-Contributed by Charity A. Smith, MA–Thanatology.

The fastest way to bring a conversation to a grinding halt, in just about any social setting, is to tell people that you have a degree in Thanatology—the psychological study of death, dying, and bereavement. And, if you really want to hear crickets, tell people you study, teach, and conduct research in the area of suicide. Occasionally, however, being a “deathy” has its perks. As National Suicide Prevention Month draws to a close, I am honored to have the opportunity to explore the topic of suicide in a fashion that is neither secretive nor sensationalized. Hopefully, rather than shutting down a conversation, this post will create one.

Among those left in the wake of suicide, the question of “Why?” is the most popular knee-jerk utterance, second only to “How?” Collectively, these questions illustrate both past and present Western attitudes toward death. How serves to satisfy our mortal (not to be confused with morbid) curiosity—this question is akin to our desire to rubber-neck when passing auto accidents; we don’t want to see and yet can’t turn away. Why, however, speaks to both our reverence toward death and our fear of the unknown. Ultimately, we are seeking an answer that sets us apart from the decedent—something that will allow us to say, “Clearly, this happened because he/she is (insert negative adjective here); this could never happen to me.”

Often regarded as the original primer on suicide, French sociologist Emile Durkheim’s text, Le Suicide (or Suicide: A Study in Sociology, as the English language version is titled) offers readers answers to a number of questions that surround this painfully enigmatic mode of death.

Although his approach to the scientific study of suicide is still highly debated (he relied on the experiences of only Catholic of Protestant participants), I admire Durkheim’s moxie. As the first several lines of the introduction to this 1897 text readily states, the topic of suicide was far less taboo during Durkheim’s era; however, it was still viewed as the result of a mental deficiency or failing inherent to the individual. Durkheim never sought to validate this “hands-off” understanding of suicide—he saw no utility in distancing himself from suicide or punitively pathologizing its decedents. Instead, the major findings presented in Le Suicide offer further credence to a concept over which we often wax poetic: no man is an island.

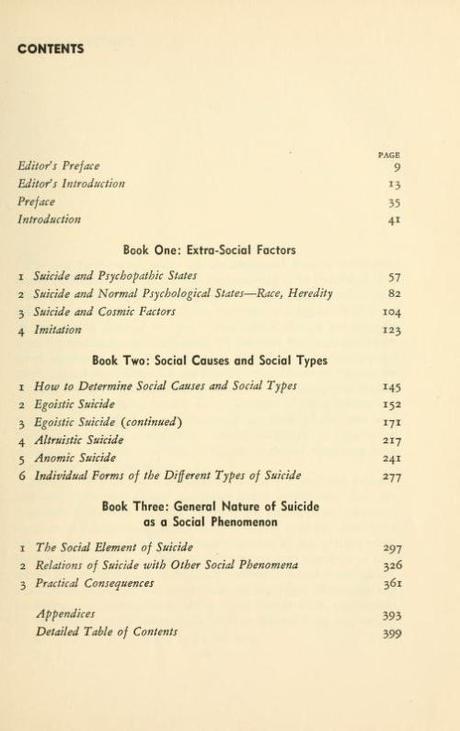

In this three-part text, Durkheim presented suicide as a sociological phenomenon, born of two intersecting concepts that collectively define our membership to society (or lack thereof): integration and regulation. This intersection marks the point at which engagement meets social control—it is the balance between our investment in society and the control we experiences as a result of society’s expectations and regulations.

Using all possible combinations of low vs. high integration and regulation, Le Suicide was the platform on which Durkheim debuted his famed sociological classifications of suicide: anomic, altruistic, fatalistic, and egoistic suicide.

Le Suicide certainly illustrates that Durkheim, the man most commonly credited with founding the discipline of sociology, was a keen observer of the human condition. More than 100 years later, his work continues to ring true, as we see the same patterns of behavior continue to ripple throughout time.

Want to check it out for yourself? The English translation of Durkheim’s On Suicide is freely available at the Internet Archive.