feast out, so to speak, a humouresque take on those very left-overs, though sadly it's a triumph of neither form nor content, being a bit throw-away itself.

Palace Bred

Yesterday's loaves, too stale,

too tough to chew, still

have their uses. Nothing wastes.

Some crusts fuel the amphora,

fermenting with an odour

the cats sniff with distaste.

Softer parts are doused in nectar,

baked to make sweetmeats,

will tempt the royal tooth

as finest honeyed slices

served with foaming beer,

fit food for a fat young Pharaoh.

Thanks for reading, S ;-) Email ThisBlogThis!Share to TwitterShare to Facebook

Reactions: